Former IMLR student Margaret May writes about the symposium held at the IMLR on 25 February 2019.

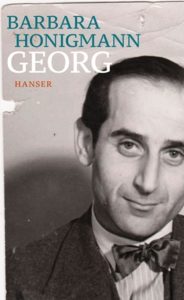

On 25 February the Institute of Modern Languages Research hosted a unique event: a symposium held in honour of writer Barbara Honigmann’s 70th birthday, in conjunction with an evening meeting between the author and her translator, Judith Köhler, in the now well-established ‘Encounters’ series, which also celebrated the publication last month of Honigmann’s latest book, Georg.

The co-organisers, Godela Weiss-Sussex (IMLR) and Robert Gillett (Queen Mary University of London), both presented aspects of their own Honigmann research and brought together ten other speakers from across Europe and the United States, whose contributions spanned an impressive range of approaches to Honigmann’s work. Several of these focused on her style and detailed aspects of her texts; others situated her work more broadly in the body of ‘German-Jewish’ literature or diasporic writing, given her position as a Jewish writer from the former GDR living in France and writing in German.

This was not the first time the IMLR had welcomed the author: two years ago she had come to read from her recent book Chronik meiner Straße (published in 2015), engaging in a wide-ranging conversation with Robert Gillett which triggered my own decision to explore her work further in my research.

The day got off to a lively start with an exciting account of Honigmann’s neglected first work, the play Das singende, springende Löweneckerchen (1977), by Martin Brady (King’s College London), which he supplemented with contemporary materials including an illegally distributed copy of the original text. It was fascinating to learn not only about the political undertones of this adaptation of a Grimms’ fairy tale with its strong, resourceful heroine, but also how much at odds Honigmann’s own accounts of the state of dramaturgy in the GDR actually were with the reality of her success with this play. This was a theme that ran through the day in explorations of the autofiction/autobiography dichotomy in her work.

Reinhard Zachau (Sewanee,Tennessee) discussed Honigmann’s ‘German-Jewish project’, comparing her experience of reconnection to her Jewish roots, as recounted in three of her autofictional texts, with W. G. Sebald’s approach in Austerlitz (2001), in which the German narrator interacts with the eponymous protagonist, who was rescued from Prague on a Kindertransport but only uncovers his suppressed memories as an adult. In both cases it becomes clear that fictionalisation of family history is one way of reworking traumas for the post-Holocaust generations.

Withold Bonner (Tampere University, Finland) examined post-memory through its relationship with photographs. Although Honigmann, unlike Sebald, does not use photographs themselves in her texts, her ambivalent descriptions of family portraits, which offer only fragmentary glimpses into past loss and destruction, often concealing more than they reveal, play a significant role in a number of her works. This offers a fruitful line of enquiry into the question of the reliability of memory – and indeed the purpose of autofiction.

The religious aspect of the ‘Jewish project’ was explored by independent scholar Malte Osterloh, who focused on its role in providing release from the burden of the past, emphasising that Honigmann did not see Judaism as the ‘right’ answer, but was constantly and consciously undermining her own hopes and expectations of redemption, except through memory and the work of studying and writing about her parents’ past.

By contrast, Rapha Hoffmann (University of Leipzig) focused more on the political aspect of this topic, relating Honigmann’s decision to leave the GDR – despite her need for connection to the German language – to the increasingly marginalised and ultimately untenable position of Jews in the socialist state, using examples from Roman von einem Kinde (1986) to illustrate his argument and making interesting links to other GDR authors.

Lauren Hansen (New College of Florida) situated Honigmann’s Eine Liebe aus Nichts (1993) within the fields of intergenerational memory, family narratives and migration literature, highlighting the theme of spatial migration not just in terms of content but as a formal, structural textual strategy. Lauren referred specifically to the arresting concept (also noted by others) of the shared, overwritten diary, seeing Honigmann’s (or her narrator’s) adoption of her father’s wartime diary (which he himself had re-used a few years later) as an attempt to reintegrate their estranged lives through the physically combined record of their experiences.

Robert Gillett explored Honigmann’s use of letters as a literary device that both suggests physical distance and represents a powerful channel for personal exchange or confessional, exculpatory writing. Speculating on the identity of ‘Josef’ in Roman von einem Kinde, with its possibly Biblical or Kafkaesque associations, he also drew attention to the relationship the epistolary form creates between author, reader and text, both heightening the sense of authenticity in the narration but also, paradoxically, questioning its implied veracity.

Godela Weiss-Sussex discussed space, time and language in a work that has often been critically dismissed, Das überirdische Licht: Rückkehr nach New York (2008), Honigmann’s episodic account of her ‘Randposition’ of distance and belonging during her period as a writer-in-residence in that city in 2005. The author/narrator’s role as an observer and student-like status, with the associated concepts of freedom, flux and mingling of past and present time, created a sense of disorientation but also provided a unique opportunity for unexpected, revealing encounters, openness to new experiences and further reflection on exile identity, as well as raising questions about multilingualism.

In the final panel, Honigmann’s engaging account of her life in Strasbourg, Chronik meiner Straße (2015), was the subject of no fewer than three contributions, albeit from very different perspectives on exile existence. Katja Garloff (Reed College, Portland, Oregon) discussed ‘diasporic place-making’, highlighting how ‘routes become roots’, how Honigmann’s imaginative narrative strategies about arrival, leaving and remaining turn spaces of transition into places of dwelling, and place-making into a form of place-claiming, by investing them with emotional significance and personal meaning.

Derek Wiebke (University of Washington-Seattle) also pursued the theme of (dis-)location, seeing the text as pushing and even extending the boundaries of ‘minor literature’. He highlighted instances of German as a vehicular language for the multicultural community living in the Rue Edel, and the numerous encounters between the personal, political, social and collective observed, experienced and described by Honigmann as a long-term resident in this street.

Among several other presentations that considered linguistic aspects of Honigmann’s texts, the approach to Chronik meiner Strasse taken by Tarek Mahmoudi (Freie Universität Berlin) mirrored my own detailed examination of the nuts and bolts of Honigmann’s carefully crafted texts, including her noteworthy use of modal particles like ‘ja’ to draw the reader in and normalise her experiences, and the particular rhythms of her sentences. Tarek also focused on recurring motifs such as the portrayal of different languages and nationalities, and specific locations of ‘in-betweenness’, in which visits to Jewish cemeteries provide a sense of historical connection that is not necessarily available elsewhere.

My own presentation analysed a chapter from this book and episodes from two earlier works, Roman von einem Kinde and the work aptly chosen as the title of this day, Damals, dann und danach (1999), in order to highlight particular linguistic features of Honigmann’s style and explore how its evolution over thirty years reflected her own journey of self-discovery.

Our enjoyment of the day was immensely heightened by Barbara Honigmann’s presence in the evening, when she read from and discussed her new book about her father, Georg, with translator Judith Köhler, in a public event sponsored by the Keith Spalding Trust. Her work seems to me to invite us to read it aloud, and it was particularly satisfying to hear this in the author’s own voice. Despite the apparent simplicity of the text, Judith had identified numerous pitfalls for the translator, which were the subject of a lively exchange with the audience as well; for instance, how much historical and German literary or local knowledge can one assume from the intended readership, and, in an English translation, how does one, right from the outset, convey all the nuances implicit in Georg Honigmann’s own use of English? In other words, how important is the translator as a cultural communicator? This conversation allowed us to pick up on our earlier discussion of particular, possibly untranslatable, linguistic features of Honigmann’s style.

Throughout this enriching day echoes of other authors – whether stylistically or thematically – were constantly noted, ranging from Kleist to Kafka, Georges Perec to Mascha Kaléko, or Hans (Chaim) Noll to Olga Grjasnowa. One thing emerged clearly from our discussions: academic interest in Barbara Honigmann’s work continues unabated across continental borders. No doubt her latest book will soon also be dissected according to our various fields of interest, but that is because her writing remains so relevant to questions of identity, belonging, migration and much more. Many thanks to Godela and Robert for convening such a rewarding celebratory event.

Margaret May

What a clear and gripping account of the proceedings of the day. Sadly I couldn’t attend, but this made up for a lot!

Thank you Margaret.