Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Future Directions in Modern Languages: Action Points

Charles Burdett, Director of the Institute of Modern Languages Research, discusses the recent symposium held on 25 February 2022 and issues that the event raised.

The question at the heart of the workshop on 25 February 2022 (Future Directions in Modern Languages) that was organised by the IMLR together with AULC, the UCML, and Bilingualism Matters was how the disciplinary area, broadly defined as Modern Languages, can develop to ensure its relevance and purpose. The importance of thinking about future challenges was foregrounded at the beginning of the event with the presentation of the work of the AHRC Future of Language Research Fellows. This was followed by presentations from researchers of Bilingualism Matters on how thinking concerning ‘community’ languages can advance decolonising approaches to the study of language and culture. The latter part of the day focussed on how the work of the four OWRI projects can be integrated within the subject area and inform developments more generally.

Many questions concerning the future shape of the disciplinary area were raised by the conference and all of these questions require a great deal of further strategic thought and engagement. One can, nevertheless, point easily to three issues that were present in all discussions. The first is how we can successfully move beyond a distinction between ‘modern’ and ‘community’ languages. The stratification of language learning is increasingly difficult to justify and serves no one’s interests. It might well, therefore, be a good idea to dispense with the adjective ‘modern’ and to seek to construct a broad, but nevertheless definable, subject area that has different emphases and inflections, but which is connected by the integrated study of language, culture, and society; that is grounded in the multilingual and multicultural realities that we all inhabit; and in which there is a strong emphasis on cultural and linguistic mobility.

The second issue that all speakers addressed was the necessity of intense, joined-up, and inclusive thinking concerning the teaching of languages and cultures. If we think about language teaching as an important element in the way in which we expand the nature of our contact with societies around the world, then it is clearly important that what is taught in schools is strongly connected with the subject area as it is understood and practiced in Higher Education. Innovative approaches to teaching, to the interface with creative practice, and to inclusivity need to be shared across the education sector as a whole.

The third issue concerns the need to demonstrate the relevance and applicability of the analytical frameworks that are used within the disciplinary field. All of the papers of the conference showed the powerful impacts that can be made by the subject area and how it can engage in cross-disciplinary research of crucial importance. The engagement of teams of researchers in high-profile funding initiatives such as OWRI leads to innovation in teaching practice and to changes in public perception.

The conference, with short interventions focussing on issues of strategic significance to everyone within the sector, provides an excellent model for future events. The recording of the event is available here:

Charles Burdett, Director of the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Translating César Vallejo’s poem ‘Trilce III’

Cynthia Stephens translates this poem from the collection ‘Trilce’ (1922). This is a literary translation, which attempts to create a new poem while remaining faithful to the original. Some of the difficulties which arise in such a translation are discussed, as it is a semantically complex poem in which multiple meanings echo through the voice of the scared child to that of the terrified adult.

Poet – César Vallejo

Original Poem:

Trilce III

Las personas mayores

¿a qué hora volverán?

Da las seis el ciego Santiago,

y ya está muy oscuro.

Madre dijo que no demoraría.

Aguedita, Nativa, Miguel,

cuidado con ir por ahí, por donde

acaban de pasar gangueando sus memorias

dobladoras penas,

hacia el silencioso corral, y por donde

las gallinas que se están acostando todavía,

se han espantado tanto.

Mejor estemos aquí no más.

Madre dijo que no demoraría.

Ya no tengamos pena. Vamos viendo

los barcos ¡el mío es más bonito de todos!

con los cuales jugamos todo el santo día,

sin pelearnos, como debe de ser:

han quedado en el pozo de agua, listos,

fletados de dulces para mañana.

Aguardemos así, obedientes y sin más

remedio, la vuelta, el desagravio

de los mayores siempre delanteros

dejándonos en casa a los pequeños,

como si también nosotros

no pudiésemos partir.

¿Aguedita, Nativa, Miguel?

Llamo, busco al tanteo en la oscuridad.

No me vayan a haber dejado solo,

y el único recluso sea yo.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Poet – César Vallejo

Translation:

Trilce III

Where have the grown-ups gone?

When will they get home?

Darkness has fallen in our village now,

it’s six o’clock and the light has gone.

Blind Santiago is ringing the bells.

Mother said she wouldn’t be long.

Aguedita, Nativa, Miguel,

be careful going out there, where

the souls of the dead have just passed,

sounding a death knell.

Double sorrows, ghosts,

are dragging their twanging memories

through our silent yard,

squawking, suffering, haunting.

So the sleeping hens

have been spooked and frightened away.

Better for us just to stay here quietly.

Mother said she wouldn’t be long.

We mustn’t be sad now.

Let’s go and look at our toy boats.

Mine is the prettiest of them all!

We’ll play with them the whole blessed day,

without fighting, as it should be:

they’re still in the pool, ready,

loaded up with sweet things for tomorrow,

ready for departure.

Let’s wait like this then, obediently,

not that we have any choice.

Let’s wait for them patiently,

for an apology from the two-faced grown-ups,

who are always ahead,

leaving us, the little ones, at home,

as if we couldn’t

as if we couldn’t also go away.

Aguedita, Nativa, Miguel?

I’m afraid of this punishment.

I call out, groping in the darkness,

searching through trial and error.

Surely they haven’t left me all alone,

in jail, doubled-up in pain.

Why am I the only prisoner?

The only condemned one!

Translation by Cynthia Lucy Stephens

Copyright © 2022

Commentary:

This haunting poem by the great Peruvian poet César Vallejo is about fear and loss. It expresses grief at the deaths of his brother Miguel followed by his mother, and the dreadful solitude following the break-up of his family and the end of his childhood. I see also the persecution and solitude later felt by Vallejo in his prison cell in Peru in 1920, held under never-proven charges, before he escaped on a boat to France and a life of exile.

I have tried to capture some of the multiple meanings echoing throughout this evocative poem. I divided the long sentence, in order to express double-edged meanings in the phrase “gangueando sus memorias / dobladoras penas”. “Gangueando” means “twanging” and “speaking through the nose”. I chose “squawking” because of the hens, but also because its discordant tones convey the difficulty of expressing painful memories. I focused on the active presence of the dead. “Penas” can mean “sorrows” or “souls of the dead” or “punishments”. “Dobladoras” could be “double”, “duplicitous”, or “doubled-over”, but I also wanted the sense of “doblar campanas”, to “toll”, or “doblar a muerto”, to “sound a death knell”, so as to connect with the blind bell-ringer Santiago from his childhood village.

The souls of the dead follow the child and the man, as the child waits in the village for his parents to come home, and in the last stanza the man reaches out for his lost siblings in the jail. He is afraid, like the hens from his childhood yard; he fears he may be left alone forever in a prison cell. This is a poem about departures and people not coming back home. Perhaps also a fear of his own future exile can be glimpsed within the ambiguous connotations of this complex poem.

Cynthia Stephens is a member of the Chartered Institute of Linguists (MCIL), the Association of Hispanists of Great Britain and Ireland (AHGBI), and the Modern Humanities Research Association (MHRA). She studied English and Spanish at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, graduating in 1978, and that is where she discovered the poetry of the great Peruvian poet César Vallejo. She has recently translated a chapter of the book César Vallejo’s Season in Hell, from Vallejo en los infiernos by Eduardo González Viaña, co-ordinated by Stephen M. Hart.

Translating César Vallejo’s poem ‘Enereida’

Cynthia Stephens translates this poem from the collection ‘Los heraldos negros’ (The Black Heralds) (1918). This is a literary translation, which attempts to create a new poem while remaining faithful to the original. Some of the difficulties which arise in such a translation are discussed, including how to render the made-up word title, which is probably a reference to January and a departure.

Poet – César Vallejo

Original Poem:

Enereida

Mi padre, apenas

en la mañana pajarina, pone

sus setentiocho años, sus setentiocho

ramos de invierno a solear.

El cementerio de Santiago, untado

en alegre año nuevo, está a la vista.

Cuántas veces sus pasos cortaron hacia él,

y tornaron de algún entierro humilde.

¡Hoy hace mucho tiempo que mi padre no sale!

Una broma de niños se desbanda.

Otras veces le hablaba a mi madre

de impresiones urbanas, de política;

y hoy, apoyado en su bastón ilustre

que sonara mejor en los años de la Gobernación,

mi padre está desconocido, frágil,

mi padre es una víspera.

Lleva, trae, abstraído, reliquias, cosas,

recuerdos, sugerencias.

La mañana apacible le acompaña

con sus alas blancas de hermana de la caridad.

Día eterno es éste, día ingenuo, infante,

coral, oracional;

se corona el tiempo de palomas,

y el futuro se puebla

de caravanas de inmortales rosas.

Padre, aún sigue todo despertando;

es enero que canta, es tu amor

que resonando va en la Eternidad.

Aún reirás de tus pequeñuelos,

y habrá bulla triunfal en los Vacíos.

Aún será año nuevo. Habrá empanadas;

y yo tendré hambre, cuando toque a misa

en el beato campanario

el buen ciego mélico con quien

departieron mis sílabas escolares y frescas,

mi inocencia rotunda.

Y cuando la mañana llena de gracia,

desde sus senos de tiempo,

que son dos renuncias, dos avances de amor

que se tienden y ruegan infinito, eterna vida,

cante, y eche a volar Verbos plurales,

jirones de tu ser,

a la borda de sus alas blancas

de hermana de la caridad, ¡oh, padre mío!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Poet – César Vallejo

Translation:

Fly Free January

In the fledgling morning

my ancient father,

with his seventy-eight long years,

can scarcely drag his winter branches,

all seventy-eight of them,

into the warmth of the sun.

He sees the local cemetery of Santiago de Chuco,

anointed by a merry New Year.

Many a time he took the village shortcut here,

walking, to attend some humble burial,

then making his way back home again, on foot.

Now it’s a long time since my father even left the house!

His children have fluttered and scattered away,

as if having some kind of a joke.

In the past he would discuss city matters,

public life and politics, with my mother;

but today he leans on his distinguished walking stick,

which sounded better in past times,

when the Government was in power.

My father is a different person now,

fragile and unfamiliar.

He’s on the eve of a big event,

awaiting a new beginning, a rebirth.

Withdrawn, he picks things up

and then puts them back again,

relics, memories, suggestions of things past.

The pleasant morning accompanies him,

with its Sisters of Charity white wings.

This is an eternal day, naïve and innocent;

child-like and choral, it resembles a prayer;

time is crowned with doves,

and the future is planted with caravans of roses

moving towards immortality.

Father, everything is still awakening;

January is singing, with mirth,

for the rebirth of the year;

your love echoes and rings on its journey to Eternity.

You will be laughing soon at your own little baby ones,

and their triumphal racket will fill the silence of the Void.

It will still be New Year’s day, like long ago.

Festive pies will be served, and I will be very hungry

when the bell is rung for mass in the blessed belfry,

by Santiago, the good blind man.

His conversation was so lyrical,

when I used to chat with him,

and share my fresh schoolboy syllables,

my resounding innocence.

When the new morning comes, full of grace,

its breasts of time two renunciations,

two points of love advancing;

Sister of Charity nuns, with white veils flowing,

and white sheets laid out, will pray,

reciting the Word, for infinite, eternal life.

The morning will sing out loud, and plural Verbs,

the tatters of your fragile self, will be set free;

white wings sailing over the edge, into Eternity.

Oh, my fledgling father, in January

you too, like a white dove, will fly away.

Translation by Cynthia Lucy Stephens

Copyright © 2022

Commentary:

This haunting poem by the great Peruvian poet César Vallejo is a filial tribute expressing love. It is about Vallejo’s old fragile father, who is struggling with his life after the death of his wife and the break-up of his family. The poem takes place on New Year’s day, and the father is portrayed as being like a young bird about to fly away sometime in January.

The title “Enereida” is a made-up word, possibly from “Enero” (January) and “ida” (departure). There may also be a reference to Virgil’s Aeneid, in which the themes of rebirth and filial piety are both important. I found translating the title the hardest part; I started with an ugly made-up word, but I ended up with a title that I like the sound of and that I think is more optimistic.

I tried to capture some of the multiple meanings within this valedictory poem. The last stanza was particularly challenging due to many interacting symbols, and entangled syntax. I split this stanza into two; in the second section I have been more “creative”, so as to encompass the wider connotations. For instance, I focus on the Sister of Charity nuns, and their white wings become white veils; also white sheets, which are laid out; this is justified by the text, as “tender” can mean to lay out a dead body. I also added the reference to a white dove in the last line, but I think this is justified as doves are mentioned in the poem, and their white wings reflect those of the nuns.

The poem is imbued with religious imagery. I used the full name of Santiago de Chucho, the village where Vallejo grew up, as for British readers Santiago tends to mean Santiago de Compostela; and I gave the blind man his real name, Santiago. Language parts participate in the poem, in the form of Syllables and plural Verbs. I have the praying nuns reciting the Word. At the end of the poem I make explicit the idea that the fragile father, like a fledgling bird, will soon fly away to a new life in Eternity.

Cynthia Stephens is a member of the Chartered Institute of Linguists (MCIL), the Association of Hispanists of Great Britain and Ireland (AHGBI), and the Modern Humanities Research Association (MHRA). She studied English and Spanish at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, graduating in 1978, and that is where she discovered the poetry of the great Peruvian poet César Vallejo. She has recently translated a chapter of the book César Vallejo’s Season in Hell, from Vallejo en los infiernos by Eduardo González Viaña, co-ordinated by Stephen M. Hart

(Mis)translating Deceit: Disinformation’s Hidden Translingual Journey

Stephen Hutchings and Vera Tolz discuss how Modern Languages expertise can illuminate hitherto unacknowledged, but critically important, aspects of a major societal challenge: disinformation

COVID-19 and America’s Russia Gate scandal highlighted the threat posed by disinformation, generating multiple counter-disinformation initiatives – fact-checkers, monitoring organizations, legislative restraints, and online literacy initiatives. These reflect legitimate concerns implicating authoritarian states, but they also point to what a respected US journalist recently termed a ‘Big Disinfo’ knowledge industry.

An enduring ‘Big Disinfo’ fallacy posits ‘disinformation’ as a mid-20th-century English translation of the Soviet term ‘dezinformatsiya’, coined deceptively to resemble a French word, and a practice of non-Soviet origins. Disinformation is thus fundamentally inflected by (mis)translation, and history. The conventional wisdom is flawed (the term first occurs in early 20th-century English parliamentary disputes), indicating further that, rather than designating demonstrable falsehood, to identify something as ‘disinformation’ is a communicative, historically contextual act either inculpating other states or ‘othering’ internal critics. This explains why, when it is discovered locally, we have, since the Cold War, tended to seek evidence of foreign co-production; why the presence of non-Latin script on digital platforms can be over-interpreted as evidence of hostile state involvement; and why we often differentiate domestic ‘misinformation’ (unintentional falsehood) from foreign ‘disinformation’ (deliberate falsification), despite the impossibility of corroborating distinctions in an online world replete with camouflage.

Since English still dominates the digital realm harbouring most contemporary disinformation, it is the main target for disinformation producers. Conversely, its trackers prioritise anglophone examples of it. But what do we miss by disregarding disinformation’s hidden journey across multiple linguistic borders and communicative and conceptual contexts, its calibration for and interpretation by multilingual audiences, and its associated fluidity as a term of accusatory practice?

The main American and British English language corpora suggest that, excluding the world wars, from the term’s first appearance in the 1880s two historical points witnessed dramatic increases in western attributions of disinformation to foreign adversaries: the early 1980s and the 2016-2019 period. The relevant adversaries were respectively the USSR and Russia. Similarly, in both periods the initial obsession with foreign disinformation eventually gives way to concerns with internal culprits. Both periods, too, start with high-profile polarizing votes (the elections of Thatcher and Reagan; that of Trump and the Brexit referendum).

While in the early 1980s, the English language corpora’s examples primarily invoke KGB/Soviet disinformation, the mid-1980s saw annual increases in the term’s usage (continuing into the 21st century), but now as insults traded among internal opponents – Labour and Tory MPs, Democrats and Republicans.

In the second period, 2016 witnessed a sharp spike in accusations against Russia. This is unsurprising, given the Kremlin’s well-documented interference in the US elections. However, by 2019, according to the Corpus of Contemporary American English, only 15% of examples name Russia, with the majority of disinformation culprits internal to the US.

Accusations against the USSR dropped after 1985 despite the most effective Soviet disinformation campaign ever – claiming that HIV/AIDS originated in a US laboratory – peaking in 1985-1988. The campaign’s failure to penetrate anglophone public debates reflected improvements in Soviet-Western relations under Gorbachev. Internally, disinformation allegations now, however, benefited from polarization generated by Reagan’s and Thatcher’s policies. Similarly, by 2019 disinformation discourse again targeted internal divisions within anglophone societies. Significantly, peaks and troughs in instances of ‘dezinformatsiya’ in the Russian national corpus follow patterns similarly dictated by international relations, alongside episodes involving the inverted mirroring of Western accusations. .

What of disinformation’s contemporary translingual trajectories? One narrative branded as disinformation by its leading European tracker is the ‘Russophobia’ accusation levelled by the Kremlin at western powers. Deployed recently to rebut allegations of demonstrable Kremlin involvement in the Salisbury poisonings this narrative sometimes involves deliberate deceit but more often reflects Russia’s historical defensiveness vis-à-vis the West and residual imperial rivalry (‘Russophobia’ featured in 19th-century English and Russian). That the same term is used polemically by opposing sides both to exemplify and to disprove current disinformation demonstrates why it works poorly as a forensic tool. Interestingly, despite the equivalent term’s minimal presence in German, ‘Russophobie’ is a search term on the RT Germany website, seen as a prime disinformation culprit. Moreover, the EU disinformation tracker lists as a source propagating the Russophobia narrative a Sputnik France article from which the term is entirely absent. The unacknowledged migration of concepts across languages and history, between allegation and rebuttal, and from rhetorical device to forensic tool, proves deeply problematic.

Another pernicious narrative of the COVID period revived the western-produced biological weapon myth. Aired throughout Russian-language media (but traceable to US ‘deep state’ conspiracists with whom Russophone extremists co-produce narratives), the theory was targeted by the EU’s counter-disinformation unit which tracked one example to a nationalist website hostile to the Kremlin. Yet the source associates the notion of COVID as ‘a British weapon’ with Western conspiracy sites , and the author concedes that Coronavirus’s probable origin is non-human. The article is highly tendentious but listing it as ‘pro-Kremlin disinformation’ is triply inaccurate.

Context – historical and linguistic – matters. For most anglophones the ‘bio-weapon’ story is conspiratorial nonsense, but for Arabic speakers sensitized to postcolonial paradigms, it re-invokes colonial aggression – hence the theory’s Arabic-language prevalence. Russian broadcaster, RT Arabic, is cited by the same disinformation tracker as concocting a claim that COVID-19 is a US biological weapon. Closer scrutiny reveals that RT merely reports the claim by an Iranian official (admittedly without challenging it). Attention to a narrative’s surrounding linguistic context is essential to confirming its ‘disinformation’ status.

Disinformation trackers combine misattribution of narratives with mis-readings of their purpose. Another Russophone outlet was accused of claiming that COVID-19 was designed to kill elderly Italians. This source, however, targeted Latvians exposed to mainstream European media and was clearly ridiculing conspiracy theories. Indeed, Russia’s French-language output absorbed much of the mainstream anti-conspiracy rhetoric, re-deploying it for polemical ends, as in RT’s denunciation of France’s leading bookseller for promoting COVID disinformation, including the bio-weapon story.

The contradictions reflect uncritical usage of the term ‘disinformation’ to demarcate the Self (as upholder of truth) and the Other (as promoter of deceit) – hence the tendency to attribute the concept to the Other’s language; the confusion of polemical and partisan bias with disinformation; and the historical oscillations between projections of deceit onto internal and external adversaries respectively. These conflations are exacerbated by Big Disinfo’s perceived need to match volumes of disinformation identified to levels of funding received.

Inattention to disinformation’s translingual contexts, trajectories and narratives bolsters the dynamic sustaining it, to the advantage of authoritarian state actors like RT, which has launched its own multilingual ‘counter-disinformation’ initiative. Like ‘Big Pharma’, Big Disinfo shows scant respect for borders (of politics, language, or state). This confirms the value of retracing the steps of disinformation’s hidden journey.

Stephen Hutchings, Professor of Russian Studies, University of Manchester

Vera Tolz, Professor of Russian Studies, University of Manchester

Transnationalising the Word: The Present and Future of Education in Modern Languages

Transnational and decolonisation approaches are shaping the present and future of Modern Languages, which makes the dialogue between research and teaching more important than ever before. Marcela Cazzoli and Liz Wren-Owens discuss whether we are ready for the challenge.

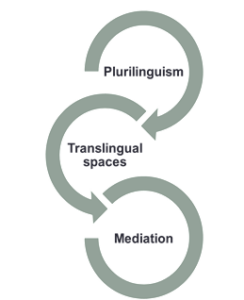

The keystone Transnational Modern Languages project was fundamental in encouraging an overdue transformation in the discipline, identifying a set of issues that research and teaching in Modern Languages would need to challenge to remain sustainable and relevant and to ensure that the true value of the discipline was clearly legible to those outside the subject area. The TML project enabled us to reframe the disciplinary framework of Modern Languages, arguing that it should be seen as an expert mode of enquiry whose founding research question is how languages and cultures operate and interact across diverse axes of connection. Central to the debate was the interrelationship between languages and cultures and the necessity to leave monolingual traditions behind, to uphold the real picture of how languages engage with the contemporary global world.

Those of us teaching in schools of Modern Languages have known about this first hand: we are incredibly lucky to be surrounded by different languages and immersed in a wealth of linguistic and cultural diversity that we sometimes take for granted. Yet, our curricula may still hold us back, reflecting a vision of Modern Languages teaching and research that sees culture through the lens of language, and language through the lens of skills. The (Re)Creating Modern Languages project (Beaney et al, 2020), for instance, has provided guidance on how we might think about revising our curricula, identifying areas to consider in terms of structures of programmes, engagement with the wider socio-cultural perspective, the scope of our cultural focus, and identifying (and overcoming) barriers to change.

If we are serious about engaging our students with a discipline that reflects the reality of the transnational, translinguistic, and transcultural world of today, a global understanding of languages that works in synch with decolonising approaches is crucial. Are we committed to tackling the linguistic indifference of postcolonial studies? How complicit are we in allowing Anglo words and Eurocentric frameworks to dominate the narrative of practices and identities? Decolonisation projects developed in universities across the UK have provided further support to transnational approaches, as they both aim to decentre and challenge methodological nationalism and propose an inclusive view of multilingualism and multiculturalism.

How do we use transnational and decolonising approaches to design our teaching? The Transnationalising the Word symposium began a conversation that has hopefully raised awareness and provided some reassurance that it can be done. The well-thought out presentations, linking research with practice, provided examples and insights for the way forward. We have been able to ask ourselves very useful and, at times, uncomfortable questions that can help us think through how we might revise our programmes or curricula. In his opening paper, Decolonising the Chinese Curriculum: Indigenous Epistemology and Translanguaging, Danping Wang discussed how different epistemological approaches can reframe the learner-teacher relationship and asked us to unlearn our current assumptions and  open up our imaginations. This notion of unlearning and opening is a powerful notion that can shape our approach not only to questions of transnationalising and decolonising our curricula, but in thinking through our teaching more broadly. Other presentations throughout the day further probed how connections and collaborations might be fostered between languages and culture, and the ways in which languages other than English are valued as effective means of resistance to (mental) colonisation. Excellent projects were showcased which suggested practical ways of shaping our teaching and, importantly, our assessment, to enable students to engage with the ways in which culture shapes languages and both are informed by power dynamics often linked to colonial histories. Alexandra Lourenço Dias’ Decolonised Dictionary of the Portuguese Language Project, for example, explored how students can reflect on the interrelationships between language, culture, and power through the development of an exciting new resource that focuses on terms are that articulated differently in parts of the Portuguese-speaking world based on the local culture and their history. Angela Viora’s presentation, Cities, Landscapes, and Ecosystems: Exploring Contemporary Italy Through Local Responses to Global Challenges. Creativity, Interdisciplinarity, and Decolonisation and Salvatore Campisi’s Reflecting on and Challenging Narratives of Italy and Italian with Students opened up questions of how transnationalising and decolonising the curriculum might enable us to re-think the cultural materials that we study. They offered fascinating examples of how street art, itinerant performers, oral histories sourced by students from the local community, rap, and public statues and memorials can be leveraged to encourage students to reflect on transnational and decolonising histories. Viviane Carvalho da Annunciação’s work on Decolonising Portuguese Language Classes explored the extent to which the diverse backgrounds that students bring to the classroom are reflected (or not) in pedagogical practice and examined how our practice be adjusted to enable and empower students from minority backgrounds, from the study of languages in schools through to undergraduate programmes.

open up our imaginations. This notion of unlearning and opening is a powerful notion that can shape our approach not only to questions of transnationalising and decolonising our curricula, but in thinking through our teaching more broadly. Other presentations throughout the day further probed how connections and collaborations might be fostered between languages and culture, and the ways in which languages other than English are valued as effective means of resistance to (mental) colonisation. Excellent projects were showcased which suggested practical ways of shaping our teaching and, importantly, our assessment, to enable students to engage with the ways in which culture shapes languages and both are informed by power dynamics often linked to colonial histories. Alexandra Lourenço Dias’ Decolonised Dictionary of the Portuguese Language Project, for example, explored how students can reflect on the interrelationships between language, culture, and power through the development of an exciting new resource that focuses on terms are that articulated differently in parts of the Portuguese-speaking world based on the local culture and their history. Angela Viora’s presentation, Cities, Landscapes, and Ecosystems: Exploring Contemporary Italy Through Local Responses to Global Challenges. Creativity, Interdisciplinarity, and Decolonisation and Salvatore Campisi’s Reflecting on and Challenging Narratives of Italy and Italian with Students opened up questions of how transnationalising and decolonising the curriculum might enable us to re-think the cultural materials that we study. They offered fascinating examples of how street art, itinerant performers, oral histories sourced by students from the local community, rap, and public statues and memorials can be leveraged to encourage students to reflect on transnational and decolonising histories. Viviane Carvalho da Annunciação’s work on Decolonising Portuguese Language Classes explored the extent to which the diverse backgrounds that students bring to the classroom are reflected (or not) in pedagogical practice and examined how our practice be adjusted to enable and empower students from minority backgrounds, from the study of languages in schools through to undergraduate programmes.

A few presentations offered useful insights into how the publications emerging from the Transnational Modern Languages project, in Liverpool University Press’ Transnational Series, might provide teachin g tools as we re-think our approach to teaching language, culture, and history. Derek Duncan & Jenny Burns’ presentation on Thematic Cartographies: Transnational Modern Languages and Cecilia Piantanida’s Hybridity and Transnationalism in the Modern Language Class suggested ways of challenging student preconceptions of cultures and nations by adopting a transnational and decolonising approach to teaching, thinking through how idealised and essentialised notions of specific cultures can be leveraged by the far-right.

g tools as we re-think our approach to teaching language, culture, and history. Derek Duncan & Jenny Burns’ presentation on Thematic Cartographies: Transnational Modern Languages and Cecilia Piantanida’s Hybridity and Transnationalism in the Modern Language Class suggested ways of challenging student preconceptions of cultures and nations by adopting a transnational and decolonising approach to teaching, thinking through how idealised and essentialised notions of specific cultures can be leveraged by the far-right.

The symposium was a valuable source of inspiration, exchange and connection. The conversations begun on the day will no doubt develop and evolve in fruitful ways. We would like to thank all contributors, including our excellent presenters and colleagues who participated in the rich discussions. We would also like to thank the IMLR and UCML for their support in bringing the symposium into being. We are keen to use this as a starting point for further work on the way in which transnationalising and decolonising approaches can further enhance our teaching, and look forward to talking, listening, and learning more.

Dr Marcela Andrea Cazzoli, (Durham) Associate Professor (Teaching) / Director of UG Education

Dr Elizabeth Wren-Owens (Cardiff), Director of Postgraduate Research and Deputy Head of School