Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

An Olympic Opening Ceremony with a Difference: a Spectacle of Revolutionary Struggle in the Robert Lucas Papers

As the insistence that politics should be kept out of the Olympics comes under increasingly scrutiny, Miller Archivist Clare George looks in the IMLR’s archives of German-speaking exiles, at records of an Olympics Games ninety years ago which was an expressly political act.

In July 1931 the second International Workers’ Olympiad was held in Vienna by the Sozialistische Arbeiter-Sport-Internationale (SASI) as a celebration of international solidarity rather than competition. With over 100,000 athletes from 26 countries, the event was far bigger in terms of participants than the International Olympics Committee Olympiad in Los Angeles the following year.

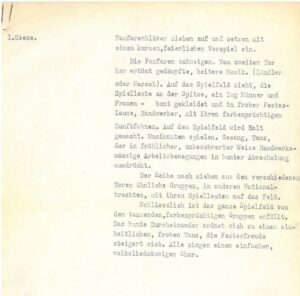

As with the IOC Olympics, the artistic opening ceremony to the Games in Vienna projected a cultural narrative onto the event, but unlike most such ceremonies since 1936 at least, its theme was not the host nation’s achievements and triumphs but international revolutionary struggle. Das Spiel der Viertausend (the Pageant of the Four Thousand) was created by Austrian socialist journalist and writer and later refugee, Robert Ehrenzweig, to unite participants and spectators in the story of the liberation of the proletariat against capitalist oppression.

Four thousand volunteers from the Austrian Social Democratic Party performed in the spectacle as craftsmen, farmers, soldiers, cobblers, weavers, spinners, blacksmiths, tailors, telephonists, typists and other workers. An instruction booklet published by the Party set out Ehrenzweig’s stage directions for the players, furniture and props, which included 12 tables, 24 typewriters, 4 megaphones, 40 stools and 40 distaffs. It also explained how costumes would be allocated. Outfits for craftsmen, farmers and weavers would be provided by the organisers, for example, but the 80 young socialist actors playing fascist paramilitaries would need to bring their own black shirts.

In the centrepiece of the arena a mass of scaffolding was erected decked with billboards promoting the instruments of the market system: ‘stock exchange’, ‘shares’ and ‘balances’, and topped with the cold giant face of capitalism. A Berlin newspaper reported the ‘overpowering first impression presented to the audience on entering the stadium: the vast arena, in the middle of which loomed the Tower of Capitalism, the colourful ring of the masses around the outside’.

RLU/1/2/5 Preparing the set: constructing the Tower of Capitalism (Photograph by Leo Ernst / Albert Hilscher)

Lucas had already established himself as a writer of political cabaret satirising the right wing of his Party, but his Olympics opening production was theatre on an entirely different scale. Das Spiel der Viertausend was one of the largest mass spectacles that had ever been staged. Organisers had planned two performances, during the opening and closing ceremonies – but the demand for tickets was so great that a further two performances had to be arranged hurriedly at the last minute. In all, more than 260,000 viewers saw the production over the course of the four performances. Around 20,000 of them had forged tickets, according to the Vienna police!

Three years later, with the establishment of the Austrofascist regime in 1934, Ehrenzweig left Austria for the UK, where he changed his name to Lucas and eventually found work with the BBC’s German Service. The records in this archive are a reminder of an international mass movement that was well-organised, strong and deeply rooted in working-class culture. The International Workers’ Olympics aimed to push back against the wave of nationalism that was then sweeping through Europe and beyond and provided an opportunity for athletes from different counties to compete against each other within the ideological context of international socialism and strengthening solidarity.

The papers of Robert Ehrenzweig /Lucas were kindly donated in 2015 by his sons David and John Lucas. A catalogue is available online here: https://archives.libraries.london.ac.uk/Details/archive/110050239 and the material is open for consultation in Senate House Library. A film of the 1931 Vienna International Workers’ Games can be seen here: http://mediawien-film.at/film/319/.

Dr Clare George, Miller Archivist (Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies)

Freud’s Archaeology. A conversation between analysis and excavation

IMLR Sylvia Naish Fellow, Frederika Tevebring, discusses Freud’s parallels between archaeology and psychoanalysis. Special Issue of American Imago, vol. 78, no.2 (Summer 2021)

In the summer of 2019 the Warburg Institute, in collaboration with the University of Chicago and the Freud Museum, hosted the conference “Freud’s Archaeology,” exploring Freud’s self-proclaimed “obsession” with antiquity and the importance of archaeology in his conceptualisation of psychoanalysis. From this event, a special issue was conceived that will appear in American Imago.

Freud’s library, as well as his own texts, are replete with references to excavation, buried cities, and to the works of archaeologists and philologists. Following his father’s death in 1896 he became an avid collector and began to crowd his office and consulting room with archaeological objects. His favourite statuettes – fondly referred to as his “old grubby gods” – were arranged in neat rows on his desk so that they could gaze over him when he was writing. His collection never spilled over from his working space into the family’s living room and, similarly, his regular trips to Italy were undertaken with colleagues (or his brother) rather than in the company of wife and children. Freud’s relation to the ancient Mediterranean was deeply personal, but linked to his identity as the founder of a new science. The work of archaeology and psychoanalysis, he insisted, was in fact “identical.”

Figure 1 so-called Baubo statuette. Terracotta votive from Priene, modern-day Turkey. Excavated in 1898. Berlin Antikensammlung

For Freud, psychoanalysis and archaeology both share the task of retrieving memories out of sedimented depths and incorporating these memories into the present. This parallel is often glossed as a “metaphor,” perhaps most famously in Donald Kuspit’s 1989 essay on archaeology as the “mighty metaphor” of Freud’s work. “Metaphor,” however, simplifies the unique ways that Freud deploys likenesses and parallels in his writing. A metaphor is commonly understood as an illustrative comparison between something well-known and something lesser known. Freud, however, often insists on identity rather than comparison. Moreover, when he presents us with parallels such as an “exact correspondence” between the relatively recently excavated “Baubo” figurines (Figure 1) and his patient’s Oedipally-informed visual obsession (“A Mythological Parallel to a Visual Obsession,” 1916), we can no longer be certain which of the pair is supposed to be the well-known, and which the lesser-known example. Is archaeology elucidating psychoanalysis or the other way around?

In Freud’s Archaeology, the authors’ backgrounds in archaeology, classics, art history, and German literature shift the focus away from treating archaeology as a self-explanatory practice; instead, these diverse perspectives help to situate Freud’s interest within the history of the discipline, his intellectual milieu, and geopolitical circumstances. Like any of his bourgeois contemporaries, Freud received an education with a strong foundation in classical literature and would have been introduced early to the idea of Greece and Rome as the “childhood” of modern European culture. Freud’s archaeology is hence, without a doubt, a Eurocentric one: it excavates the biography of the – implicitly male – European subject who has claimed the classical past as his heritage. Archaeology had developed hand-in-hand with European colonial interests and took for granted that Europeans were best positioned to explore and safe keep the heritage of the world. Neither is Freud particularly interested in the discoveries of prehistoric central Europe. The archaeology he refers to is undertaken in exotic locations by larger-than-life personalities – such as Howard Carter or Heinrich Schliemann – to the admiration and media attention of the nation back home.

However, while Freud considered human culture to develop in an analogous way to individual maturation, the psychosexual framework of his developmental narrative by necessity gravitated towards the dark and uncomfortable. In texts such as Totem and Taboo, he insists upon a common primitive heritage from which all socialized humanity emerged. Contemporary excavations, such as Sir Arthur Evans’ descriptions of goddess-worshipping Minoans on Bronze-Age Crete, inspired Freud to ask about the lingering residues from a shared past that he – and most of his contemporaries – described as feminine and irrational. While Freud would agree with the common narrative of history as progressive rationalisation, he differed in his conviction that earlier stages were never completely done with. We, individually and collectively, carry our unruly, uncivilised past with us.

Dr Frederika Tevebring, 2020-21 Sylvia Naish Fellow, Institute of Modern Languages Research

Refugee Week 2021: On the Trail of Refugees in 1930s Bloomsbury (part 2)

To mark Refugee Week later this month (14-20 June), the IMLR is running a guided walk around Bloomsbury following the trail of the 1930s refugees from Nazi Europe. The walk brings to life work by the Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies and uses voices and images from the IMLR’s exile archives to illustrate the stories uncovered by this research. This is the second of two blog posts by Miller Archivist Clare George on the Bloomsbury sites that played a role in this refugee community’s histories.

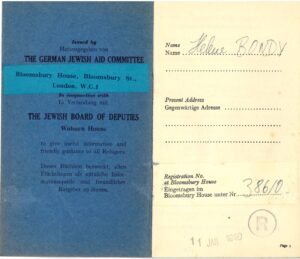

Few of the refugees from Nazi Germany had the means to support themselves in the UK and many relied on the myriad of voluntary organisations that sprang up to provide help with everything from welfare to visa applications and employment. As the offices of these bodies were concentrated in the district, Bloomsbury saw a daily influx of visitors arriving to register with them and seek assistance. Amongst the earliest was the Germany Emergency Committee, established by the Society of Friends in Euston Road in 1933, and the Jewish Refugees Committee, set up by Jewish community leaders at Woburn House in Tavistock Square in the same year. The Academic Assistance Council moved into Gordon Square in 1936 and was followed by the Church of England Committee for non-Aryan Christians in 1937. To the south of the district, in New Oxford Street, was Austrian Self Aid, one of the first groups set up by refugees themselves to help those still trying to leave Austria, and the Czech Refugee Trust Fund, the only organisation to receive government funding, had its offices in Mecklenburg Square. During the Second World War, an overarching committee coordinating these and other support organisations was formed and moved into 21 Bloomsbury Street, formerly the Palace Hotel. Bloomsbury House, as it was known to the refugees, provided office space for as many as 30 voluntary bodies and became the central registration point for all refugees from Nazi Germany.

‘While you are in England. Helpful information and guidance for every refugee’, issued to Helene Bondy by the German Jewish Aid Committee, Bloomsbury House, and the Jewish Board of Deputies, Woburn House, 1940 (Paul and Charlotte Bondy papers)

Recommendations of the Boards of Studies regarding displaced University Lecturers, Academic Assistance Council, University correspondence for the session 1933-1934 (UoL/CF/1/34/721)

The increasing presence of the University of London in Bloomsbury was another reason refugees were drawn to the district. The building of Senate House and the movement of the University’s administrative centre from Kensington to Bloomsbury in the 1930s had been driven by William Beveridge, Vice Chancellor of the University from 1926 to 1928. Beveridge was also behind the establishment of the Academic Assistance Council, a scheme supporting German Jewish academics dismissed from their posts following the passing of anti-Semitic legislation in Germany in April 1933. The University’s Boards of Studies liaised with the Council over displaced lecturers and by July 1935 had provided 55 temporary teaching or research posts to refugee academics, more than any other British university.

Educational institutions of various kinds were of course already long established in the neighbourhood, and the attendant student accommodation and clubs which spread across the district also played a role in the refugees’ history. Student Movement House, occupying the original Georgian building at 32 Russell Square until it was demolished in March 1939, was a social club run by the Student Christian Movement for international students. It included both Nazi and Jewish German students in the pre-war years, and the warden later recalled the poverty-stricken conditions in which refugee students lived in the backstreet slums of the district. Canterbury Hall in Cartwright Gardens was another a student facility with a historical connection to the refugees. A hall of residence until the start of the war, when the students were evacuated it was given over for the accommodation of members of the Czech Refugee Trust Fund in April 1940 and it became known to MI5 as a hotbed of Communist agitation.

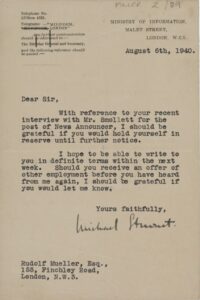

Interview invitation from the Ministry of Information at Senate House to Austrian Jewish actor Martin Miller, 1940 (Miller/2/89)

In 1939 the newly built Senate House was emptied of most of the University’s administrative departments and filled instead with civil servants, journalists and others working for the Ministry of Information. Responsible for wartime publicity and propaganda, the Ministry of Information employed and commissioned artists, writers, journalists, researchers, and film directors. As a high proportion of refugees were from the creative industries and had journalistic and artistic skills and experience, and were also highly motivated to join the war against Hitler, many of them made an important contribution to the Ministry’s mission.

To find out more about this and other sites of historical importance to the refugees, please join us for a free guided tour led by Clare George (Miller Archivist/Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies at the IMLR). Advanced booking is required. Please follow one of the following links to book:

17 June 2021, 11.00am – 12.30pm

19 June 2021, 11.00am – 12.30pm

Those who cannot make the guided walks, could instead listen to our audio walk, created for the Being Human Festival in November 2020.

Dr Clare George, Miller Archivist/Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies at the IMLR

Refugee Week 2021: On the Trail of Refugees in 1930s Bloomsbury (part 1)

The Refugee Week theme this year is ‘We Cannot Walk Alone’, and the IMLR is marking it with a guided walk around Bloomsbury following the trail of the 1930s refugees from Nazi Europe. The walk brings to life work by the Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies and uses voices and images from the IMLR’s exile archives to illustrate the stories uncovered by this research. This is the first of two blog posts by Miller Archivist Clare George on the Bloomsbury buildings and institutions that played a role in the history of this community.

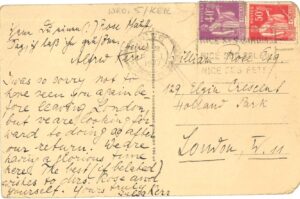

Postcard from Julia and Alfred Kerr to German Studies scholar and refugee supporter William Rose, 1937 (WRO/5/KER)

The ‘On the Trail of Refugees’ tour traces the many sites which drew the 1930s refugees from Nazi Europe to Bloomsbury. The district’s cheap accommodation, relative to its central location, was one of the main attractions for the new arrivals. The experience of refugee life in one of the district’s low-budget boarding houses was captured by writer Judith Kerr in her semi-autobiographical novel Bombs on Aunt Daisy. The tour takes in the site of the Kerr family’s home from 1935 until the Blitz, the former National Hotel in Bedford Way, immortalised in the novel as the Hotel Continental. Extracts from oral history audio recordings will allow participants to hear other refugees recalling their experiences of staying in Bloomsbury’s boarding houses in the early days of the Second World War.

For the many artists and writers amongst the refugees, Bloomsbury’s Bohemian reputation added to its appeal. The Austrian author Hans Flesch-Brunningen, who was taken by a friend to a boarding house in the district immediately after his arrival in the UK, was one of those who fell under Bloomsbury’s spell. His enchantment stemmed in part from his pleasure at sitting in the British Museum Library ‘under the vast dome of the great reading room … where the exile Karl Marx had sat in the 19th century’. The Library was of course a popular haunt of many other 1930s exiles, who often had little money but plenty of time on their hands since employment options were so limited. Regular refugee users of the Library included anthropologist Ernst Bornemann, political activist Margaret Mynatt, and Austrian author Stefan Zweig, in London from 1934 to 1939, who called it ‘die schoenste Bibliothek der Welt’.

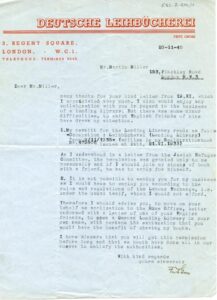

Letter from Fritz Gross to Martin Miller concerning the Deutsche Leihbücherei (German Lending Library) at 3 Regent Square 1940 (EXS/2/GRO/4)

Fritz Gross, 1940 (EXS/2/GRO/3). Photographer: Anneliese Bunyard (by kind permission of Peter Bunyard)

A library of a very different scale, and the opportunity to discuss anti-Nazi activities, brought refugees to 3 Regent Square, in the north of the district. The basement of this house was rented by the political campaigner and pacifist Fritz Gross, who left Germany in 1933 bringing with him his large collection of German-language books. This he used as the basis of a lending library for refugees, gaining official approval from the British authorities to do so in 1935. The flat also served as a meeting point for exiled anti-fascists and other activists, and it was described by Nazi spies at the German Embassy as a central meeting spot for anti-German agitators in London.

Another meeting point for politically-minded refugees thinking ahead to the post-war states to which they would return was the Mary Ward Settlement, which hosted the discussion group ‘Das kommende Österreich’ during 1941. The group stressed the importance of cooperation between all exile groups, but in this case it was the British authorities who were unsettled, suspicious of the group because of its members’ connections with exile Communist groups.

Ten minutes’ walk from the Mary Ward Centre was one of several other Bloomsbury locations associated with the anti-Nazi activists. Socialists Dora Fabian and Mathilde Wurm had left Germany in 1933 to continue in exile with their work to expose the criminal nature of the German regime. They were found dead in the flat they shared in Great Ormond Street in April 1935. The involvement of Nazi agents was suspected by many refugees, and the affair led to extensive discussion in the press and House of Commons about Nazi and anti-Nazi activities in the UK. (The story of Dora Fabian and Mathilde Wurm will be the focus of a talk by Charmian Brinson in October 2021 as part of the Bloomsbury Festival.)

To find out more about this and other sites of historical importance to the refugees, please join us for a free guided tour led by Clare George (Miller Archivist/Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies at the IMLR). Advanced booking is required. Please follow one of the following links to book:

17 June 2021, 11.00am – 12.30pm BST

18 June 2021, 2.00pm – 3.30pm BST

19 June 2021, 11.00am – 12.30pm BST

Those who cannot make the guided walks could instead listen to our audio walk, created for the Being Human Festival in November 2020.

Dr Clare George, Miller Archivist/Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies at the IMLR

Telling the Story of Sport: Narrating Sport in a Global Context

Martin Hurcombe reports on this series of workshops held online during 2020/21, supported by the University of Bristol and the IMLR’s Regional Conference grant scheme

Originally planned as a conference to be held at the University of Bristol, Telling the Story of Sport was one of the first conferences to be cancelled because of the spread of Covid-19. The restrictions placed on international travel paradoxically enabled the organisers to open up the event; by going digital, we really were able to narrate sport in a global context to a global audience. With some trepidation, and after crash courses in a whole range of video-conferencing platforms, the two-day conference was converted into a series of monthly workshops, each with a different theme.

The workshops’ purpose remained that of the conference: to look beyond textual, filmic, pictorial representations of sport purely as source material for sports history and to interrogate the cultural practices that lie behind these diverse narrative practices. These workshops therefore set out to create a series of fora in which scholars could contextualise their research and develop a fuller understanding of the phenomenon of sporting narrative practices across a range of national cultures and scholarly disciplines ranging from Modern Languages to Media Studies via film, history, literature creative practice, and so on.

The sports press has long been the primary resource of many sports historians. Our first workshop, ‘Exploring the role of sports journalism’, featured papers that explored the culture of sports writing. John Hughes presented the seminal work of German exile Willy Meisl in post-war Britain, Ruadhán Cooke discussed the tradition of the suiveur in the Tour de France, and Peter Watson looked at the Colombian press’ construction of the idea of nation during the 1962 football World Cup.

Representing the athletic body was a theme running through several papers across all workshops. ‘Athletic bodies and identities’ in October looked explicitly at the theme in relation to a variety of media and cultural contexts. In his paper, Thomas Campbell drew upon an early boxing periodical to reflect on depictions of race in nineteenth-century England. Race was also discussed in Yann Descamps’ presentation of the representation of basketball in one videogame series. Tanguy Philippe contrasted the depiction of wrestlers in two recent US and Indian films while Jaclyn Meloche explored the politics of bodies in Canadian ice hockey.

‘Sports, memory and identity’ in November featured contributions from Philip Dine on rootedness and relatedness in French sports writing, and an exploration of rural life and nostalgia in two French films (one on rugby and one on football) by Jonathan Ervine, as well as a discussion of a Barry Hines’ script for a football film that was never made, presented by David Forrest.

December’s workshop had a French feel and focused on how gender is conceived, constructed and performed in sporting narratives. Martin Hurcombe thus explored nineteenth-century French masculine, bourgeois identity and its relationship to birth of cycling as a sport. Austin Hancock examined how the French press covered the boxing career of Eugène Criqui following his facial disfigurement during the First World War while Roxanna Curto’s study of Suzanne Lenglen focused on the international tennis star’s representation of her gender.

Tennis also featured in January’s workshop, ‘Creating sporting legacies: processes and identification’. Here John Harris studied the evolving image of Andy Murray in the UK and Scottish media while Yankho Likaku reflected upon the legacy of the football World Cup for South Africa.

‘Space and Place in Sporting Narratives’ was the topic of our February workshop, which was not recorded. Here the focus was on contemporary Russia: Anni Lappela’s explored the function of football in contemporary Russian prose while Seán Crosson read the film Going Vertical (which celebrates the USSR’s 1972 Olympic victory over the USA in basketball) through a contemporary geo-political frame.

Our final workshop recording in March 2021, nearly a year to the day of the planned original conference, was titled ‘Routine unpredictability: narrating everyday football stories in British novels’. The panellists offered a final reminder of the wealth of material that remains to be explored in relation to the cultural history of sport. Dilwyn Porter explored the relationship between Bryan Johnson’s experimental prose (for which he is mostly remembered) with his football coverage in the national press. Literary experimentation and its relationship to the representation of sport was also the theme of Alan McDougall’s study of David Peace’s novel Red or Dead. It was followed by a challenging global sports history quiz which, if it failed to showcase our extensive knowledge of the subject at the end of the workshop series, at least reflected the enjoyment and team-spirit that developed amongst the delegates and speakers over the long months of the pandemic.

Martin Hurcombe, Professor of French Studies, University of Bristol