Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Between Historical Judgement and Identity Politics

Raphael Gross reflects on the issues encountered in planning a new permanent exhibition for Germany’s National History Museum

When I took up the post of Director at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin, it was against a background of debates taking place in the UK and the USA, but also increasingly in Germany, about identity politics. Discussions were already in train at the Museum about its new permanent exhibition to replace the one dating back to 2002, which were, to my surprise, very concerned with the complex question of ‘what is German’. This is not an angle I particularly wish to pursue, but it seems fitting that Germany’s National History Museum should reflect this question in some form.

The old permanent exhibition centred on this question of what is German. The exhibition opened with an image of a forest which, from the Romantic period onwards, has played a prominent part in the culture and historiography of the German-speaking countries, serving as a place of nostalgia, a place in which to connect to national folktales, and as a counterbalance to the city and urbanisation. The question also occupied Richard Wagner, author of Was ist Deutsch, and one of the most influential figures of the nineteenth century, and whose art raises questions as to the connections between music, anti-Semitism and nationalism that continue to be hotly debated, as well as Karl Marx, whose work can be closely linked to German historical events.

The reasons why the old exhibition focused on the question of what is German are interesting, but I feel that the new exhibition should consider how this question relates in particular to twentieth-century history, for example to Auschwitz, and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The presentation of the Holocaust is a challenge for a museum charged with the portrayal of German national history, but at the same time it should not avoid dealing with the concept and history of various forms of German political identity/identities. There is a considerable body of evidence that following 1945, we avoided discussion or creation of a specific national identity because of the Holocaust legacy. Paradoxically, universalising history brings with it the problem of taking responsibility for a specific (German) history, and this is something that a national history museum must address.

Exactly how we will deal with the task is too early to say. The old exhibition closed in June 2021, having only just re-opened following the Covid-19 pandemic. Renovations to the building are expected to take some five years, and in the meanwhile we are planning the new exhibition. Comprising more than one million artefacts and occupying ten thousand square metres in Berlin’s historic Mitte district, the Museum was appropriated by Germany’s rulers in turn and so became a symbolic institution, of which I should like to give a brief tour.

The Museum incorporates the former armoury [Zeughaus] by Carl Traugott Fechhelm in 1785. The giants’ masks by Andreas Schlüter in the central courtyard are Baroque depictions of dying soldiers. In contrast to this compassionate depiction of Germany’s history, there is a picture of Hitler holding a speech in the courtyard in 1943. The occasion is unknown, but it must have been after the Battle of Stalingrad, so the mood of his Nazi following can be assumed to have been somewhat dampened. Walter Ulbricht and Erich Honecker visited the Museum too, then renamed the ‘Museum für Deutsche Geschichte DDR’ when it became the showpiece for the German Democratic Republic. And then there is the modernist annex created by the Sino-American architect I.M.Pei, which provides an interesting foil for the Baroque armoury. Helmut Kohl, a historian himself, took a lively interest both in the Museum and in the annex which he saw as reflecting his vision for a Franco-German alliance at the heart of Europe.

The approach I adopted on taking up the Directorship of the Museum five years ago was not to focus on German identity but rather on historical judgement [historische Urteilskraft], a concept often cited by Hannah Arendt and referring to the capacity to reflect on events of the present in the light of the past. With this in mind, I initiated a number of symposia, exhibitions and publications on the theme, also reflected in the new title of the Museum’s periodical Historische Urteilskraft.

The opening event, held on 7 June 2018, was entitled ‘Die Säule von Cape Cross ̶ Koloniale Objekte und historische Gerechtigkeit’, which attracted an audience of over four hundred, and closed with a discussion on what should be done with one of the Museum’s artefacts. Dating from the fifteenth century, the stone cross had originated in Namibia and, just three weeks after I took up my post, a letter arrived from the Namibian Government requesting its return. I believe the Deutsches Historisches Museum to be the first institution, at least in Germany, to take decisions on the restitution of artefacts acquired during the colonial period on the basis of public discussions which include people from different backgrounds and disciplines, from within and outside the country, rather than being determined by museum staff and lawyers. In May 2019 the Museum’s Board of Trustees unanimously agreed that the cross should be returned.

The following two events focused on the ‘Documenta ̶ Politics and Art’ exhibition, dating back to 1955, and dealing with the relationship between Marx’s and Wagner’s responses to modernity and their individual perceptions of capitalism. Both took part in the 1848/9 Revolution, both were disappointed at its failure, and against a backdrop of industrialisation, both developed their own models of history and society.

‘Historische Urteilskraft’ was a theme also underlying our special exhibitions, so it was appropriate in 2020 to mount an exhibition which was less about Hannah Arendt’s work than about the debates in which she was involved, and we aimed to depict the historical discussion on key topics of twentieth-century history, for example, Jewish emancipation, Zionism, colonialism, racism, Auschwitz, restitution, 1968, and segregation.

Another special exhibition in which I was actively involved was ‘Weimar: Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie’ in 2019, which aimed to show the history of Weimar Germany from the end of the First World War to 1933, when Hitler assumed power, from a different perspective. Against the background of Brexit and Donald Trump’s election as US President, we sought to explore how democracies were coming under increasing pressure, and how they viewed themselves during this period. The collapse of the Weimar Republic was therefore not depicted as a national tragedy, but in terms of the options open to German democrats at the time.

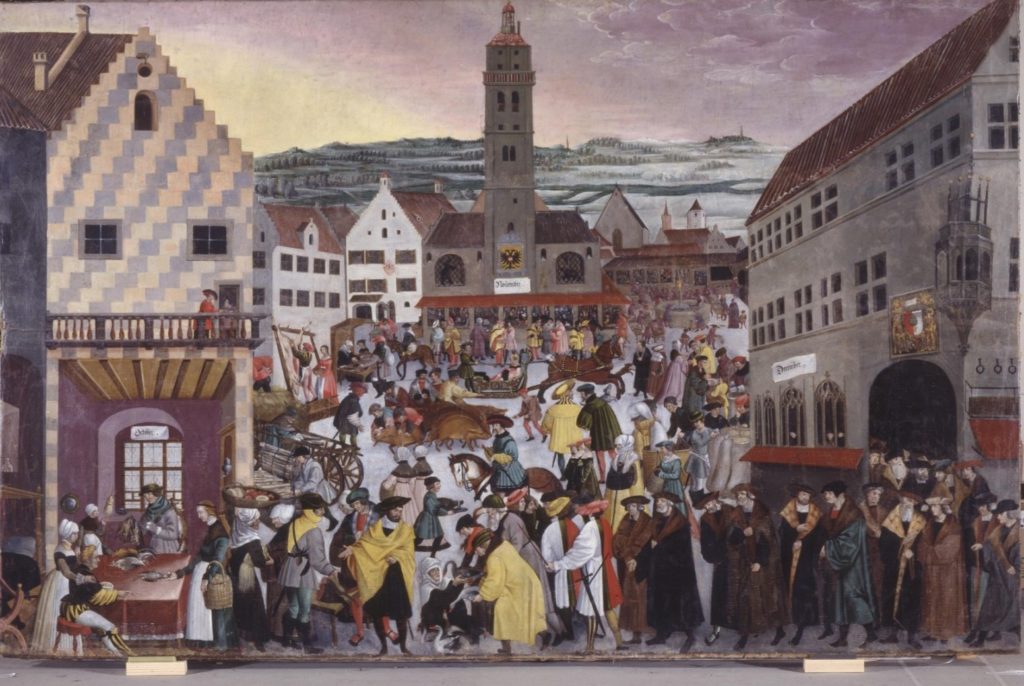

The Museum’s holdings are vast, and one may be forgiven for having some favourites and for considering how they were used in the old exhibition and how they might fit in with the new scheme. For example, the sixteenth-century Augsburger Monatsbilder: Oktober, November, Dezember) give a vivid impression of social structures of the period. Their large-format, highly figurative images depict life and work in Augsburg from season to season, and serve as an inexhaustible source of information on the estate system and how the rulers saw themselves.

There are considerable holdings in the field of medical history, such as the ‘Grüninger Hand’ (a prosthetic arm dating to c. 1505/15) and the ‘Pestmaske’ (Austria/Germany, 1650/1750), which became one of the most visited objects during the pandemic. The Old Armoury holds a huge collection of Prussian weaponry and uniforms, including a hat which once belonged to Napoleon.

The old permanent exhibition included a small section on German colonialism, at the centre of which was a poster (1913) for an ethnological exhibition in the Passage Panopticum entitled ’50 Wilde Kongoweiber, Männer und Kinder in ihrem aufgebauten Kongodorfe’. Its interest lies in how racist and sexist messages were actually emphasised at the time. I believe it was the only female figure of colour in the exhibition, which serves to illustrate how quickly permanent exhibitions date, and that what may have been acceptable twenty years ago certainly is no longer so.

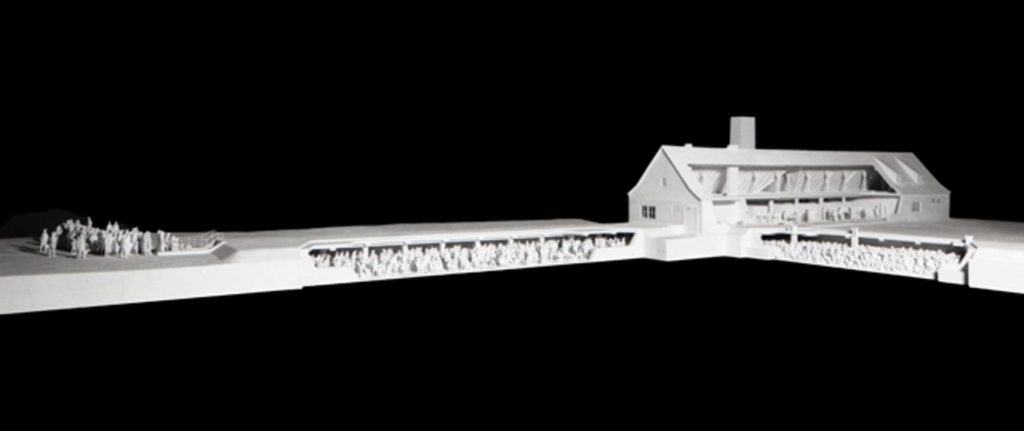

This model of Crematorium II in the Birkenau concentration camp (1995) by the Polish Catholic sculptor Mieczyslaw Stobierski was the focal point of the section on Nazism and the Holocaust, and also featured as part of the Arendt exhibition. It perfectly illustrates Arendt’s description of industrial killing, though I personally think it would be better employed as a depiction of post-war discussion on the nature of the Holocaust rather than as a portrayal of it. Incidentally, in Heidegger’s post-war writing, he refers to ‘the motorised food industry’ and the ‘fabrication of corpses in gas chambers’ as being ‘in essence the same’.

The women’s movement in post-war Germany was accorded little importance when the exhibition was created in 2002, the main exhibit referring to it being a pair of pink-purple dungarees. (An interesting photograph of the exhibit by Annette Kelm hangs in the Foreign Office.) I doubt one would wish to select this as the artefact to reflect this period in German history, though it does indicate how rapidly the discussion around gender issues developed.

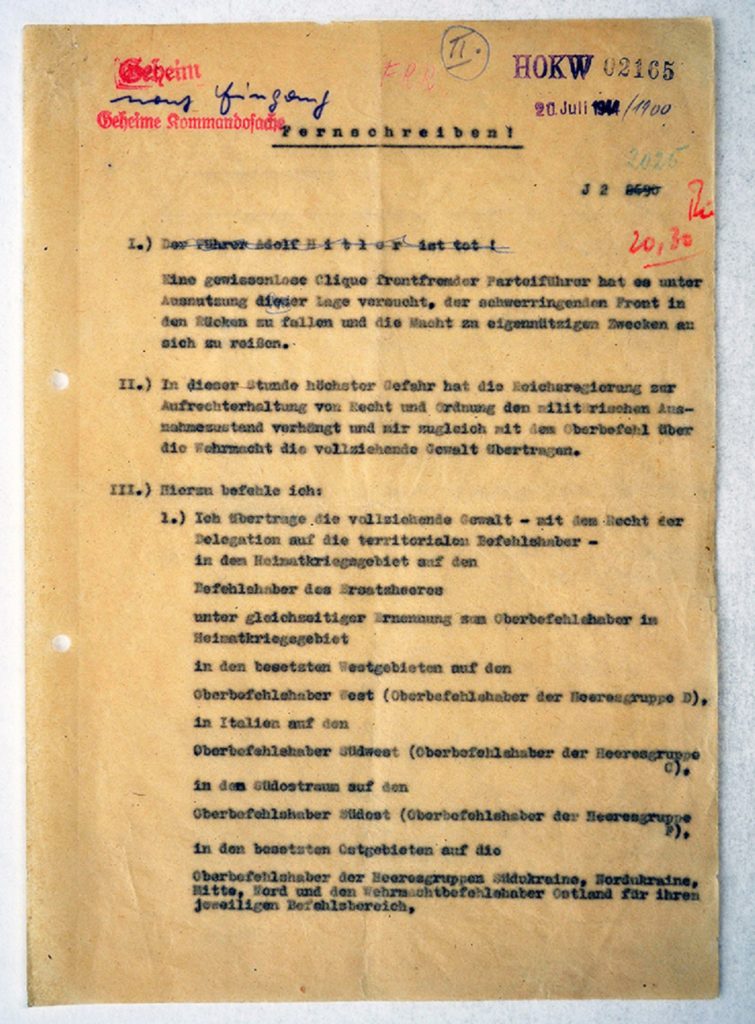

Returning to plans for the new exhibition, we are now considering how we might use artefacts to illustrate how German history might have ‘taken other routes’, a project on which we are working with Dan Diner, the leading Leipzig historian, now based at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. One exhibit one might employ to illustrate this theme is the template for the teleprinter message which would have initiated ‘Operation Valkyre’, modified from an existing plan to ensure the continuity of government in the event of emergency. The first paragraph is headed: ‘Der Führer Adolf Hitler ist tot!’. As is well known, the plot to assassinate Hitler in July 1944 failed, but what if it had succeeded? This provides an opportunity to look back at history and consider how things might have turned out differently, and as such it has something to teach us. If Hitler had died that day, history would have taken a different turn; however, by 1944 the Holocaust had already taken place, and the clock could not be turned back. The teleprinter message therefore represents a pivotal moment in history, but one where the outcome could not have been different.

However, the teleprinter message can be seen as problematic in that it can detract from the actual course of events. So, the main principle which guides our thinking is the depiction of openness in historical development, and specifically how pivotal moments that exemplify that openness can be represented.

The old permanent exhibition closed with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, where the new one will begin. Another difference is that the old exhibition presented unification as an outcome of something long in the making. Willy Brandt’s statement ‘What belongs together grows together’1 has a normative quality to it: children quarrel, then make up. Just like the old exhibition, which presented a narrative as ending as it necessarily had to.

In contrast, we intend presenting the events of 1989 as the product of chance, as a narrator who observes the historical development from afar and who demonstrates that other pathways could have been taken. One might say that the past future is as open as our present time.

1 ‘Jetzt wächst zusammen, was zusammen gehört.’

Images are reproduced here courtesy of the Deutsches Historisches Museum.

Professor Dr Raphael Gross, Deutsches Historisches Museum

Venezuela, Dispersa: A Hybrid Conference, Online and at the University of Exeter

Katie Brown discusses the conference ‘Venezuela, Dispersa‘ held at the University of Exeter on 11 May 2022.

With around 6 million displaced people, the Venezuelan emergency is one of the most significant migratory crises in the contemporary world. While Venezuelans have been emigrating steadily over the last two decades, the relatively recent surge from 2015 onwards has presented a fast-changing landscape that necessitates an interdisciplinary lens to better understand and address the ongoing emergency. Thanks to an IMLR Conference Grant, ‘Venezuela, Dispersa’ brought together researchers from across the humanities, social sciences, medicine and even architecture, as well as representatives of NGOs, to share their work on this urgent topic.

The conference was organised by Dr Rebecca Irons, a medical anthropologist from UCL, and Dr Katie Brown from Exeter, who specialises in Latin American literature. This combination is indicative of range of interests and methodologies covered on the day. Over nine packed hours, twenty-two speakers presented their research methods and findings both in person and online.

We began with a keynote from Cinzia de Santis, CEO of Healing Venezuela, a charity that offers medical assistance to people in Venezuela, including providing medical supplies and sponsoring junior doctors. De Santis gave inspiring examples of the charity’s work and its impact in Venezuela. This was followed by panels on the cultural rights and literary production of Venezuelan migrants; political mobilization, asylum seeking and everyday survival; representation and discourse; access to healthcare (particularly sexual and reproductive care); creativity, work and intersectionality; and oral testimony and autobiography. Throughout we saw examples of quantitative and qualitative methodologies, including creative methodologies such as Photovoice (giving participants cameras to present themselves through photography) or using Whatsapp voicenotes as an archive. The conference ended with a bilingual reading from Inventario para después de la guerra/Inventory for After the War, by Raquel Rivas Rojas, which has just been published by La Joyita Cartonera in Chile. This visceral collection of prose poetry evokes the sounds, tastes, fears, pain and loss experienced in Venezuela.

Participants welcomed the chance to learn about both the findings and methodologies of other researchers, especially as there were clear overlaps (e.g., when similar concerns and language appeared in ethnographic studies and contemporary literature). As Venezuela is still not widely studied, many participants reported working or studying in departments where no one else was familiar with the topic of their research as quite an isolating experience. The conference was therefore a valuable opportunity for collaboration, networking and enriching feedback. Manuel D’Hers, who visited Exeter from Universitat Rovira i Virgili in Tarragona, Spain, noted:

Fue una gran oportunidad de poder compartir con otros compañeros y compañeras sobre Venezuela, reflexionar sobre el país, pero también compartir inquietudes académicas en nuestro proceso de investigar y pensar Venezuela desde nuestras propias experiencias migratorias. Ojalá se repita y volvamos a compartir.

[It was a great opportunity to be able to share with other colleagues about Venezuela, to reflect on the country, but also to share academic concerns in our process of researching and thinking about Venezuela from our own migratory experiences. Hopefully it will be repeated and we will come together again.]

The conference provided emerging researchers with an opportunity to develop their work and gain experience of academic practice. Erick Moreno Superlano, for example, presented his first ever conference paper in preparation for starting an MSc in Migration Studies at Oxford University.

The full conference programme is available online, and a report on the conference was published in the Venezuelan newspaper El Nacional.

Dr Katie Brown, Senior Lecturer in Latin American Studies, University of Exeter

Emigration Diaries: Refugee Lives between the Ordinary and the Exceptional

Kathryn Sederberg, Assistant Professor of German Studies, Kalamazoo College, USA

Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Visiting Fellow, June 2022

In the 1930s, as Jewish Germans and Austrians fled their homes in search of safety, many of them kept diaries: young and old, men and women, in bound books and on loose-leaf paper. Just as those persecuted by the Nazis ended up all over the world—from Ecuador to New York to London to Shanghai—so, too, are their accounts now scattered in archives around the world, everywhere refugees found a new home. In my current project, I consider the motivations for keeping a diary during emigration, the changing role of diary writing as a practice, and the ways Jewish refugees wrote themselves into various autobiographical traditions. Although many exiles would later put pen to paper and write their memoirs, I consider what it means to write a narrative of emigration during forced migration and resettlement, and to construct the self as a refugee in the pages of a diary.

In contrast to memoirs, which are constructed retrospectively and given narrative coherence, diaries provide evidence of both the banalities of day-to-day life, and events of world-historical importance. The juxtaposition of the banal and the extraordinary demonstrate the way individuals continue their daily lives even through traumatic experiences. In this blog post, I highlight an example from the collections of the Exile Archive at the IMLR that demonstrates the way one refugee from National Socialism used diary writing, and the way her text addresses past, present, and future.

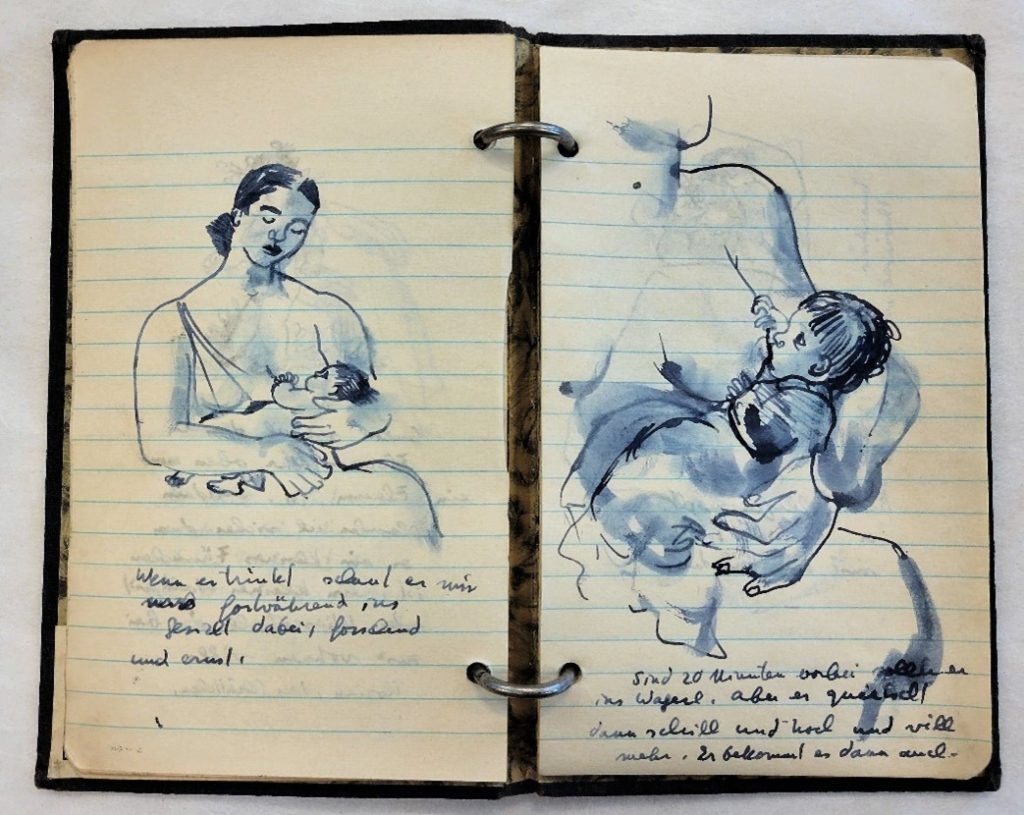

Austrian artist Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag, born 1902 in Vienna, emigrated first to Palestine in 1934, and then to London in December 1935, where she was later joined by her husband, the architect Josef Berger. She was a visual artist, designer, and author who continued her career in England. Among her papers are several journals and diary-like accounts from different periods of her life, including a diary she began for her son Florian (later called Raymond) in January 1938, which she continued until May 1938. Parent or baby diaries (Elterntagebücher) were a common practice in twentieth-century Germany and Austria. However, this diary is unique because of the hand-drawn artwork, the enclosed photographs, and the way that the diary simultaneously bears witness to new motherhood and the experiences of a refugee family forging a life in a new country.

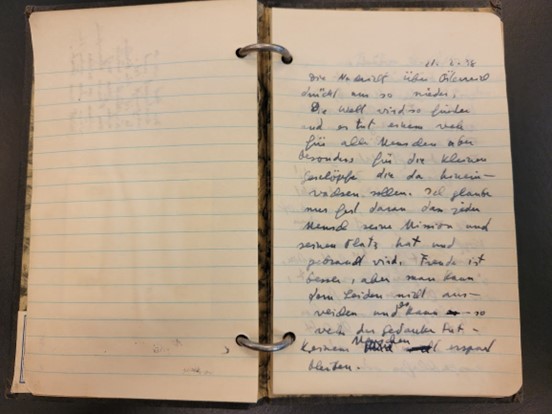

Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag begins the diary, a small black, two-ring binder with loose-leaf, lined pages, in early 1938. At this point, she has been in England just over two years. She writes in German, describing the birth of her son, the first sight of his small, bluish body, and her adjustment to motherhood. She reflects on the changes in her own body and mind, and her desire to regain a sense of self and independence after a difficult pregnancy. In the pages of this diary, she wonders, ‘Who am I at this moment…?’ (Wer bin ich in diesem Moment…?) She writes that she feels herself growing into a ‘new, fresh self’ (ein neues, frisches ich). As we see here, although the motivation for beginning this journal is the birth of her son, this milestone in her life also prompts reflection on her changing sense of identity, and the diary includes self-portraits as well as ink drawings of her son (see Figure 1).

Although the development of her son is the primary topic in the diary, the text also bears witness to the political situation of the late 1930s. Berger-Hamerschlag writes at regular intervals during these first few months of Florian’s life, noting changes in his diet, his first smile, and tracking his weight. However, on February 21, 1938, she interrupts this family account with troubling news from home (see Figure 2):

The news about Austria makes us so depressed. The world is getting so gloomy and it pains you for everyone but especially for the little ones who are supposed to grow up in it. I just strongly believe that everyone has his mission and his place and is needed. Joy is better, but you can’t avoid suffering and – although it’s a painful thought – no one is spared from it.

Die Nachricht über Österreich drückt uns so nieder. Die Welt wird so düster und es tut einem weh für alle Menschen aber besonders für die kleinen Geschöpfe die da hineinwachsen sollen. Ich glaube nur fest daran, dass jeder Mensch seine Mission und seinen Platz hat und gebraucht wird. Freude ist besser, aber man kann dem Leiden nicht ausweichen und es kann – so weh der Gedanken tut – keinem Menschen erspart bleiben.

After the birth of her son, Berger-Hamerschlag sees political events through a new lens, thinking of her baby who will grow up in a very different world. She continues this entry with the positive news: ‘I am painting again’ (Ich male wieder). This blend of topics is characteristic of the diary as an autobiographical form, and reflects a life narrative still being constructed, and a self in flux.

In the few months of writing, political events continue to interrupt Berger-Hamerschlag’s diary, for example in an entry written days after the Anschluss of Austria in March 1938. First, she begins by noting baby Florian’s new diet, the ‘new, thicker milk mixture,’ and the solid foods they are giving him. Then she abruptly pivots: ‘What kind of world is this little boy born into! […] It seems to me that the world is collapsing, I can’t free myself from this feeling for even a minute.’ (In was für eine Welt ist dieses Bübchen geboren! […] Mir ist als ob die Welt unterginge, ich kann mich keine Minute von diesem Gefühl befreien.) Her loving attention to the development of her son and her joy is overshadowed by the news from Austria. On March 27, she comments again on the political context, reflecting on the spread of racist, antisemitic, and militaristic ideology:

Life could be so good for everyone. There are a few crazy people who say “the N***” the ‘fascists’ ‘the Bolsheviks,’ ‘the Jews’, ‘the -ists, -ists etc.’ And other crazies follow them and all the money that one should use for the happiness of humanity is spent for their unhappiness, for weapons. It seems hopelessly crazy. Today he is 14/13 lb.

Das Leben könnte doch so gut für alle sein. Da sind ein paar Irrsinnige die sagen „die N****“ die „Fascisten“ „die Bolscheviken“, „die Juden“ „die isten, isten etc“ und andere Irre folgen ihnen und alles Geld das man für das Glück der Menschheit verwenden müsste wird für ihr Unglück, für Waffen, ausgeben. Es sieht hoffnungslos verrückt aus. Heute hat er 14/13 lb.

This entry is exemplary for the tension within diary entries between the mundane and the exceptional, the personal and the political. Although this diary is focused on what is happening in Europe, the entry ends with her baby’s weight. The markers of her son’s growth are a way of recentering, shifting her focus from the world political events to the baby in her lap.

In general, we might consider this small diary to be a typical account of a baby’s first few months, and a mother focused on documenting her son’s milestones. Additionally, this diary as a material object should be considered an important artifact of a life of an exile in London. On the one hand, Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag strives to find a new sense of self as a young mother and artist. On the other hand, her observations about her son and her self are punctuated by world-historical events which continually disrupt her new life, and are a source of worry and a constant background to what is happening in her day-to-day life. The diary reflects the author’s need to express herself, to reflect on the changes in her own life, and that of her son. Yet keeping this diary should be read as an inherently optimistic gesture as she considers the life she is giving and building for her son. She writes for her son’s future, creating a bank of memories of this moment: early 1939 through the eyes of refugee, mother, and artist.

The papers of Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag are in the Senate House Library collections. A catalogue is available online. Thank you to archivist Clare George for her assistance during my visit to London. Translations above are from the author.

Kathryn Sederberg, Assistant Professor of German Studies, Kalamazoo College, USA

Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Visiting Fellow, June 2022