Kathryn Sederberg, Assistant Professor of German Studies, Kalamazoo College, USA

Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Visiting Fellow, June 2022

In the 1930s, as Jewish Germans and Austrians fled their homes in search of safety, many of them kept diaries: young and old, men and women, in bound books and on loose-leaf paper. Just as those persecuted by the Nazis ended up all over the world—from Ecuador to New York to London to Shanghai—so, too, are their accounts now scattered in archives around the world, everywhere refugees found a new home. In my current project, I consider the motivations for keeping a diary during emigration, the changing role of diary writing as a practice, and the ways Jewish refugees wrote themselves into various autobiographical traditions. Although many exiles would later put pen to paper and write their memoirs, I consider what it means to write a narrative of emigration during forced migration and resettlement, and to construct the self as a refugee in the pages of a diary.

In contrast to memoirs, which are constructed retrospectively and given narrative coherence, diaries provide evidence of both the banalities of day-to-day life, and events of world-historical importance. The juxtaposition of the banal and the extraordinary demonstrate the way individuals continue their daily lives even through traumatic experiences. In this blog post, I highlight an example from the collections of the Exile Archive at the IMLR that demonstrates the way one refugee from National Socialism used diary writing, and the way her text addresses past, present, and future.

Austrian artist Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag, born 1902 in Vienna, emigrated first to Palestine in 1934, and then to London in December 1935, where she was later joined by her husband, the architect Josef Berger. She was a visual artist, designer, and author who continued her career in England. Among her papers are several journals and diary-like accounts from different periods of her life, including a diary she began for her son Florian (later called Raymond) in January 1938, which she continued until May 1938. Parent or baby diaries (Elterntagebücher) were a common practice in twentieth-century Germany and Austria. However, this diary is unique because of the hand-drawn artwork, the enclosed photographs, and the way that the diary simultaneously bears witness to new motherhood and the experiences of a refugee family forging a life in a new country.

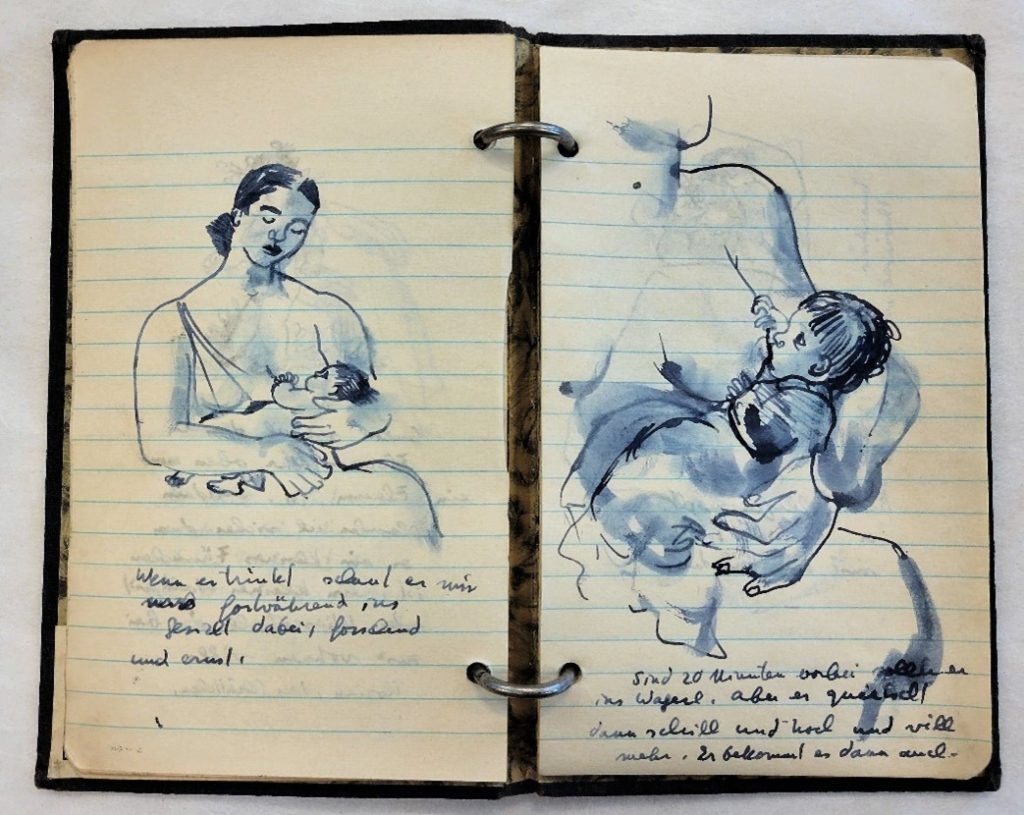

Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag begins the diary, a small black, two-ring binder with loose-leaf, lined pages, in early 1938. At this point, she has been in England just over two years. She writes in German, describing the birth of her son, the first sight of his small, bluish body, and her adjustment to motherhood. She reflects on the changes in her own body and mind, and her desire to regain a sense of self and independence after a difficult pregnancy. In the pages of this diary, she wonders, ‘Who am I at this moment…?’ (Wer bin ich in diesem Moment…?) She writes that she feels herself growing into a ‘new, fresh self’ (ein neues, frisches ich). As we see here, although the motivation for beginning this journal is the birth of her son, this milestone in her life also prompts reflection on her changing sense of identity, and the diary includes self-portraits as well as ink drawings of her son (see Figure 1).

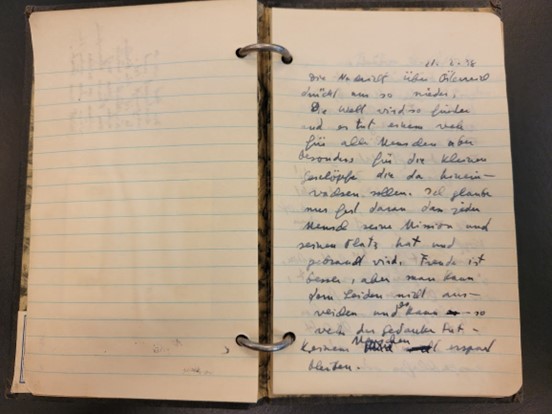

Although the development of her son is the primary topic in the diary, the text also bears witness to the political situation of the late 1930s. Berger-Hamerschlag writes at regular intervals during these first few months of Florian’s life, noting changes in his diet, his first smile, and tracking his weight. However, on February 21, 1938, she interrupts this family account with troubling news from home (see Figure 2):

The news about Austria makes us so depressed. The world is getting so gloomy and it pains you for everyone but especially for the little ones who are supposed to grow up in it. I just strongly believe that everyone has his mission and his place and is needed. Joy is better, but you can’t avoid suffering and – although it’s a painful thought – no one is spared from it.

Die Nachricht über Österreich drückt uns so nieder. Die Welt wird so düster und es tut einem weh für alle Menschen aber besonders für die kleinen Geschöpfe die da hineinwachsen sollen. Ich glaube nur fest daran, dass jeder Mensch seine Mission und seinen Platz hat und gebraucht wird. Freude ist besser, aber man kann dem Leiden nicht ausweichen und es kann – so weh der Gedanken tut – keinem Menschen erspart bleiben.

After the birth of her son, Berger-Hamerschlag sees political events through a new lens, thinking of her baby who will grow up in a very different world. She continues this entry with the positive news: ‘I am painting again’ (Ich male wieder). This blend of topics is characteristic of the diary as an autobiographical form, and reflects a life narrative still being constructed, and a self in flux.

In the few months of writing, political events continue to interrupt Berger-Hamerschlag’s diary, for example in an entry written days after the Anschluss of Austria in March 1938. First, she begins by noting baby Florian’s new diet, the ‘new, thicker milk mixture,’ and the solid foods they are giving him. Then she abruptly pivots: ‘What kind of world is this little boy born into! […] It seems to me that the world is collapsing, I can’t free myself from this feeling for even a minute.’ (In was für eine Welt ist dieses Bübchen geboren! […] Mir ist als ob die Welt unterginge, ich kann mich keine Minute von diesem Gefühl befreien.) Her loving attention to the development of her son and her joy is overshadowed by the news from Austria. On March 27, she comments again on the political context, reflecting on the spread of racist, antisemitic, and militaristic ideology:

Life could be so good for everyone. There are a few crazy people who say “the N***” the ‘fascists’ ‘the Bolsheviks,’ ‘the Jews’, ‘the -ists, -ists etc.’ And other crazies follow them and all the money that one should use for the happiness of humanity is spent for their unhappiness, for weapons. It seems hopelessly crazy. Today he is 14/13 lb.

Das Leben könnte doch so gut für alle sein. Da sind ein paar Irrsinnige die sagen „die N****“ die „Fascisten“ „die Bolscheviken“, „die Juden“ „die isten, isten etc“ und andere Irre folgen ihnen und alles Geld das man für das Glück der Menschheit verwenden müsste wird für ihr Unglück, für Waffen, ausgeben. Es sieht hoffnungslos verrückt aus. Heute hat er 14/13 lb.

This entry is exemplary for the tension within diary entries between the mundane and the exceptional, the personal and the political. Although this diary is focused on what is happening in Europe, the entry ends with her baby’s weight. The markers of her son’s growth are a way of recentering, shifting her focus from the world political events to the baby in her lap.

In general, we might consider this small diary to be a typical account of a baby’s first few months, and a mother focused on documenting her son’s milestones. Additionally, this diary as a material object should be considered an important artifact of a life of an exile in London. On the one hand, Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag strives to find a new sense of self as a young mother and artist. On the other hand, her observations about her son and her self are punctuated by world-historical events which continually disrupt her new life, and are a source of worry and a constant background to what is happening in her day-to-day life. The diary reflects the author’s need to express herself, to reflect on the changes in her own life, and that of her son. Yet keeping this diary should be read as an inherently optimistic gesture as she considers the life she is giving and building for her son. She writes for her son’s future, creating a bank of memories of this moment: early 1939 through the eyes of refugee, mother, and artist.

The papers of Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag are in the Senate House Library collections. A catalogue is available online. Thank you to archivist Clare George for her assistance during my visit to London. Translations above are from the author.

Kathryn Sederberg, Assistant Professor of German Studies, Kalamazoo College, USA

Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Visiting Fellow, June 2022