Raphael Gross reflects on the issues encountered in planning a new permanent exhibition for Germany’s National History Museum

When I took up the post of Director at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin, it was against a background of debates taking place in the UK and the USA, but also increasingly in Germany, about identity politics. Discussions were already in train at the Museum about its new permanent exhibition to replace the one dating back to 2002, which were, to my surprise, very concerned with the complex question of ‘what is German’. This is not an angle I particularly wish to pursue, but it seems fitting that Germany’s National History Museum should reflect this question in some form.

The old permanent exhibition centred on this question of what is German. The exhibition opened with an image of a forest which, from the Romantic period onwards, has played a prominent part in the culture and historiography of the German-speaking countries, serving as a place of nostalgia, a place in which to connect to national folktales, and as a counterbalance to the city and urbanisation. The question also occupied Richard Wagner, author of Was ist Deutsch, and one of the most influential figures of the nineteenth century, and whose art raises questions as to the connections between music, anti-Semitism and nationalism that continue to be hotly debated, as well as Karl Marx, whose work can be closely linked to German historical events.

The reasons why the old exhibition focused on the question of what is German are interesting, but I feel that the new exhibition should consider how this question relates in particular to twentieth-century history, for example to Auschwitz, and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The presentation of the Holocaust is a challenge for a museum charged with the portrayal of German national history, but at the same time it should not avoid dealing with the concept and history of various forms of German political identity/identities. There is a considerable body of evidence that following 1945, we avoided discussion or creation of a specific national identity because of the Holocaust legacy. Paradoxically, universalising history brings with it the problem of taking responsibility for a specific (German) history, and this is something that a national history museum must address.

Exactly how we will deal with the task is too early to say. The old exhibition closed in June 2021, having only just re-opened following the Covid-19 pandemic. Renovations to the building are expected to take some five years, and in the meanwhile we are planning the new exhibition. Comprising more than one million artefacts and occupying ten thousand square metres in Berlin’s historic Mitte district, the Museum was appropriated by Germany’s rulers in turn and so became a symbolic institution, of which I should like to give a brief tour.

The Museum incorporates the former armoury [Zeughaus] by Carl Traugott Fechhelm in 1785. The giants’ masks by Andreas Schlüter in the central courtyard are Baroque depictions of dying soldiers. In contrast to this compassionate depiction of Germany’s history, there is a picture of Hitler holding a speech in the courtyard in 1943. The occasion is unknown, but it must have been after the Battle of Stalingrad, so the mood of his Nazi following can be assumed to have been somewhat dampened. Walter Ulbricht and Erich Honecker visited the Museum too, then renamed the ‘Museum für Deutsche Geschichte DDR’ when it became the showpiece for the German Democratic Republic. And then there is the modernist annex created by the Sino-American architect I.M.Pei, which provides an interesting foil for the Baroque armoury. Helmut Kohl, a historian himself, took a lively interest both in the Museum and in the annex which he saw as reflecting his vision for a Franco-German alliance at the heart of Europe.

The approach I adopted on taking up the Directorship of the Museum five years ago was not to focus on German identity but rather on historical judgement [historische Urteilskraft], a concept often cited by Hannah Arendt and referring to the capacity to reflect on events of the present in the light of the past. With this in mind, I initiated a number of symposia, exhibitions and publications on the theme, also reflected in the new title of the Museum’s periodical Historische Urteilskraft.

The opening event, held on 7 June 2018, was entitled ‘Die Säule von Cape Cross ̶ Koloniale Objekte und historische Gerechtigkeit’, which attracted an audience of over four hundred, and closed with a discussion on what should be done with one of the Museum’s artefacts. Dating from the fifteenth century, the stone cross had originated in Namibia and, just three weeks after I took up my post, a letter arrived from the Namibian Government requesting its return. I believe the Deutsches Historisches Museum to be the first institution, at least in Germany, to take decisions on the restitution of artefacts acquired during the colonial period on the basis of public discussions which include people from different backgrounds and disciplines, from within and outside the country, rather than being determined by museum staff and lawyers. In May 2019 the Museum’s Board of Trustees unanimously agreed that the cross should be returned.

The following two events focused on the ‘Documenta ̶ Politics and Art’ exhibition, dating back to 1955, and dealing with the relationship between Marx’s and Wagner’s responses to modernity and their individual perceptions of capitalism. Both took part in the 1848/9 Revolution, both were disappointed at its failure, and against a backdrop of industrialisation, both developed their own models of history and society.

‘Historische Urteilskraft’ was a theme also underlying our special exhibitions, so it was appropriate in 2020 to mount an exhibition which was less about Hannah Arendt’s work than about the debates in which she was involved, and we aimed to depict the historical discussion on key topics of twentieth-century history, for example, Jewish emancipation, Zionism, colonialism, racism, Auschwitz, restitution, 1968, and segregation.

Another special exhibition in which I was actively involved was ‘Weimar: Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie’ in 2019, which aimed to show the history of Weimar Germany from the end of the First World War to 1933, when Hitler assumed power, from a different perspective. Against the background of Brexit and Donald Trump’s election as US President, we sought to explore how democracies were coming under increasing pressure, and how they viewed themselves during this period. The collapse of the Weimar Republic was therefore not depicted as a national tragedy, but in terms of the options open to German democrats at the time.

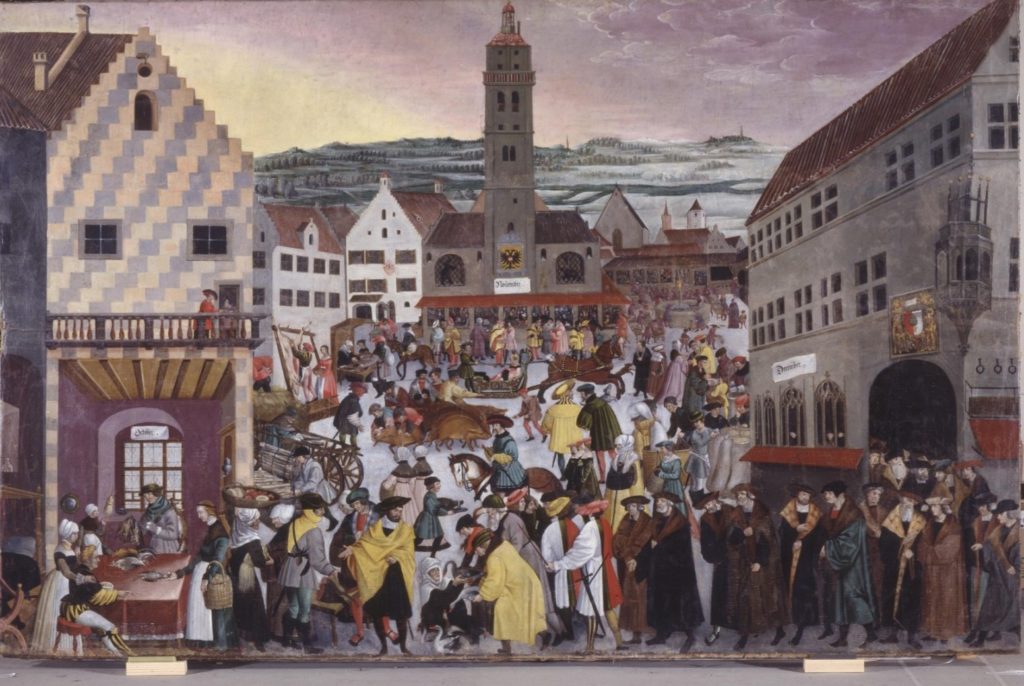

The Museum’s holdings are vast, and one may be forgiven for having some favourites and for considering how they were used in the old exhibition and how they might fit in with the new scheme. For example, the sixteenth-century Augsburger Monatsbilder: Oktober, November, Dezember) give a vivid impression of social structures of the period. Their large-format, highly figurative images depict life and work in Augsburg from season to season, and serve as an inexhaustible source of information on the estate system and how the rulers saw themselves.

There are considerable holdings in the field of medical history, such as the ‘Grüninger Hand’ (a prosthetic arm dating to c. 1505/15) and the ‘Pestmaske’ (Austria/Germany, 1650/1750), which became one of the most visited objects during the pandemic. The Old Armoury holds a huge collection of Prussian weaponry and uniforms, including a hat which once belonged to Napoleon.

The old permanent exhibition included a small section on German colonialism, at the centre of which was a poster (1913) for an ethnological exhibition in the Passage Panopticum entitled ’50 Wilde Kongoweiber, Männer und Kinder in ihrem aufgebauten Kongodorfe’. Its interest lies in how racist and sexist messages were actually emphasised at the time. I believe it was the only female figure of colour in the exhibition, which serves to illustrate how quickly permanent exhibitions date, and that what may have been acceptable twenty years ago certainly is no longer so.

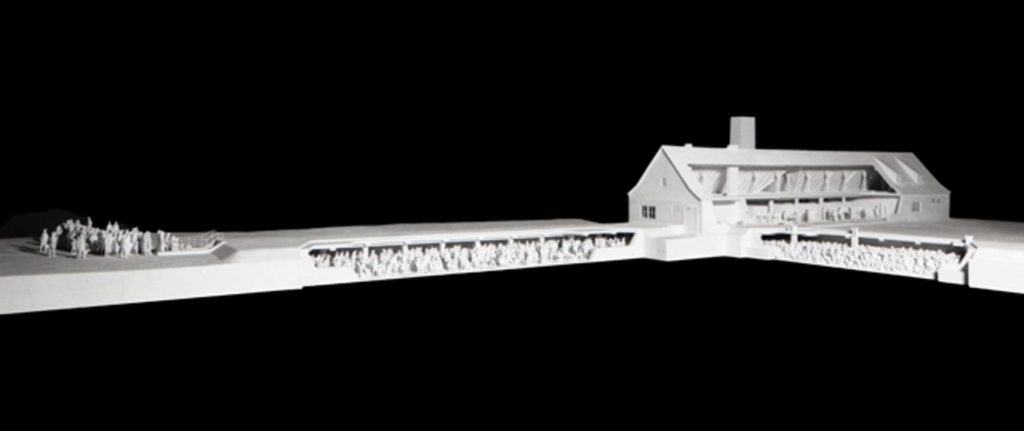

This model of Crematorium II in the Birkenau concentration camp (1995) by the Polish Catholic sculptor Mieczyslaw Stobierski was the focal point of the section on Nazism and the Holocaust, and also featured as part of the Arendt exhibition. It perfectly illustrates Arendt’s description of industrial killing, though I personally think it would be better employed as a depiction of post-war discussion on the nature of the Holocaust rather than as a portrayal of it. Incidentally, in Heidegger’s post-war writing, he refers to ‘the motorised food industry’ and the ‘fabrication of corpses in gas chambers’ as being ‘in essence the same’.

The women’s movement in post-war Germany was accorded little importance when the exhibition was created in 2002, the main exhibit referring to it being a pair of pink-purple dungarees. (An interesting photograph of the exhibit by Annette Kelm hangs in the Foreign Office.) I doubt one would wish to select this as the artefact to reflect this period in German history, though it does indicate how rapidly the discussion around gender issues developed.

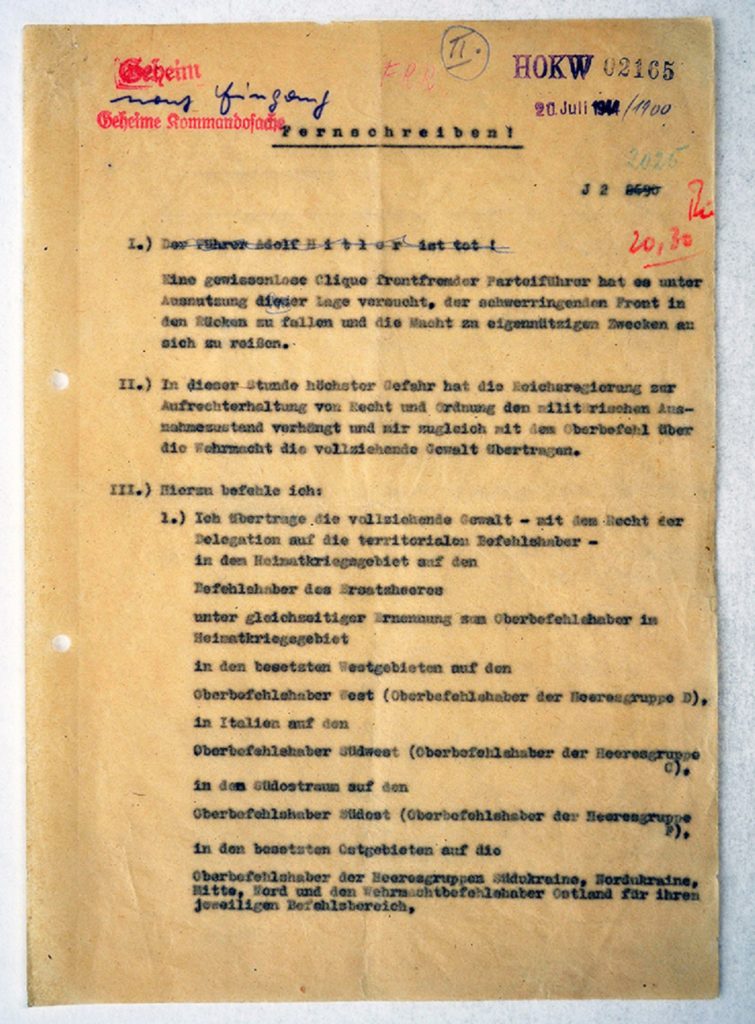

Returning to plans for the new exhibition, we are now considering how we might use artefacts to illustrate how German history might have ‘taken other routes’, a project on which we are working with Dan Diner, the leading Leipzig historian, now based at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. One exhibit one might employ to illustrate this theme is the template for the teleprinter message which would have initiated ‘Operation Valkyre’, modified from an existing plan to ensure the continuity of government in the event of emergency. The first paragraph is headed: ‘Der Führer Adolf Hitler ist tot!’. As is well known, the plot to assassinate Hitler in July 1944 failed, but what if it had succeeded? This provides an opportunity to look back at history and consider how things might have turned out differently, and as such it has something to teach us. If Hitler had died that day, history would have taken a different turn; however, by 1944 the Holocaust had already taken place, and the clock could not be turned back. The teleprinter message therefore represents a pivotal moment in history, but one where the outcome could not have been different.

However, the teleprinter message can be seen as problematic in that it can detract from the actual course of events. So, the main principle which guides our thinking is the depiction of openness in historical development, and specifically how pivotal moments that exemplify that openness can be represented.

The old permanent exhibition closed with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, where the new one will begin. Another difference is that the old exhibition presented unification as an outcome of something long in the making. Willy Brandt’s statement ‘What belongs together grows together’1 has a normative quality to it: children quarrel, then make up. Just like the old exhibition, which presented a narrative as ending as it necessarily had to.

In contrast, we intend presenting the events of 1989 as the product of chance, as a narrator who observes the historical development from afar and who demonstrates that other pathways could have been taken. One might say that the past future is as open as our present time.

1 ‘Jetzt wächst zusammen, was zusammen gehört.’

Images are reproduced here courtesy of the Deutsches Historisches Museum.

Professor Dr Raphael Gross, Deutsches Historisches Museum