Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

The Positive Impact of Digital Homelands on the Language Revitalisation of Diasporic Languages: the Case of Ladino

Carlos Yebra López reflects on the revitalisation of Ladino made possible through online communities. This is discussed more fully in the video included below and was also the focus of a conference held at the IMLR in 2019

By virtue of their nature, diasporic languages often lack a unified geographical territory, which prevents their intergenerational transmission. However, in recent decades there has been a significant trend in the emergence of digital homelands (Held, 2010), ie, virtual communities where the diasporic language in question is used as the only means of communication between users.

According to Held, virtual communities are not just mere spaces for communication. Rather, they have the potential to become “a territory where a culture may be revitalised after having faced a state of severe decline”, which has also been referred to as a “kingdom of the word” (Shandler, 2004), or “a national language of nowhere” (idem).

This contemporary trend is crucial for the purpose of reversing language shift, as it fulfills the two key conditions envisaged by sociolinguist Joshua Fishman (1991) for the purpose of effectively countering language attrition: intergenerational transmission and diglossic, functional isolation.

In my presentation for The Language Event in Edinburgh earlier this year, I applied this theoretical background to the case of a minoritised and diasporic language by the name of Ladino, which has been classified by UNESCO as an endangered language. Ladino, also called Judeo-Spanish, Judezmo or Espanyolit, is the language spoken by Jewish people whose ancestors lived in the Iberian Peninsula until their expulsion at the end of the 15th century. Although Ladino was shaped in diaspora, mostly in the Eastern Mediterranean, it preserves a great deal from the linguistic varieties spoken in medieval Iberia, which helps explain its deceiving similarity with Castilian Spanish.

In particular, I discussed three case studies of Ladino-only online communities: the email list Ladinokomunita (1999-), the initiative Ladino Forever (Halphie, 2016-), and the digital archive Ladino 21 (Yebra, Acero, Aguado, 2017-).

Watch the talk online here:

Dr Carlos Yebra López, New York University

Self-Isolation in the Time of Plague

Anne Simon reflects on self-isolating in the 16th century, with comparisons to today’s situation in the time of COVID-19

As a nun Katerina Lemmel (1466-1533) was, of course, used to self-isolating, although that had not always been the case. Born into one of the wealthiest, most powerful merchant families in late-medieval Nuremberg, she was accustomed to the hustle and bustle of the city’s business, cultural and intellectual life. Nuremberg, one of the richest, politically most important cities in the Holy Roman Empire and a leading financial market of the age, stood at the crossroads of numerous trade routes which stretched across Europe from London to Russia to Sicily to Scandinavia to Poland to Spain ‒ and even further afield to Alexandria, India and, via Lisbon, the New World. A main source of the city’s wealth was the all-important spice trade: pepper was more valuable than gold, and Nuremberg held the monopoly on the most precious spice of all, saffron. The city was also famous for metal goods, tools, clocks and scientific instruments (nautical, surgical, astronomical). Trade brought news and information (Luther called the city ‘das Auge und Ohr Deutschlands’), openness to intellectual currents and new ideas (Nuremberg was an early centre of Humanism), and the wealth to support artists of the calibre of Albrecht Dürer, Michael Wolgemut, Veit Stoß, Veit Hirsvogel and Adam Kraft. Katerina Lemmel herself had been a successful businesswoman, investing in property, mining, agriculture and viticulture. When, on the death of her husband, she left this world behind to become a Birgittine nun at the convent of Maria Mai in Maihingen in 1516, her life changed radically. Of course, relocating for religious reasons is not quite the same as celebrity self-isolation in Cornwall or the Caribbean, but there are some similarities to the current situation.

Maihingen, a small village six miles from Nördlingen (Bavaria) and fifty-seven from Nuremberg, was rural and remote. These days a quick drive down the B466 from Nuremberg gets you there in roughly an hour and twenty minutes, but in the early sixteenth century the journey took several days. Maria Mai was a small, poor foundation, in such architectural disrepair that rainwater dripped into the sisters’ cells, and a far cry from the web of trade, family and comfort to which Katerina Lemmel had been used. She obviously suffered under the separation from her family: in her letters, written from the convent to her cousin Hans V Imhoff, head of the Imhoff family trading company, between 1516 and 1525, she frequently expresses her disappointment at her family’s failure to visit her.[1] The Birgittines were an enclosed order, so once Katerina had taken vows she was not permitted to leave the convent. Communication was also far from straightforward: no email, Skype, Zoom or any of the other electronic possibilities for keeping in touch with family and friends in the age of Covid-19; and the Thurn und Taxis postal service set up in the Holy Roman Empire by Franz von Taxis was still in its earliest infancy. Mail was transported by (not always reliable) messenger and subject to loss or delay: ‘We send them [letters] to Oettingen, to Keterlein the innkeeper; she gives them to the messengers from the city of Ulm or to a wagon driver from Ulm or Nördlingen. […] With the letters that were lost, it was our servant who gave them to the son of Frau Hans Fugger at the fair in Nördlingen’ (Letter, 26 September 1517).

Even when the hurdles to communication were overcome, obtaining food and medicine was a further problem. While hand sanitizer was not sought after and flour seems to have been readily available, Katerina’s letters to her cousin are full of requests for basic provisions either not grown locally or in short supply due to poor harvests: rice, oil, millet, raisins, salted fish, split peas, almonds, and, above all, pepper and spices. Crucial for the flavouring and preservation of food (research at Cornell University has shown spices possess anti-microbial properties which decelerate decay),[2] spices did not just enhance a monotonous diet, but were used medicinally. Saffron, for example, rich in vitamins A, B and C, had long been used as a cure for wounds, coughs, colic, headaches and the plague; in the treatment of the liver, eyes, throat and mouth; and as a treatment for depression, being a known mood- and even performance-enhancer.[3] Katerina justifies one request to her long-suffering cousin with the remark: ‘One does need to spice things up a bit, especially when the men and the sisters have to sing and pray a lot’ (26 September 1517). Similarly, beer and wine, far from being a comforting escape from pandemic-induced panic, were needed for nutrition and strength, not least for the daily performance of the eight Divine Offices: ‘They [the monks and nuns at Maria Mai] must drink beer during this time of great singing and reading’ (19 February 1518). However, wine especially was not always easy to obtain: there was no quick trip to Waitrose or Majestic. The poverty of the convent, and later the destruction of convent-owned vineyards in Württemberg during Reformation unrest, meant supplies were disrupted: ‘Now on many days the sisters don’t get even a drop of wine — only those who are weak receive some’ (23 October 1517).

Then there was the Plague. Originating in Central or East Asia, it reached Europe in 1347, brought by fleas on rats on Genoese merchant ships returning from the Crimea. It killed somewhere between 75 and 200 million people, recurring sporadically across Europe for over 300 years and causing religious, social and economic upheaval. [4] At the time its causes were unknown, so the Plague was variously blamed on an unfavourable conjunction of planets, noxious emanations from the earth, the weather, sick livestock, a pestilence-breathing giant who stalked the land (but not on 5G!). Katerina mentions the Plague and other epidemics in her letters, her thoughts going to her family in Nuremberg, vulnerable due to the city’s dense population, high number of visitors from abroad and even its own merchants returning home from pilgrimages or business trips.[5] While the wealthy could take refuge in their country retreats ‒ some affluent Nuremberg families already owned houses in the surrounding territories ‒ the poor were worse affected, including in the villages around Maria Mai. In a letter dated 19 February 1518, Katerina mentions eight children orphaned by their parents’ death from the pestilence. Although isolated in the depths of rural Bavaria, the convent’s religious duty of charity and care for the poor and sick meant the nuns were, in practice, exposed to risk on more or less a daily basis. Katerina ‒ who had lost her sister Felicitas to an earlier outbreak of the Plague ‒ sends her family the only remedy she knows: ‘So I send [. . .] you each a little pomander. This is how they grow around here, with aromatic seeds. The fragrance is supposed to be good for warding off the bad vapors, and on it, in the quill of a feather, are the tau sign and many devotional words, which one should have on one’s person at the time of death. […] May it please our dear Lord to be gracious and merciful to us all!’ (21 January 1518).

Dr Anne Simon, Associate Fellow IMLR

[1] The letters are a rich source for the lived reality not just of late-medieval monasticism, but also trade, artistic patronage, finance, transport, women’s networks and more: Pepper for Prayer: The Correspondence of the Birgittine Nun Katerina Lemmel, 1516‒1525, ed. and trans. by Volker Schier, Corine Schleif and Anne Simon (Stockholm: Runica et Mediaevalia, 2019). Quotations are taken from this edition.

[2] Cornell Chronicle, 4 March 1998 [accessed 27 April 2020].

[3] Volker Schier, ‘Probing the Mystery of the Use of Saffron in Medieval Nunneries’, in Richard Newhauser and Corine Schleif (eds.), Pleasure and Danger in Perception. The Senses in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (special issue of The Senses and Society, 5 (2010), pp. 57−72.

[4] For example, in England the Great Plague of 1665/66 killed around 100,000 people There was no vaccine, no cure and in crowded cities such as London (a population of c. 384,000 in 1662) no social distancing. The rich self-isolated on their country estates; Charles II and his court moved to Salisbury and then Oxford; the Mayor of London and the city aldermen remained at their posts. The last outbreak of the Plague in this country occurred in Suffolk in 1910.

[5] After the initial outbreak the Black Death returned to Nuremberg in 1405, 1435, 1437, 1482, 1494, 1520 and 1534. In a letter of 1 December 1520 Katerina mentions a family acquaintance whose business is affected: ‘She[the Reverend Mother] is worried that he [a Herr Hess] doesn’t have cash, as he would if he were doing a lot of trading — which is being hindered by the plague’.

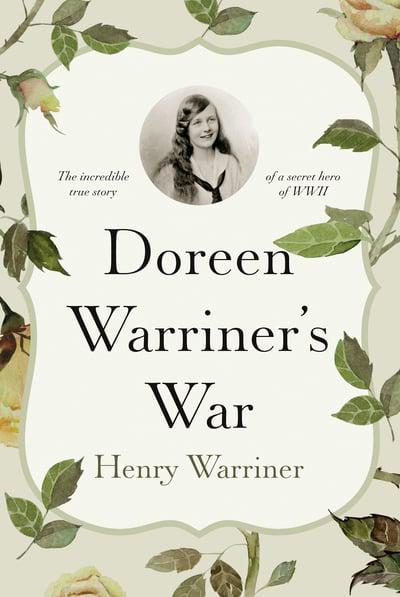

‘What are you reading?’ “Doreen Warriner’s War”, from Jana Buresova

As so many women, including nurses and other ‘front line’ staff currently combatting Covid-19 have suddenly become acknowledged heroes, it is very timely to consider another hitherto unsung hero, Doreen Warriner.

Warriner’s battle, however, was not against the insidious, unseen virus, but an all too visible World War Two enemy in Gestapo uniforms. Working with the British Committee for Refugees in Prague, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), she cared for, and protected as far as possible, the wives and children of mainly political refugees, helping hundreds to escape to safety in Britain during 1938–1939.

It was a dangerous activity which ultimately endangered Warriner herself, forcing her to flee too, in 1939. Overshadowed by the venerable Sir Nicholas Winton in London, who focused on the Kindertransports from Prague to Britain, saving 669 children, Warriner’s selflessness was largely overlooked and then forgotten. Fortunately for present day researchers, nephew Henry Warriner’s book has remedied this, raising her profile and giving her the belated recognition she greatly merits. I, for one, applaud them both.

Dr Jana Buresova, Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies

The Seventh Seal: Putting Epidemic Disease in its Place

Alexander Samson discusses the resilience of people to disease through the ages

As we struggle to find a language adequate to voice our feelings about the COVID-19 pandemic and the radical changes to our everyday lives it has forced upon us, it may be worth remembering that ‘unprecedented’ as it may seem to us, most of our history has been lived in the shadow of epidemic disease.

Even in the 20th century, in addition to the much-referred-to Spanish influenza pandemic that infected as much as a third of the world’s population, there were flu pandemics in 1957 and 1968 each killing around a million people, not to mention HIV in the 1980s.

From the bubonic plague that killed as much as one third of Europe’s population, to waves of sweating sickness, quartain fever, smallpox, plague, typhoid, dysentery, syphilis and many others, pathogens have frequently reminded us of our vulnerability, especially in the period before microscopy.

The Black Death is generally associated in Europe with the wave that hit in 1347, but that was in fact the second pandemic. The first, in the 6th century and lasting two hundred years, may have claimed 25 – 50 million lives. Other epidemics have had huge consequences. While in the Americas smallpox may have decimated populations with no immunity, the mysterious killer cocoliztli, a still unidentified pathogen, perhaps some form of haemorrhagic fever, killed many more in Central Mesoamerica.

Human populations experienced constant waves of epidemic, deadly disease before the 20th century. Their resilience and survival in the face of death on a massive scale is a part of the human story that should give us hope and remind us how short-termist and amnesiac our modern world is in danger of becoming.

There was a time when ‘society’ and ‘experts’ were dirty words. Not any more. Now both seem more necessary than ever. Despite the end of history and the iconoclasm of our time, nature has just reminded us that how far we have come as a species should perhaps not be measured in terms of our successes on average as individuals but how well we are able to come together as societies to confront the greatest challenges facing us, the extent and limits of our collaboration and cooperation.

In Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal (1957 Swedish and Latin) the knight returning from the crusades to a land ravaged by plague plays chess with death to buy time for a young couple and their child, in one final redemptive act. Its apocalyptic title contrasts with the single act of kindness and care at the heart of the film. That we are all interconnected and interdependent has become clearer in the light of this existential challenge that can only be comprehended on a human scale, in our everyday acts of kindness and goodness to one another.

See Emma Smith’s article ‘What Shakespeare Teaches Us about Living with Pandemics’

Dr Alexander Samson, University College London. Vice Dean Education in A&H. Director of the Centre for Early Modern Exchanges and the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters

Considering Oppositional Practices in Arantxa Echevarría’s ‘Carmen y Lola’ (2018)

Rachel Beaney discusses Arantxa Echevarría’s 2018 film Carmen y Lola (Echevarría 2018), which tells the story of two Spanish Roma women who fall in love and are subsequently rejected by their community.

Carmen y Lola presents experiences of sexuality, coming-of-age, prejudice and love. This is the first film to address the taboo topic of prohibited love between two teenage Spanish gypsy women. The film also exposes the gendered stereotypes often adhered to within Spanish Romani gypsy families and was selected to screen in the Directors’ Fortnight section at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. I believe it can also be categorised as an F-rated film:

Una película femenina: No solo la dirección y el guión han sido obra de una mujer, el máximo protagonismo también corresponde a dos chicas como ya indica el título. Pero es que también las hay en muchos otros apartados: productoras, compositora, fotógrafa, vestuario, diseño de arte, maquillaje y peluquería, etcétera. (A female film: Not only have the direction and the script been the work of a woman, the main parts are also two girls, as the title indicates. Women also make up many of the other production elements: female producers, composers, photographers, wardrobe, art designers, makeup artists and hairdressers, etc) (Vicente 2019).

In this piece, I will explore the story of the two protagonists, 17-year-old Carmen (Rosy Rodríguez) and 16-year-old Lola (Zaira Romero), and their navigation of their relationship and the process of coming out the Spanish Romani gypsy community. I consider the tactics of resistance and oppositional practices that can be observed in the plot, through shot analysis of scenes from the film. I will examine the use of graffiti and heterotopic spaces as tactical practices of Carmen and Lola. I will support my analysis with applications of theories including the Queer Child (Bond Stockton 2009).

Director Arantxa Echevarría hails from Bilbao and this film, Carmen y Lola, follows the friendship and blossoming love between the two protagonists of the same names. Carmen, who we see here in glamourous dress, ready for El pedido,the ceremony in which the groom to be asks for her hand in marriage, is about to be married to a man that she quickly discovers has a very uncompromising, gendered expectation of their married life. Carmen meets Lola, another young Romani gypsy, who encourages her to question the way their futures have been mapped out for them and the expectation of their families that they fulfil their traditional gender roles. Together, they begin to navigate and question the patriarchal, conservative and Catholic society in which they find themselves. Perhaps it is the director’s decision, in the style of many neorealist films, French new wave films and many of Spanish director Carlos Saura’s films about youth, to use non-professional actors that gives this film a heightened sense of realism, but this is also supported by the camera work that gives an almost shaky feel with handheld-recording:

Intentamos darle un tono documental para que fuera más realista. Rodamos en un mercadillo de gitanos abierto al público y teníamos un puesto de fruta que alquilamos. Lo más curioso es que muchas veces vinieron clientas a comprarnos sorprendidas por los precios tan baratos que teníamos y algunas de esas escenas se han quedado en la película (We tried to give it a documentary feel so it was more realistic. We shot in a market run by romani gypsies that was open to the public and we rented a fruit stand. What was quite strange was how many times members of the public came to buy fruit and were surprised at how cheap it was and some of those scenes have remained in the film) (Echevarría, cited in Vicente 2019).

Moreover, the film is a reminder that this kind of attitude and prejudice towards non-heteronormative love is still prevalent and young gay people are facing this kind of discrimination the world over. Indeed, as the director also notes, when creating the film, they encountered some resistance from members of the gypsy community, some even shouting at the director that she was evil for depicting a lesbian love story. From the film’s beginning, the cinematography conveys a sense of being watched and constant surveillance through the incorporation of extreme close-up shots and enigmatic point-of-view shots. This kind of concept, of living in fear of what the neighbours will think, of a correct performance of correct values, is translated to the screen somewhat explicitly, as we will see in this next still from the film. In one of the early scenes of the film, a handheld camera shakily frames the community in which Carmen and Lola live. We see this shot of a watch tower and the scene then swiftly transitions to show some children playing in the neighbourhood (see Figure 2). Situating the spectator in this barrio in the suburbs of Madrid, this cinematic framing also sets the tone of surveillance and fear of being watched and judged from the outset. In fact, this shot occurs within the first 3 minutes of the film. Did someone say panopticon?

As Alan D. Schrift has pointed out in his reading, in Discipline and Punish Foucault theorises that

Through various procedures that compare, that rank, that hierarchize, that judge, that select or exclude, that, in all senses of the word, examine, the modern individual is no longer called upon as a subject required to obey the law but is produced instead as an individual who is required to conform to the norm (Schrift 2013, p. 145).

I posit that this can be applied to the Romani gypsy community value system that is imposed on the two young protagonists of Carmen y Lola. This value system is upheld through a system in which the girls will be married off, the structure of the community itself (Romani gypsy communities will have a patriarch, who is usually the head male of the community), and a prejudice towards non-heteronormative, queer relationships. In fact, the director notes that many scenes had to be cut from the film as one of the non-professional actresses from the Romani gypsy community had a serious problem:

Pero un día, la mujer que lo interpretaba me llamó para decirme que su marido había hablado con el patriarca y la habían desterrado y no pudo volver(But one day, the woman that played them called me to tell me that her husband had spoken with the patriarch and they had exiled her and she could not come back) (Vicente 2019).

It is perhaps a simplistic reading but also a pertinent element of symbolism in the film; the power and surveillance that the panopticon brings with it. This sense is then further underscored by subsequent scenes in the film in which we see shots of the windows of the apartment tower blocks that look out onto the communal spaces (see Figure 3). Again, the feeling of being watched by the neighbours is a constant in the film. The Spanish refrain ‘El amor es ciego pero los vecinos no / Love is blind but neighbours aren’t’ is a current that runs through the narrative.

Kathryn Bond Stockton’s queer theory of the child posits that every child is queer:

For no matter how you slice it, the child from the standpoint of “normal” adults is always queer. It is homosexual…or, despite our cultures assuming every child’s straightness, the child can only be “not-yet-straight” since it, too, is not allowed to be sexual (Bond Stockton 2009, pg.7).

Children, per this theory, are queer; there are sexual children, murderous children, gay children, ghostly children. It sets out that children exhibit qualities that we have deemed as ‘adult’ and are ‘shockingly queer’ and consequently do not fit neatly into a binary. We can instead read a child in the films that is loquaciously queer and therefore, recognise its agency in the narrative.

We see the film depict clear ‘sideways movements’, (Bond Stockton 2009, pg. 52) per Stockton’s theory, in the girls’ actions, as they find what, in yet another Foucauldian reading, can be classed as other spaces or heterotopias within the stifling landscape of surveillance. In these spaces, the girls are free to talk, love and dream. This is especially poignant in an intimate scene in an empty swimming pool (see Figure 4). Where the structure of the film initially seems to be a linear coming out and coming-of-age love story, a narrative arc that has already been well trodden in contemporary Spanish cinema by films including Toto forever and Almodóvar’s La mala educación, Echevarría succeeds in providing insights into the asphyxiating control and prejudice experienced by the Spanish Roma protagonists.

What other kind of spaces do they find? In the shot seen in Figure 5, we see the girls in a horizontal position in the suburb’s urban landscape. Here they are enclosed in the space but also surrounded by graffiti. Graffiti, according to Brighentti, is an interstitial practice and, from a political angle, can be viewed as ‘as a message of resistance and liberation’ (Brighenti 2010, p. 316). Hispanist Stephen Luis Vilaseca has explored the paradoxical rhetoric surrounding graffiti laws in cities like Barcelona and Madrid which have criminalized graffiti, whilst galleries including the Reina Sofia in Madrid have co-opted graffiti art for contemporary collections (Vilaseca 2017). In Carmen y Lola, Lola creates graffiti murals as an outlet to express herself. She dreams of studying and moving away from the life that her father desires for her as a housewife. Pointedly, one of the central motifs of Lola’s murals is the image of the bird.

Latin Americanist and scholar of Spanish language visual cultures Rachel Randall has explained that ‘playspaces’ allow youth protagonists briefly to escape social restrictions, and to exercise what could be termed their own ‘imaginative agency.’ She further categorises playspaces in the films she analyses as heterotopias of sorts, in that they create a space that is ‘other’ (Randall 2017). The child protagonists in the Latin American films she analyses ‘appropriate spaces’ in order to create, in Foucauldian terms, counter sites, or ‘places outside of all places.’ Through the journeys of the young lovers in Carmen y Lola which take them to secret enclosed spaces and hidden urban areas, the girls are able to negotiate their own space for play and love, away from the rigid structures of adult rules.

Rachel Beaney, Cardiff and Exeter (AHRC South West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership), Hispanic Studies, Cardiff School of Modern Languages (Supervisors: Ryan Prout and Sally Faulkner)

Works Cited

Almodóvar, Pedro director. “La mala educación”. Warner Sogefilms, 2004. DVD

Bond Stockton, Kathryn. The Queer Child, or Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century, Duke University Press, 2009. Print.

Brighenti, A. M. “At the wall: graffiti writers, urban territoriality, and the public domain.” Space and Culture 13 (3), 2010, pp. 315–332.

Canuto, Roberto. “Toto Forever”. 2010.

Echevarría, Arantxa, director.“Carmen Y Lola”. Super8, 2018. DVD

Randall, R. Children on the Threshold in Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Nature, Gender and Agency. Lexington Books, 2017. Print.

Schrift, A.D. “Discipline and Punish”, A Companion to Foucault, C. Falzon, T. O’Leary and J. Sawicki, 2013, pp. 137-153.

Vicente, E., “El Complicado Rodaje De ‘Carmen Y Lola’, El Romance Entre Dos Chicas Gitanas.” El Periódico. 2019. Available at: https://www.elperiodico.com/es/ocio-y-cultura/20180907/el-complilcado-rodaje-del-drama-lesbico-gitano-carmen-y-lola-7021795 [Accessed 16 April 2020]. 2019.

Vilaseca, Stephen Luis. “Representations of graffiti and the city in the novel El francotiradorpaciente: readings of the emergent urban body in Madrid.” Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, edited by Konstantinos Avramidis, Myrto Tsilimpounidi, Routledge, 2017.