Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Memories of Mobility. Thoughts on an Erasmus+ Training Visit to the IMLR

Britta Jung discusses her recent trip to the IMLR through the Erasmus+ training scheme

People say you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone. Truth is, we did know what we had, we just never thought we would lose it. One of the things I certainly never thought I would lose is the ability to move with relative ease within my community, city and country, and indeed beyond. To visit family and friends. To engage and discuss with my students and colleagues face to face. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to hold the world in a stranglehold and – as the CCTV images of the world’s usually boisterous cities and metropoles all too well illustrate – brings it to a standstill I, like so many others, scramble to adapt to the circumstances professionally as well as personally. I also happen to be thinking back to those precious few days at the end of January when an Erasmus+ Staff Training brought me to the Institute of Modern Language Research. It was meant to kick off a rather full travel and research itinerary for 2020. While I might not have known at the time that my other plans would fall through and I would get a crash course in digital literacy, I did know how fortunate I was to be able to travel to London thanks to the support of the UCD Humanities Institute and the IMLR, the generous Erasmus+ grant from the European Commission and the relative ease with which I can travel throughout the world on my German passport – the latter being particularly relevant given the short notice on which the trip was planned. But I will come back to that in a minute.

Generally speaking, my work thrives on close, personal interaction with my students and peers, and many projects and articles have been the result of this (I am clearly not one to live up to the imagery of the solitary academic working away in their quiet attic room). It has also very much shaped the way I teach and mentor students. Personal interaction serves as both an inspiration and a sounding board, it helps me to change gear and look at things from a different perspective, and it grants me access to specialist knowledge and cultural layers of meaning I might have previously been unaware of, particularly as the scope of my research and academic work continues to extend beyond disciplinary and national borders. Indeed, my time at the IMLR afforded me – among other things – the opportunity to reflect on the, at times subtle, at other times less subtle, differences between the Irish, British and German academic culture and student supervision.

But how did this particular Erasmus+ training come about? What did it mean to achieve? And why was it so hastened?

The UCD Humanities Institute and the IMLR’s Erasmus+ programme was established over a year ago to further strengthen our longstanding partnership; two conference have been run under its auspices and a lively exchange of ideas has taken place since. In this context, Dr Godela Weiss-Sussex (Acting Director of the IMLR) and I have been planning to undertake a teaching-based exchange for some time now. However, as I found myself tied up in an applied research project for the Higher Education Authority and teaching commitments at UCD, the exchange kept being pushed back. It was only the results of last December’s general election and the increasing uncertainty around the UK’s future involvement in the Erasmus+ programme and its general relationship with the EU that set the wheels in motion. Given the lack of definite answers on what the UK’s departure of the European Union would mean in terms of Erasmus+ mobilities from February onwards, time was suddenly of the essence. In a joint effort, that was further complicated by the imminent Christmas break, we came up with an exciting and meaningful new plan for the exchange, shifting its focus from teaching to training and career development. The flurry of emails and signatures lasted well into the new year and I finally was able to book my flight the week before I left for London.

As I boarded the plane, I hoped that I would not be the last member of either institution to embark on such an Erasmus+ training, that the UK would continue to participate in the EU’s flagship programme after the transition period ends and allow students and staff to benefit from the existing infrastructure and mutual exchange. It would certainly not be an exaggeration to say that Erasmus programme has played a huge part in my life. I would probably not even be in Dublin right now, working on my second monograph and said applied research project, without my first Erasmus student exchange to the Netherlands back in the early 2000s. After all, it was during that sojourn that I was encouraged to return after my graduation in Germany and pursue a PhD. It has been more than a decade and a half since I last ‘went on Erasmus’ and, by all accounts, my training at the IMLR proved once again an enriching and inspiring experience. My three days at the IMLR afforded me not only the opportunity to consolidate and further establish professional links with individual members of the Institute but also to share my own expertise in Migration Studies and gain new knowledge in a wide range of theories and methodologies, including Postcolonial Studies and Gender Studies as well as the Digital Humanities and Empirical Research.

A personal highlight, however, was the shadowing of Dr Godela Weiss-Sussex during her meetings with two PhD candidates, one of whom had just started their PhD journey while the other was passing the final milestones before coming to an end. As I still have very little personal experience with supervising PhD candidates due to the nature of my Fellowships, the meetings allowed me to step back from my own experiences as a supervisee and to observe the needs and interactions from a more neutral point of view. Together Dr Weiss-Sussex and I reflected on the nature of supervision, its challenges and changes over time as well as – as previously mentioned – the cultural differences between Ireland, the United Kingdom and Germany. For instance, we discussed the effects of the internationalisation of higher education and implementation of tighter procedures in many institutions as well as the notion of the German terms ‘Doktormutter’ or ‘Doktorvater’ which imply a highly personal supervisor/supervisee-relationship, whereas this relationship is in fact traditionally characterised by a decidedly less hands-on supervision than in the UK and Ireland. These first-hand experiences and reflections provided a starting point for a series of career development workshops on research supervision that I will be following at UCD once this pandemic is over and we return to relative normalcy. I also enjoyed reading and providing my own feedback on the chapters under discussion in the supervision meetings and would hereby like to – once again – extend heartfelt thanks to both PhD candidates for sharing this part of their work with me.

Another highlight was my session with Dr Naomi Wells who took it onto herself to slowly walk me through the rather expansive field of the Digital Humanities. It was a fascinating session that not only introduced me to the general field and its concepts (I have to admit that my mind was blown on one occasion or two) but also to Dr Wells’ own research which focuses on languages and migrant communities and therefore echoes to some extent my own work on migration literature and transcultural encounters. The discussion was lively, and I am sure there are future avenues of collaboration to be explored. The academic exchange continued during a special session of the IMLR’s Brown Bag Seminar Series, in which various Institute PhD students, Fellows, staff and I presented our current projects and discussed their transnational/transcultural dimension.

However, as no research or work trip can be reduced to – well – work, this one too had much more to offer beyond the seminar rooms and IMLR offices. While I have been to London countless times, there’s always more to see. I explored the picturesque streets of Bloomsbury and then moved on to other areas of London. I took my obligatory picture of a crowded Piccadilly Circus and Regent Street (which I always take) and strolled by Buckingham Palace and Westminster. I also had the chance to finally take up my late sister-in-law’s recommendation to watch the Book of Mormon in the West End and I happily indulged in the many sensory offerings of London’s multi-ethnic food scene.

So, yes, as I am sitting here in my Dublin flat in the middle of a pandemic that has halted any notion of mobility beyond a radius of 2km, I fondly remember my short visit to the IMLR and what I have learned. I think more systematically about whether and how I can apply certain aspects from Postcolonial Studies and Gender Studies to my own research. I think about what I have discussed with Naomi with regard to the Digital Humanities and how to further explore the area in relation to my own work. I think about my conversations with Godela on student supervision as I try to mentor my undergraduate students through these challenging times. Oh, and I do all this listening to the Book of Mormon soundtrack (I am sorry to say pretty much on loop), while craving some fiercely good chicken tikka masala. I truly never thought I would lose the ability to just pop over to London and the IMLR, which are just an hour away by plane. So, let’s just hope we will soon get back what we have lost due to the current pandemic and that the future will indeed hold many more Erasmus+ exchanges despite the UK’s departure from the European Union.

Dr Britta Jung, University College Dublin, UCD Humanities Institute

‘What are you reading?’ Nautical novels | Novelas nauticas, from Catherine Davies

I’ve just finished reading Pío Baroja’s 1911 novel, Las inquietudes de Shanti Andia, which I read twice because the novel only makes sense if you go back to the beginning. I used an old 1970 edition, with an introduction by the famous Julio Caro Baroja, and a plethora of useless notes. I first read Shanti Andía when I was a student forty years ago and I thought it at the time unremarkable. I’ve now come back to it, unfairly perhaps, after a first encounter with Baroja’s contemporary, Joseph Conrad. Why, I asked myself, are there so many fine British novels about ships and the sea and none in Spanish? Then I remembered Baroja’s tale of Shanti, the Basque seaman. My colleague, Rory O’Bryen, came up with a few more twentieth-century examples: Alvaro Mutis’s ‘Maqroll’ novels (Colombia), published in the 1980s and 1990s; Alejo Carpentier’s El siglo de las luces (Cuba), though it’s more about revolution; possibly Cristina Peri Rossi’s La nave de los locos (Uruguay/Spain) (though the sea is largely metaphorical) and Soledad Acosta de Samper’s Los piratas en Cartagena written in 1885 (Colombia). Then there is the Spanish classic Trafalgar by Benito Pérez Galdós (1873), and Arturo Pérez Reverte’s far superior Cabo Trafalgar published in 2005, though they’re about a battle. The question remains: Conrad, Stevenson, Marryat, O’Brian, and Melville in the USA – but why are there so few nautical novels in Spanish? And hardly any in the nineteenth century? Could it be that the novel is a nineteenth-century phenomenon and by then Spain had lost interest in the oceans, while Spanish America is hardly famous for its home-grown sea captains?

Caro Baroja, in his introduction to Shanti Andía, states that Baroja was influenced by Captain Marryat, the Royal Navy Officer who published a dozen sea novels in the 1830s. But surely Baroja must have read Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1882) and possibly Conrad’s Lord Jim (1900) or Typhoon (1902), perhaps in French editions? Even in the sea stories the difference between Baroja and Conrad is immense. In his heart of hearts, Shanti Andía never leaves the shore, his sea-faring is glossed over in a sentence or two; his centre of gravity is his home, his mother and his wife. It is his uncle, Juan de Aguirre, who most resembles Conrad’s ‘masters and commanders’, whose tumultuous life takes him from the Philippines to Cadiz, Cape Verde to Plymouth and Wexford. And like Conrad, Shanti Andía laments the demise of the age of sail with wistful nostalgia. Unlike Shanti, Conrad’s seaman never leaves the sea; his place of attachment is his ship. He has no time for shore-life or for women. His world is a self-sufficient gaggle of men, thrown together from all corners of the globe, and their unexpected bravery and their tragic self-destruction when faced with the immense and inscrutable forces of nature. Their woman is their ship; they care for her, cook, clean, and steer her to safety with disciplined skill. The most unassuming of the Conrad crew are the most valiant, but it’s all in a day’s work. Unlike Baroja, Conrad was an active seaman and for this reason knows in minute detail the construction and working of ships, the daily routine and boredom and the hanging on for dear life. Baroja the Basque and Conrad the British Pole, contemporaries who wrote novels about the sea – one with an eye on his grandmother’s living room the other from the eye of the storm.

Catherine Davies, Professor of Hispanic and Latin American Studies, IMLR

“’My cell is so narrow,’ you may say, but oh, how wide is the sky!”

Dr Godelinde Perk writes about self-isolating women in late-medieval Europe

The pandemic of COVID-19 is often called “unprecedented” – and for many people cooped up in their homes in different countries, the experience is both unparalleled and challenging. But in late-medieval Europe, individuals self-isolated professionally. Some people – women particularly – permanently withdrew from society to live walled in, alone in a room attached to a church.

(Rothschild Canticles), Yale Library

Guides for, and texts written by, these female “anchorites” – as the women were known – from Britain and continental Europe give us descriptions of their way of living and recount their reflections. So what can these medieval women teach us about how to cope with self-isolation?

These anchorites chose to be confined in these cramped cells for many reasons. According to medieval religious culture, a life of prayer on behalf of others vitally supported society. Isolation empowered women to express their love for Christ, and minister to their fellow believers through their prayers and counsel. Anchorites were even presented as possessing “super powers” of interceding for the deceased in purgatory.

Furthermore, in the late Middle Ages, devotion among laypeople – people who are not clergy – flourished. Life as an anchorite offered laywomen an option to express this piety, but offered more freedom for individual contemplation (and solitude) than a nun’s life.

Warnings in guides for anchorites also hint at less spiritual motives. Life as a recluse, paradoxically, situated anchorites at the heart of their communities and could transform them into religious celebrities. Their cells often faced busy roads in bustling cities and doubled as a bank, teacher’s cubicle, and storehouse of local gossip.

Don’t expect comfort

The 13th-century, medieval English guide for female anchorites, Ancrene Wisse, warns recluses not to look for comfort. Instead, the anchorite should remind herself that she was enclosed not just for her own benefit, but for the sake of others too.

She is told: “gederið in ower heorte alle seke and sarie” [“gather into your heart all those who are ill or wretched”]. The Wisse also instructs the anchorite: “habbeð reowðe” [“feel compassion”]. By self-isolating, the anchorite “halden hire up” [“holds [all fellow believers] up”] with her prayers. Now, nurses and doctors are urgently calling for a similar commitment from the public, when begging “Stay home for us.”

The Wisse’s advice has a flavour that feels equally relevant today. Self-isolation may be easier to bear if instead of seeing it as a stretch of boring but comfy nights in, you recognise it as an unpleasant, stressful experience – but also visualise all the people whose health you are protecting by staying home.

Acknowledging vulnerability

The earliest-known English woman writer, Julian of Norwich (c.1343–c.1416) – an anchorite – likewise encouraged readers to acknowledge their own vulnerability, but suggested perceiving it as a strength. She assured readers in her late 14th-century or early 15th-century text, A Revelation of Love, that suffering and difficulties will not defeat them:

He saide not ‘Thou shalt be tempested, thou shalt not be traveyled, thou shall not be dissed’ but he said ‘Thou shalt not be overcome’.

[Christ] did not say, ‘You shall not be perturbed, you shall not be troubled, you shall not be distressed,’ but he said, ‘You shall not be overcome.’

Julian promises that readers will experience emotional turmoil during any crisis but will ultimately conquer it. This promise parallels modern survival psychology. When adapting to life during a crisis, acknowledging the challenging circumstances as forming one’s real life now is essential. Yet one should simultaneously remember that one is doing one’s utmost to return to a better, pre-crisis style of living. Only by acknowledging our vulnerability – both physical and mental – and consequently taking action to protect and care for others and ourselves, will we make it through.

Guarding the senses

According to manuals for anchorites, they should guard their metaphorical windows (their five senses) and actual cell windows, to prevent falling into temptation and being distracted from their prayers and meditation. The Wisse declares: “Nurð ne kimeð in heorte bute of sum þing þet me haueð oðer isehen oðer iherd, ismaht oðer ismeallet, ant utewið ifelet.” [“Disturbance only enters the heart through something that has been either seen or heard, tasted or smelt, or felt externally.”]

Photo by E de Groot & S Pieters, University of Utrecht

The external world can upset one’s interior world. Dutch anchorite Sister Bertken (1427-1514) recounts this confusion in a poem:

Dye werelt hielt my in haer ghewalt

Mit haren stricken menichfalt.

Mijn macht had si benomen.

[The world held me in its power

with its manifold snares

it deprived me of my strength.]

Yet this nervousness about the effect of sensory input can also be understood as a medieval analogue to a warning against fake news or anxious over-consumption of news. Several guides recommend having a female friend scrupulously guarding the anchorite’s window, refusing to allow access to visitors who spread gossip and lies. Social media today can be a little like such visitors.

Keep busy, keep sane

Anchorites and writers of manuals for anchorites also reflected upon how to keep sane. Keeping occupied prevents one from climbing the walls. British Cistercian monk, Abbot Aelred of Rievaulx (1110-1167), tells his sister, an anchorite, in ‘A Rule of Life for a Recluse’ that: “Idleness … breeds distaste for quiet and disgust for the cell.”

Routines are key. Anchorites recited sequences of prayers, psalms and other Bible readings at fixed points of the day. According to modern survival psychology, dividing a problem or stretch of time into manageable steps is crucial when faced with a crisis. Equally important is performing each step one by one, never looking further ahead than the next step.

Mentally absorbing hobbies, such as crafts, gardening or reading, are another time-honoured strategy for dealing with self-isolation. After recommending sewing clothes for the poor and church vestments, the Wisse assures anchorites that keeping occupied will shield their minds against temptation:

For hwil he sið hire bisi, he þencheð þus: ‘For nawt Ich schulde nu cume neh hire; ne mei ha nawt iȝemen to lustni mi lare’.

For while [the devil] sees her busy, he thinks like this: ‘It would be useless to approach her now; she can’t concentrate on listening to my advice.’

These suggestions are easily translatable to today. After all, according to survival psychology, performing manageable, directed actions with a purpose is crucial in crises. Incidentally, the Wisse also recommends keeping a cat.

On the one hand, self-isolation can feel limiting – Julian of Norwich also felt that: “This place is prison,” she said, referring either to earthly life or her cell. But the cell’s cramped space also granted medieval women a paradoxical, spiritual freedom. In his letter to the anchorite Eve of Wilton, the 11th-century monk Goscelin of St Bertin exclaims: “’My cell is so narrow,’ you may say, but oh, how wide is the sky!”

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Godelinde Gertrude Perk, Postdoctoral researcher in Medieval Literature, University of Oxford.

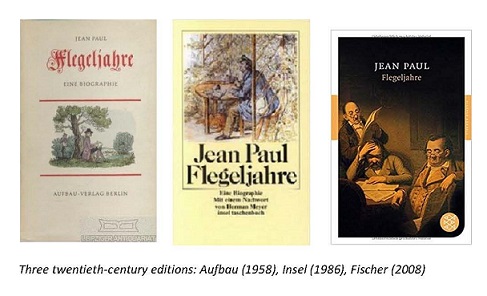

Staying at Home — with Jean Paul. ‘Flegeljahre’ and Frustrated Idylls

Dr Seán Williams discusses Jean Paul Richter’s ‘Flegeljahre’ and its place in his thoughts on luxury, and its relevance to today

Life in lockdown is, by definition, domestic. Of course it’s frustrating, but because I’m normally not the organised sort in sourcing home supplies, I’m enjoying the novel challenge of a weekly shop. (Though I deplore stockpiling, I fear I’ve contributed to the problem with my own false calculations about how much I actually eat in a week. Perhaps I’ve just lost my appetite, with Armageddon going on outside.) In any case, we can seek relief from the coronavirus chaos in reading. And being a lover of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, I’m in luck: authors of my preferred period are all online; their works are free to download. So over the past fortnight, I’ve spent some of my time at home with Jean Paul Richter.

Jean Paul and I have a history. I spent my doctoral years reading him with an eye to literary and intellectual history around 1800, and paratexts in particular. His prefaces about prefaces were the subject of my first book. Now, I’m just as interested in, say, the ‘Inn of the Inn’ — or ‘Wirtshaus zum Wirtshaus’ — from his unfinished novel Flegeljahre (1804-05). In other words, as my research has moved more into cultural history, and specifically subjects such as emergent consumer capitalism and the new social status of professions like the hairdresser, my starting point is a familiar one: Jean Paul’s fiction. He incessantly alludes to contemporary everyday, and especially domestic life, doing so with self-reflexive turns typical of his time (hence the ‘Inn of the Inn’). Jean Paul’s writing is as encyclopaedic as it is eccentric. He opens Flegeljahre by speaking to literary, intellectual, cultural, and also political history that sits on the threshold from the eighteenth into the nineteenth centuries. To quote a mid-nineteenth century English translation:

‘I shall touch upon vaccination, the book and wool trade, the monthly periodicals, Shelling’s double system of magnetism and metaphors, the new territorial boundary marks, with the illegal duties; also, field mice and caterpillars, and Buonaparte. These last I shall touch only cursorily, and as becomes a poet.’

[‘Ich berühre darin die Vakzine – den Buch- und Wollenhandel – die Monatsschriftsteller – Schellings magnetische Metapher oder Doppelsystem – die neuen Territorialpfähle – die Schwänzelpfennige – die Feldmäuse samt den Fichtenraupen – und Bonaparten, das berühr’ ich, freilich flüchtig als Poet.‘]

Plenty to occupy us, then. Yet what makes Flegeljahre so fascinating is that there is the sense of society around 1800 encountering an uneasy transition. The optimism of the Enlightenment has faded; faith in an aesthetic education — or the German concept of Bildung, an intellectual, spiritual development of the self — as the path towards collective progress is obviously misplaced. But Jean Paul does not abandon the cultural ideal of Bildung altogether. The protagonist twins from the Flegeljahre, Walt and Vult, are writers themselves, though neither of them is a model character. Vult is a picaresque, almost baroque travelling flautist who flits in and out of the fiction at whim. Walt is committed to his home place, and in that sense more grounded than his brother. But he’s far too much of a dreamer. He’s inspired by Wutz, the literary, rural, impoverished schoolmaster of an early idyll by Jean Paul: a figure who buys into the world of the mind despite, for someone of his situation, the unaffordability of books, such that that he writes the stories whose titles are listed in trade catalogues himself, just as he imagines them. If Wutz of 1793 can find contentment despite the constraints of contemporary German life, however, Walt’s escapism a decade later is repeatedly reeled back to reality with a thump (though he seems to withstand each knock with a naive, if charming smile). Walt’s idylls are all the more frustrated, therefore. Not least for this reason, Jean Paul’s Flegeljahre might appear appropriate reading at present — a very different age of frustrated domestic idylls.

The standard problem for middle class men of Jean Paul’s day, epitomised in Goethe’s character of Werther in the 1770s already, was that the late eighteenth century had unleashed the intellectual and artistic potential of German youth, only for it to be made impotent by philistine bureaucrats and capitalists, and by the old aristocratic order that in German territories was still in power into the nineteenth century. At least, that is how many authors perceived it, as they resisted a conservative straightjacket, but wanted to make a success of everyday life all the same. In Jean Paul’s works, there’s also a social consciousness at stake — not so much for the bonded peasants, to whom Voss and the rural Enlightenment gave a voice — but for the local squeezed middle, as it were. Jean Paul’s characters are usually born free, but just about manage to get by, not least materially. So it’s no surprise that luxury is used to describe social differences, by Jean Paul like his many contemporaries.

In Flegeljahre, it is the books in exquisite bindings, gilded ceilings, and other ostentatious objects that make a stranger of the local count to Walt. And when Walt is mistaken for someone else in being assigned guest lodgings, he is astounded by the ‘splendour of a splendorous (state) room’ (‘Prunk des Prunkzimmers’); the accommodation’s opulence includes hung paper instead of plastered wallpaper (‘die Papiertapeten statt des ihm gewöhnlichern Tapetenpapiers’), furniture such as commodes and many mirrors, and so on. Walt is used to village life; on arriving in town, he’s taken aback by the scene of urban life: golden carriages passing by, people wearing red cloaks, and hairdressers — the newfangled friseurs — apparently working every day of the week. This picture of society is set against the backdrop of emergent consumer capitalism, even in the German principalities. Around 1800 was a period of proto-industrialisation. And so at the end of the Flegeljahre, there is a hint of cultural nostalgia — for a supposedly easier age. One of the symbols of late eighteenth-century consumption was linen. As the narrator Jean Paul quips wistfully, were his time not the reign of Charles VII of France, in the fifteenth century, for then ‘in the whole land no one possessed a change of linen, except the King’s wife’ (‘es wäre jetzt wie unter Karl dem VII. von Frankreich, wo im ganzen Lande niemand zwei Hemden besaß als seine Gemahlin’).

Jean Paul’s nostalgia misread the past, but it was alive to the present. Indeed, throughout Europe at the turn of the nineteenth century, luxury was no light-hearted topic. Thinkers began to suggest that, far from leading to general prosperity, luxury was a pan-European problem that in fact could bring about poverty. The economically liberal doctrines of Adam Smith, heralded in the late eighteenth century, came in for special criticism at the beginning of the nineteenth. For Charles Hall, luxury was at fault because it robbed workers of valuable labour time, which they could otherwise and more usefully spend on their own subsistence. For Jean Paul, writing in an essay of 1808, luxury caused poverty because it wasted money. For him, the extreme differences between the material lives of the rich and the poor were a problem. After the French Revolution, then, not only poverty but equality was at issue — albeit not phrased so starkly in German territories. As part of the argument, Jean Paul opposed better and worse types of luxury with each other, though the good sort was in some senses still the lesser of two evils. In his 1808 essay, he contrasts a ‘furniture luxury’ (‘Möbeln-Luxus’) or even ‘class-conscious luxury’ (‘Standes-Luxus’) on the one hand, with a ‘people’s luxury’ (‘Volksluxus’) or ‘luxury of pleasure’ (‘Genussluxus’) on the other. In other words, while the higher social ranks are criticised as having an insatiable appetite for grandeur that craves foreign appreciation, the German ‘nation’ or people as a whole could be excused a self-regulating pleasure in luxuries that are akin to Sunday rest after a working week. Permissible luxury is metaphorically the light of the sun rather than its reflections in houses.

To return to my own readerly position, Jean Paul’s Flegeljahre and its place in his thought and literature on luxury appears relevant in a couple of ways. First, and more personally, I have spoken and written about luxury in the past year, and I teach a module on ‘luxury and liberty’. My own reflections on this topic began by reading Jean Paul. I am currently planning a colloquium on luxury around 1800 for spring 2021, which in the current pandemic and given talk of economic recession might appear decadent. But luxury is often a litmus test for the direction in which society will go. For example, when Swiss grand hotels suffered after the First World War, attempts to create hotspots of ‘affordable’ accommodation, and thereby populate deserted spas, came to nothing. Capitalism was rebuilt. For now, LVMH may have re-purposed their factories to produce hand sanitiser, and InterContinental hotels in London are housing the homeless. How these upmarket businesses will fare after the crisis will be indicative of socio-political undercurrents. If these few examples constitute a tangent about the future — how Jean Paulish of me to digress — let us think again about the homely here and now. To that end, Jean Paul’s typology of acceptable versus unacceptable luxury places a high social value on the artisans. The small pleasures on our Sundays, our home days, are brought to us by their crafts. Currently, 5* hotel rooms stand empty, and booking a break to one of them for whenever normality might return seems futile. So it occurs to me that when stuck at home, and thinking about my weekly shop, I might as well heed Jean Paul’s advice, as well as read him. I’ll turn not only to books for the next few weeks for solace, but also to the little, apparently more wholesome luxuries of local (online) artisans.

Seán Williams is Senior Lecturer in German and European Cultural History at the University of Sheffield

“Bueno parcero, aquí nos separamos”: Colombian Sociolect ‘Parlache’ in Literature and Translation

Aled Rees talks about his time spent at the IMLR as an OWRI Visiting Fellow, December 2019 to February 2020.

During the mid-1980s, a unique heterogeneous urban language emerged from the shantytowns of the Colombian city of Medellín called parlache. Spoken primarily, although not exclusively, by the youngsters immersed in the criminal underworld brought about, in large part, by Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cartel, parlache is a linguistic deviation of standard Spanish involving a revitalisation of antiquated Spanish; an imaginative “re-semanticisation” of existing Spanish lexicon; and in many instances, embraces a visual and metaphorical aesthetic which makes it largely inaccessible to members of the general population.

My fascination with parlache arose during my time working as a postdoctoral researcher on the Cross Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community (Translingual Strand) project based at Swansea University where I, alongside Professor Julian Preece, examined the various forms in which novelists incorporate and utilise multilingualism and translingualism in their writing. As a Visiting Fellow at the IMLR, I sought to complement and develop my previous research by investigating the representation of this sociolect in contemporary Colombian literature and the corresponding English language translations.

My first project at the IMLR was to expand on the existing scholarly discourse centred on parlache by extending the socio-linguistic perspective that this sociolect acts as a form of social protest against a dominant cultural order from which its speakers find themselves excluded. Using a theoretical framework rooted in Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s theories of “minor literature” (1983), I analysed Jorge Franco Ramos’ Rosario Tijeras (1999) and Fernando Vallejo’s La virgen de los sicarios (1994) to address the ways in which these novelists have represented and utilised this ‘minor language’ in their fiction to not only emphasise the communitarian sense of belonging that this sociolect generates amongst its speakers (despite the frequent cases of gang warfare and the existence of diverging factions!), but also as a means of subverting traditional hegemonic practices. In order to carry out this research, I made extensive use of the Latin American Studies collection at Senate House Library in relation to the investigation of the historical role in which language has played within the Colombian nation, particularly with regards to its association with power and the ways in which it has acted as a means of exclusion.

Moreover, owing to the linguistically hybrid nature of parlache and its embracement of neologisms, archaisms, stylistic innovations and “re-semanticisations” or “revitalisations” of already existing Spanish lexicon, I was curious to discover the ways in which the translators of both Vallejo’s and Franco’s narratives have rendered such terminology in English. This would form the second part of my project. Drawing on Lawrence Venuti’s domestication vs foreignization dichotomy, I explored the translation strategies employed in the rendering of this sociolect to discover the extent to which this culturally and geographically embedded language was compromised in the transfer between source and target text.

In order to complement my research into this area, I organised for the event entitled ‘Latin America in Translation: Traversing Cultural and Linguistic Frontiers’ to take place on 25 March 2020. However, due to the unprecedented situation caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the event had to be postponed and will be rescheduled for a date later in the year. The event was to take the form of a roundtable conversation involving two widely acclaimed translators who are active in the field of literary translation – Nick Caistor and Cherilyn Elston – and had the aim of discussing the importance and complexities of translating diverse Latin American cultural and linguistic realities to an Anglophone readership. Particular attention was to be paid to both the idea of cultural interchange between divergent communities as well as the issues which arise in relation to the rendering of transcribed orality, dialect, colloquialisms, and geographically embedded phrases in the region’s fiction and nonfiction. As a mode of visibly demonstrating some of these issues, the translators had prepared brief presentations of excerpts of their own translations in order to offer an insight and explanation into their own method and decisions while translating. I look forward to rescheduling this event for some time in the autumn.

As the School of Advanced Study is home to several research institutes, I had the opportunity to attend events, presentations and seminars which were taking place. These included Dr. Nadia Mosquera’s (ILAS) talk on the Afro-Venezuelan population’s use of folklore as a means of political mobilisation and the IMLR’s seminar focused on discussing the contemporary culture of Brazilian cinematography and the difficulties it is currently facing. Additionally, I participated in the IMLR’s Brown Bag seminars in which members of the Institute – researchers, fellows and doctoral candidates – gathered to talk about their work and engage in encouraging and supportive discussions regarding possible current and future avenues of study.

My experience as a Visiting Fellow at the IMLR has been extremely positive not only in terms of the research I have been able to carry out using the extensive Hispanic, Latin American and theoretical resources available at Senate House Library, but also with regard to the opportunities to attend and participate in activities and events organised by the various institutes as well as the ability to engage with fellow researchers and academics based at the school. I will remember fondly my time at the IMLR and would recommend undertaking a fellowship there to everyone.

Dr Aled Rees, OWRI Visiting Fellow at the IMLR