Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

The Pathological Body: European Literary and Cultural Perspectives

Dr Kit Yee Wong reports on the symposium that she organised at the IMLR in September 2019, generously supported by the Cassal Endowment Fund and the Society for French Studies

What is sickness and the ‘pathological’ body? How can literature and film help us find out? This international cross-disciplinary symposium in September 2019 at the IMLR brought together ten researchers (from the UK, Turkey, Germany and Australia) working on the intersection between the Modern Languages, literature, and ideas of sickness to discuss these questions. The papers covered the mid-nineteenth century to the present, tracing the birth of modern medicine. We saw that the growing professionalisation of medicine was entwined with politics and cultural biases across the five nations that were discussed: Spain, France, Turkey, Italy and Germany. The three panels looked at the nation(s), subjectivity and therapy/cure.

The language of pathology infiltrated literature across Europe. Writers in nations such as France, Spain and Turkey described key moments in their countries using this new lexicon of sickness. The metaphysical and the clinical became transposed in the national arena, and this was reflected by writers. For authors such as George Sand (1804–76) and Pío Baroja (1872–1956), metaphors of illness and disease helped them write about France and Spain. Ideas around sickness circulated throughout Europe: the nineteenth-century cultural phenomenon of degeneration was widespread. Pathology described the state of the nation, and not economics; cultural anxiety demanded healthy bodies for a healthy nation. Nothing but the collective will could save the nation. Simultaneously, the figure of the doctor would be someone who could heal both people and society.

Medicine was supposed to reveal the ‘truth’. The word vérité (truth) appears frequently in Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s 1924 biography of the Hungarian doctor Philippe Ignace Semmelweis (1818–65). Yet, we need to turn to literature and film to uncover the truth behind sickness. Under the patriarchal framework of Francoist Spain (1939–75), male identity was forged through a mythical embodiment of man using a military model, creating the hypermasculine national ideal of the ‘yo ideal’. Two Spanish films (Calle Mayor, 1956; Los golfos, 1959) worked to undermine this hegemonic masculinity by depicting male anxiety. From psychological alienation to alienation of the body, Marie Darrieussecq’s 2017 novel Notre vie dans les forêts focuses on our desire for human perfection through transhumanism. The text itself reveals the profound difference between individual and institutional (medical) meanings of the body. Illness becomes a sign of humanity in the novel, with the narrative’s discontinued form.

The entanglement of text and medical discourse continued in the discussion of Alfred Döblin’s (1878–1957) Expressionist stories. In his ‘psychiatric aesthetics’ on the ideology of the will over the body, Döblin critiques the normalising rules of society. As with Darrieussecq, the narrative sense is subverted by the bodies that underwrite them. But literature also provides restoration: two papers offered pathography and the act of translation as instruments of healing. Anne Cuneo (1936–2015) and Lydia Flem (1952–) wrote accounts of their breast cancer to regain their identity. The stories were a quest for reclaiming the self in voicing the corps médical (medical body). This act of healing was important for another paper, where illness is a ‘foreign tongue and land’ and translation becomes therapy: it allows the ability to express illness in one’s own words, and to translate the doctor’s jargon into comprehensible language. Again, we encounter the alienating effect of medical terminology in contrast to the everyday language of the patient.

The keynote talk re-emphasised the link between political and biological language from the nineteenth century to the present day, a technique used by politicians against migrants. Echoing previous papers, the body was understood to be at once national, social and individual — if sickness affects one, it affects them all. Many linguistic commonalities between literature and medicine were highlighted: ‘poison’ was a common nineteenth-century French euphemism for syphilis, beginning with Balzac. Focusing on cells, viruses, bacteria and skin as being part of the political-biological concepts underpinning the notion of borders as defenders of health, keynote speaker Steven Wilson (Queen’s University Belfast) argued for novels on ‘insides’ in disease literature.

The symposium was valuable in seeing how literature and film convey the body as the locus of society’s anxieties, and the related movement of ideas through Europe. In particular, the cross-disciplinary aspect was revelatory. Seven of the talks are available as video from the IMLR website.

Dr Kit Yee Wong (Birkbeck, University of London)

Conference twitter account: @pathbodylit

Reflections from a Visiting Scholar at the IMLR

Eduardo Ho-Fernández talks about his time spent at the IMLR as a Visiting Scholar in the summer of 2019

The purpose of my Visiting Scholarship in the Institute of Modern Languages Research (IMLR) at the School of Advanced Study (SAS) of the University of London was to expand on two Renaissance research projects dealing with topics where linguistic and literary analysis intersected. The first project meant to explore the relationship between Erasmus and Juan de Valdés in relation to the scathing critique that Antonio de Nebrija received from Valdés in his Diálogo de la lengua (c. 1535). The second project meant to explore the linguistic features observed in the poems of bilingual Portuguese authors (e.g., Don Manuel de Portugal, Diogo Bernardes) who wrote in Spanish during the Iberian Union (1580-1640). In addition to these two projects. I can say that my experience at the School of Advanced Study far exceeded my highest expectations and I would strongly encourage pre-doctoral stage scholars to look into the many advantages that a Visiting Scholarship could bring to their overall academic portfolio.

Right after my introductory meeting at the Institute, where I outlined my research agenda to IMLR Director, Professor Catherine Davies, I received from her a list of members of the academic staff within the University of London that Professor Davies thought could potentially benefit me in addressing my research questions. Because it was summertime and my time was limited, I spent the rest of that first week contacting and setting-up appointments with the referred faculty members. In the meantime, I visited the Rare Manuscripts Division within Senate House and found/reviewed an early translation of Erasmus’ Colloquies. Professor Davies’ suggestions were outstanding, but getting in touch with the staff at the Warburg Institute to inquire about documents I had been seeking for months proved to be a point of great inflection in how I approached one of my projects. Once in touch, the current librarian at the Warburg suggested that I tried reaching out to the recently-retired head librarian at the Warburg Institute and now Professor Emerita, Jill Kraye. My interactions with Professor Kraye and what I was able to accomplish at the Warburg were significant and merit additional discussion.

One of the main goals for my Visiting Scholarship was to find the Latin-to-English translation of the letters documenting the epistolary relationship between Erasmus and Juan de Valdés. Prior to my Visiting Scholarship, I had not been able to find any bibliographical reference or the catalog number for these letters; but with the assistance of Professor Kraye at the Warburg, I finally encountered the elusive translated letters from the hundreds of letters that Erasmus wrote in his lifetime – and that was a very special and long-awaited moment for me. I also reviewed additional writings by Erasmus and of important modern biographers of Renaissance authors. From the former, of note was the English translation of Erasmus’ Ciceronianus, where Nebrija actually receives direct praise by Erasmus for his Latin style. This particular finding geared my research in a completely different direction, and I am currently evaluating its impact on my hypotheses. I cannot imagine connecting as many dots as I did with respect to the Nebrija vs Valdés controversy, and the different perspective I gained on Erasmus, without the specialized resources made available to me at the Warburg through this Visiting Scholar programme and Professor Kraye’s challenges to my thinking.

I was also fortunate enough to meet with Professor Emeritus Trevor Dadson, Professor Emeritus Christopher Pountain, and Dr Alex Sampson. I met with Emeritus Professor Dadson at the stunning British Academy headquarters, and we discussed among other themes: Luso-Hispanic relations in the 15-17th centuries; the possible status of Castilian in Portugal during that time; the work of some historians on the crowns of Spain and Portugal; other prolific authors during the Iberian Union (e.g., Francisco de Portugal, Conde de Salinas); and Professor Dadson’s idea that Garcilaso’s poetry re-emerged in Spain via the bilingual Portuguese poets that wrote in Spanish and not because of Spaniards valuing Garcilaso’s poems. I met Emeritus Professor Pountain at the Henry Wellcome Gallery, another beautiful space (one that I already considered a favorite spot), where besides enjoying a classic afternoon English tea and a more-than enjoyable chat, we engaged in a very technical and lengthy discussion of: (ir)regular features in the Spanish poems written by bilingual Portuguese poets; linguistic variation in Renaissance Spain; Golden Age metrics and rhyme; the Nebrija vs. Valdés controversy; and the possible status of the contraction nel in Old and Classical Spanish. I met Dr Sampson in his UCL office, where before discussing my projects and him offering some really insightful suggestions and additional bibliographical references, we took a stroll through the once-a-week Farmer’s Market, where we purchased some tasty sweet goods from local bakers. Two members of the academic staff that I was not able to meet in person, but that I corresponded with, and that also offered some really helpful and pointed suggestions for further reading, were: Professor Julian Weiss and Dr Elena Carrera. I also connected with Dr Barry Taylor, librarian and curator of Early-Modern collections for the Iberian region at the British Library, and he supplied me with priceless information related to the printing of Castilian books in Portugal and with some articles that I was not familiar with that related to both of my projects. Those will be of great assistance in helping me contextualize my research questions.

Events outside the scope of my research agenda at the IMLR, but that are worth mentioning, were: meeting Professor Li Wei at the scenic Caffè Tropea in Russell Square, where we had an excellent conversation (and a really great meal!) regarding the British university system and possible sources of post-doctoral work in England; travelling to Manchester where I met with Professor Yaron Matras to discuss issues and methodological problems in the study of language contact; attending sessions at the IV Linguistics Student Research Conference held at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London; working on my doctoral dissertation on Spanish word order; and, drafting a portion of a future journal article related to Spanish in contact with English in the United States.

I also had time to self-reflect and enjoy the city of London, which never ceases to amaze me. I saw two fantastic performances at the Royal Opera House; enjoyed an acrobatics show at the Underbelly Festival; saw some family members and some old friends, and even made some new ones; celebrated a birthday (one of the big ones…); reconnected with electronic music; found a talented acupuncturist; bought books that I needed for my research that are not sold in the U.S. (thanks to Institute Manager Cathy Collins for hunting them down in the mailroom!); and most importantly and memorably, I experienced a very warm reception and genuine interest from practically everyone I got to meet. I will fondly remember my time as a Visiting Scholar at the School of Advanced Study, and I am grateful for having the unique opportunity to become part of this remarkable community of scholars. I truly enjoyed this entire experience and would do it all over again in a heartbeat. From my vantage point, this experience is what you make out of it. Regardless, whether you are considering it for a short-term or a long-term arrangement, I highly recommend anyone to apply for a research program at the SAS-IMLR. It is a great academic home and the process is really straight-forward. Best of all: you will never regret it!

Eduardo Ho-Fernández, Visiting Scholar IMLR, SAS (Jun-Jul 2019)

European Day of Languages 2019: German Translations in the Age of Brexit

On this European Day of Languages 2019, Angharad Mountford, PhD student at the IMLR, talks about German literary translations:

Despite our impending withdrawal from the EU, with all its separationist connotations and anti-European sentiment, it seems, from a book perspective at least, a great deal of the population is trying even harder to become more ‘European’. The year 2018 saw an impressive 5.5% rise in sales of translated fiction – and the majority of these are notably English-language translations of European texts. French books in translation stand at 17% of total volume sales, whilst Swedish and Norwegian translations also appear to be thriving. (1)

This blooming market for translations, however, is at odds with the reality of Modern Languages in the UK today. With the news that German as a subject is being cut from a large number of schools’ curriculums, and with fewer students taking up French and German for GCSE, at first glance, curiosity about the literature and culture of our neighbouring European counties appears to be dwindling. Similarly, Modern Languages graduate numbers are declining, resulting in the closure of university departments. Professor Nicola McLelland (University of Nottingham) estimates that in UK universities today, ‘the number of German units has halved from more than 80 in 2002 to fewer than 40’. (2)

Yet a recent surge in publications of English translations of German novels and their subsequent popularity, seems to paint a wholly more positive picture. Whether or not this is in part a reaction to the view that German is becoming a more sought-after language in terms of business and careers, or the news that many young people are looking to move to Berlin to avoid the UK post-Brexit, is questionable.

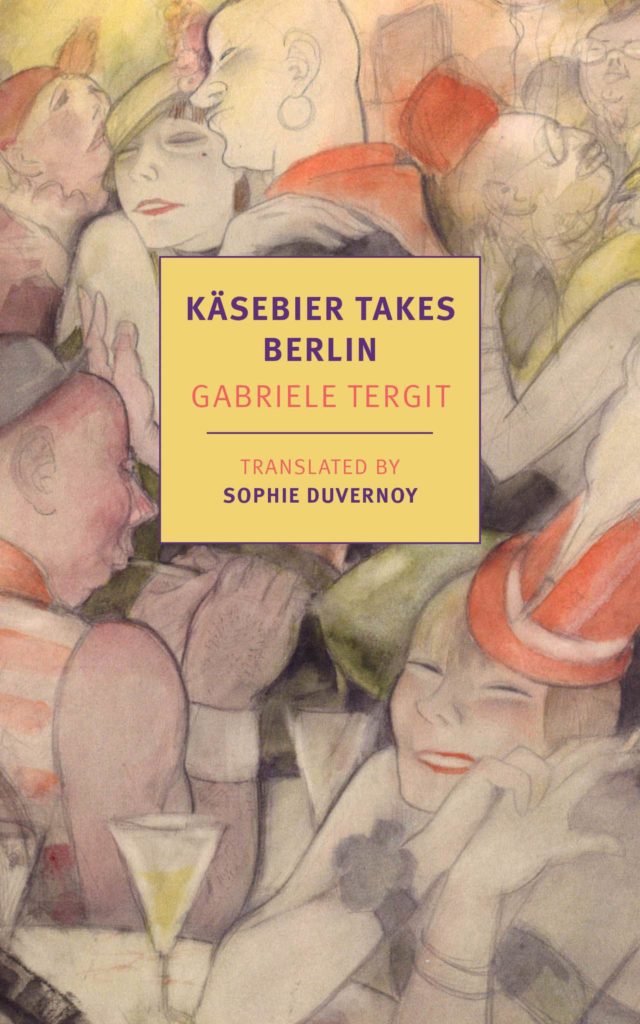

This year, certain English-language translations of German texts prove that German literature is back on the page when it comes to the UK book market. It is not only new books, however, that are being translated into English, but also a number of novels from the early 20th century that are only now making their debuts in the English market. Weimar writer Gabriele Tergit, who began her career in the 1920s whilst writing law court reports for a Berlin newspaper before turning her hand to novels, is a fairly unknown writer in Britain – even in Germany her name may not resonate with many people. This year saw the publication of the first English translation of Tergit’s 1920s novel Käsebier erobert den Kurfürstendamm (1931), translated by Sophie Duvernoy, with the title Käsebier takes Berlin (NYRB Classics, 2019). The novel, a tongue in cheek satire of the excesses of the Weimar Republic, introduces the humour and skill of Tergit’s writing to an English-speaking audience, and gives readers a snapshot of the cartoon-like world of working in a busy press department in the midst of Weimar Berlin. Nearly 100 years after its initial publication, this fine translation of an arguably ‘forgotten classic’ is hugely promising and will hopefully pave the way for a surge in other translations of German fiction.

Another notable translation is that of Austrian writer Ingeborg Bachmann’s only novel, Malina, published this summer by Penguin Modern Classics in its third, updated version, translated by Phillip Boehm. Originally published in 1971, just two years before Bachmann’s death, the novel was described by the author as an ‘imaginary autobiography’: it follows an unnamed woman writer living in Vienna, and her part in a love triangle that has deep psychological consequences.

Malina, however, is a novel that was also successful at the time of its publication. In contrast, Freido Lampe’s Am Rande der Nacht, was banned by the Nazis almost as soon as it had been published. Lampe, a disabled gay writer, penned his magic realism text in 1933, the same year that the Nazis removed it from sale due to its homosexual content and its depiction of an interracial marriage. Although Am Rande der Nacht was brought back into circulation in Germany a number of times since 1949, it was not until 1999 that a full, non-censored version was published. Now, twenty years later, an English-language readership can finally read the book. At the Edge of the Night, Simon Beattie’s translation of Lampe’s novel, was published by Hesperus Classics in February 2019.

These are of course just a handful of notable recent translations of German writing: take a look at any large bookseller’s ‘In Translation’ sections, and the sheer variety of texts is definitely a sign that there is indeed a growing market for books written in different languages. If this trend can filter through into more schools and universities prioritising languages, and to the public at large, then our appreciation for cultures other than our own can only grow.

Anghard Mountford, PhD Researcher, IMLR

(1) Research commissioned by Man Booker International Prize 2019, ‘Translated Fiction Continues to Grow | The Booker Prizes’ https://thebookerprizes.com/international/news/translated-fiction-continues-grow [accessed 19 September 2019].

(2) ‘We Need Languages Graduates to Steer Us through Our Post-Brexit Troubled Waters | Nicola McLelland | Education | The Guardian’ https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/jul/31/we-need-languages-graduates-to-steer-us-through-our-post-brexit-troubled-waters [accessed 19 September 2019].

The Taste of War: Values and Meanings of Food in WWII Italy and France

On a magnificent summer day on Friday 5 July 2019, at the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory, University of London, specialists in French and Italian history, literary and culture gathered together at ‘The Taste of War: Values and Meanings of Food in WWII Italy and France’ conference to discuss the material and imaginary importance of food in wartime Italy and France – countries characterised by similarities in terms of agricultural economies, Nazi occupation and Allies liberation, requisitions and black market. The day of study was very enriching and pleasant.

The conference opened with a keynote address by Kay Chadwick (Liverpool) and focused on food as a means of propaganda, used by both the Vichy regime and Free France in London. As an expert on radio propaganda in WWII France, Chadwick analysed the extensive Vichy radio propaganda and the BBC’s French Service, the main means of communication of Free France with metropolitan France, and reconstructed the dynamics of their food propaganda using a wide range of archival materials. She argued that given the food scarcity endured by the French population during the Nazi occupation, it was of vital importance for both Vichy and Free France to win the game of blame to ensure the solidarity of the population.

Karima Moyer-Nocchi (Siena-Roma Tor Vergata) looked at the psychological, political and national importance of bread in Italy from the fascist period to the high peak of the Resistance fight, between 1943 and 1945. Making use of documents of the time, recipe books and oral testimonies, Karima reconstructed a story of bread that goes from the mythical concept of white bread of ancient Rome to the pane bigio in the second part of the 1930s, and to pane unico – the brown government bread, the only legally available bread from 1941-.

With the deterioration of the living conditions during the war, witnesses narrated all sorts of coloured bread, from green to white bread, obtained with flour cut with clay, chalk, calcium carbonate or marble. It was the time of pane nero, that was, as Karima aptly puts it, ‘not just a statement about the color, but about the very animus of the people in a country destroyed by war’.

The paper by Paula Schwartz (Middlebury) discussed food protests in Paris, highlighting the fundamental role of women who led these riots. Crucial in the protests considered by Schwartz is the work of women’s groups of the French Communist Party. In my paper, I also discussed food protests that took place in various parts of Italy. In particular, I highlighted how the news of these protests was reported in the official and the clandestine issues of the women’s journal Noi donne. I contrasted these representations with the accounts of food and taste given by some women partisans in their memoirs, emphasizing the expression of an independent subjectivity that speaks of the personal transformation generated by the modification of social norms.

Teresa Fiore (Montclair) is working on a new project investigating food practices, military operations and human mobility in Sicily at the time of the Allied landing. She began her paper with an analysis of the food dynamics presented in Leonardo Sciascia’s novella ‘The American Aunt’ that in Fiore’s reading, illustrates how food becomes the metonym for the myth of America deriving from the experience of immigration in the earlier decades and reinforced by the US army landing.

As Sciascia rejects the black and white description of Sicilian poverty and American plenty, so Teresa Fiore allows a nuanced understanding of those food and cultural dynamics by complicating her reading of Sciascia’s novella, using recent interviews with Sicilians who experienced the 1943 landing. In these video-interviews memories of hunger intertwine with memories of food availability; more homogenous are the memories of the unusual food brought by the US troops.

While Sciascia’s novella emphasises the post-war American influence on food gifts that were sent by Italian American aunt, Fiore concludes her paper by looking at a more contemporary example of food memory: a dish by a Michel-star chef from Licata inspired to the K-ration of the US army, but paying tribute to the struggles of Sicilian mothers and grandmothers of the period.

Lisa Payne Ossian’s paper also focused on America, and in particular on its role in the effort against famine in the immediate aftermath of the war. She has worked on Herbert Hoover’s Famine Mission in Europe and has indeed taken us on a journey illustrating Truman’s reasons to appoint Hoover, and the extensive journey that took Hoover through Europe, and of course Italy and France, and on to India, China, Korea, Japan, and the Philippines.

Marta Brunelli and Anna Ascenzi (University of Macerata, IT), an historian of education and a social educator, specialised in school culture, have worked extensively on ‘material school culture’ a field of historical-educational research aimed at reconstructing the educational practices and cultural behaviours that really took places in schools and classrooms, and also on a gender approach to the history of education.

In particular, in their paper Brunelli and Ascenzi studied how the fascist regime put in practice what they call a ‘war pedagogy for women’, an educational system aimed to educate women in home economics, food hygiene and home production needs in wartime. They made use of a very large range of primary sources: from textbooks to journal’s magazine, from booklets of cooking and home management to booklets released by the Party’s propaganda office after Italy’s entry into the war and consisting in pocket-size manuals expressly addressed to housewives. In their presentation, Brunelli and Ascenzi underline a correspondence between the content and linguistic choices in these materials and the school educational guidelines, showing the complexity of the propagandistic and educational apparatus of the fascist regime up to 1940.

Maria Grazia Scrimieri (Côte d’Azur) has provided a cultural memory perspective by analysing the recurrence of food-related episodes in the novel by Renata Viganò, L’Agnese va a morire and exploring the recognition -or lack of recognition- of women’s work during the Resistance. She illustrated how food in this novel acquires several functions, but it is in Agnese’s participation at the Resistance, therefore in relation to her political actions that Scrimieri sees a link between the food-related images and the character.

Tommasina Gabriele (Wheaton College) provided a perfect conclusion to a day rich in comprehensive analyses and new perspectives. She looked at the socio-political critique of fascist and post-fascist Italy presented in Alba de Céspedes’s Dalla parte di lei (1949). Gabriele highlighted the protagonist’s material struggle to survive and her struggle to adhere to an unattainable ideal love relationship between equals.

In Gabriele’s analysis food becomes a symbol of patriarchal and matriarchal authority, class injustice, political subversion and queer desire. It is illuminating to see through Gabriele’s reading how in this novel the cipher of food allows the representation of women’s disillusionment after the war, and the passage from a patriarchal environment in the rural Abruzzi to the unrecognized women’s role in the urban post-war Rome. Gabriele demonstrates how food in de Cespedes’s novel acquires several functions that shed light on socio-political and gender critique.

The discussion following the papers and the interconnections in French and Italian cultures of the time suggest that the topic is a fruitful one for further analysis. We thank the University of London Cassal Fund and the Society of Italian Studies for funding the event.

Patrizia Sambuco (IMLR)

Global Portuguese 2019

Following the success of last year’s Global Portuguese symposium, a follow-on symposium was organised on Tuesday 18 June 2019, just a week after the National Day of Portugal (o Dia de Portugal). Given the large number of Portuguese diasporists in the UK, the event was a fitting occasion to remember Portugal’s achievements and impact globally, combining academic presentations and live performances.

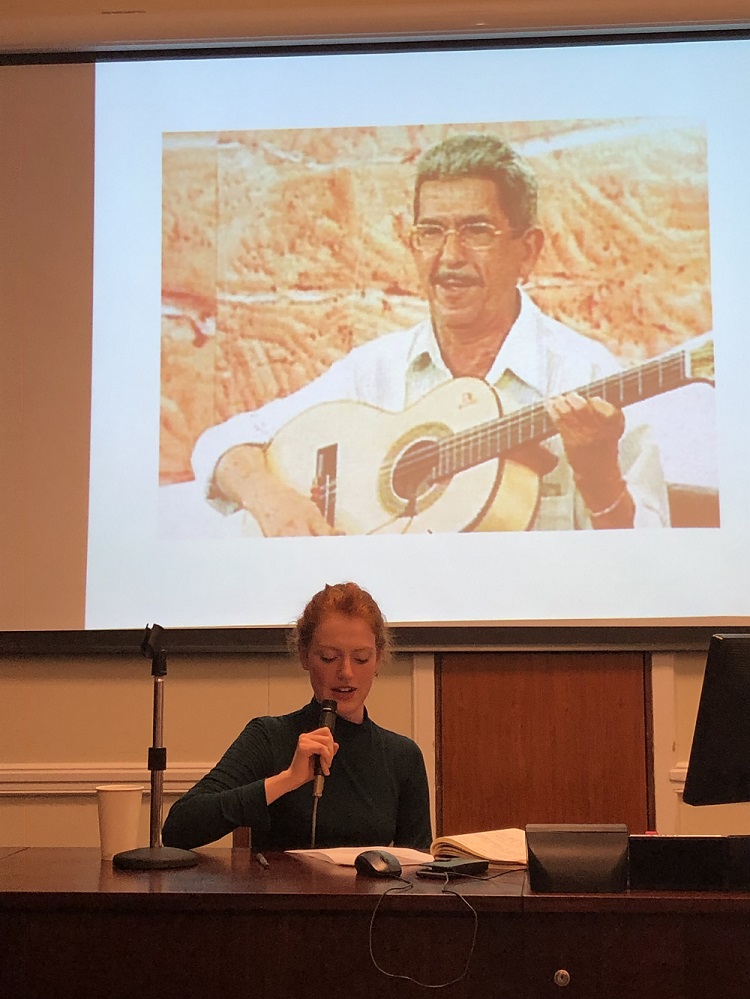

The symposium explored the global impact of Portuguese cultural imprints and transculturation. The papers presented cut across the first, second and third Portuguese empires and included Angola, Brazil, Mozambique and Sri Lanka and were spread across linguistics, literature, song, and religion. Dr Eric Morier-Genoud (Queens University, Belfast) spoke on the Catholic Church, the central institution in Portuguese history, and how religion was regulated during the Third empire, how the Catholic church re-organised as a consequence, and how it expanded in the 19th and 20th Century. He analysed the consequences of the Church expansion for the colonies and its inhabitants, and for the making of a Global Portuguese “Lusotopie”. Dr Shihan de Silva (School of Advanced Study) spoke on Sri Lanka Portuguese, the creolised Portuguese, once an important lingua franca, which has survived for over 500 years but is now endangered. She considered the linguistic situation of a speech community with African roots, in the Puttalam district, in the village of Sirambiyadiya, Northwestern Province, who had shifted to Sinhala. Dr Dorothée Boulanger and Andrzej Stuart-Thompson (University of Oxford) explored childhood in the works of two Angolan writers, José Luandino Vieira and Ondjaki. They analysed how childhood has become a privileged site of projection and construction of the new Angolan nation in the literature of the 1960s and the 1970s, when nationalist parties were fighting militarily, politically and culturally for Angola’s independence from Portuguese colonial domination. Connie Bloomfield (King’s College London) examined how popular poets from Northeast Brazil use classical Greek and Roman myth in their explorations of modernity and racial and class conflict. She looked first at cantoria from the turn of the 20th century, public improvised verse duels which contest individual status, then at printed folhetos or cordel from the early 20th century, finding that Graeco-Roman myths become important to local politics and facilitate the expression of covert popular counter-narratives. She argued that these poetries use European antiquity in a distinctly modern manner to enact social conflicts and community identity.

The presentations were followed by a live performance in the Chancellors Hall ranging from Portuguese folk, Cape Verdean and Brazilian by Natalia Cerqueira with introductions by Margarida Oldland, followed by the sentimental Goan Mando by Hemal Jayasuriya and Shihan de Silva, and ending with the rhythmically driven kaffrinhas and bailas of Sri Lanka by Samadi Galpayage, Hemal Jayasuriya and Shihan de Silva. A roundtable discussion followed after which the delegates networked over a glass of wine. The event was well attended and the diverse audience included staff from the European Commission, High Commissions, academics, researchers and members of the public.

The event was generously supported by the Coffin Fund and the Institute of Modern Languages Research.

Dr Shihan de Silva, School of Advanced Study