Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

‘What are you reading?’ ‘A testa d’aruta’: Translating Pasolini and Forgotten Pleasures, from María Bastianes

Coronavirus confinement arrived when I was in the middle of writing two articles, correcting the proofs of a book, organising a conference, planning three overseas trips, and booking train tickets to travel around the UK to give talks at different schools. All that went by the wayside. Like most people, I felt annoyed and impotent, which quickly transformed into fear and anxiety. These latter two feelings didn’t help with the sole task that I could do at home: using the books and materials I had salvaged from my office to continue with research.

In this winter of our discontent a friend, a translator and a poet, asked for my assistance with a project he was working on: a selection in Spanish of Pasolini’s poems on Rome. My contribution in this unequal partnership was my language skills (I won’t win any prizes as a translator and even less as a poet), and my Italian is not as great as I would like it to be – I’m not a native speaker, or even an Italianist. But there I was, spending my free time at weekends not going out but discussing the words and meanings of a language that is not my own.

A task that at first glance could seem as masochistic as following Pasolini’s free walks around Rome in times of lockdown (I love to wander by foot and I feared that the UK would replicate the more draconian rules on exercise taken by Italy or Spain) unexpectedly became the highlight of my week. Pasolini’s Rome is not the glamorous and ideal capital beloved of tourist postcards, but instead the Rome of the peripheries. As a testimone e patecipe (‘witness and participant’) the poet shows the reader the complex urban popular culture of the Roman lumpen proletariat: the world of the rissoso e umile (‘raucous and humble’) inhabitant of the borgate romane. This is the same world we can glimpse in some of his earlier (and best known) films, such as Mamma Roma or Accattone.

We started with the poem I just have quoted: Continuazione della serata a San Michele (‘The Evening Continues at San Michele’). Apart from the harsh and beautiful poetic insights into this Other Rome, translating Pasolini opened my eyes to something else. It had been a while, perhaps years, since I last had the time (and patience) to dedicate a full day to poetry by the only proper means of digestion: tasting every word and then discovering the place of every world in the final structure, before then locating the meaning of each and every world within the poetic edifice. Uncovering layers of beauty is as hard as it is rewarding. It is not how we tend to read in the twenty-first century. Perhaps that is why poetry is disappearing from even literature degrees. When I sat my first university exams, I felt held back by an inability to skim read and my tendency to digest everything as if I were preparing a poetic exegesis. Researchers are often rewarded more for writing and reading quickly. Perhaps the time is due for a correlative to a literary equivalent to the slow food movement, allowing us the time and space to just read slowly…

And then, the translation. Few things are as unproductive as translating poetry: you don’t get full credit for the result (you are not the author), only translation of theatre can be sometimes worse paid (if it is paid at all), and it takes a long time (much longer than prose). More than with any other Literature genre, if you don’t put in the groundwork, you will likely divert from the source text so much that the reader will be confused.

In Continuazione della serata a San Michele, there are balconies with girls watering something called testa d’aruta, I look in my online Italian-Spanish dictionary. Nothing. I look in my online monolingual Italian dictionary. Nothing. When all else fails, Saint Google to the rescue (or not). To my dismay, search results took me directly to the same verse of Pasolini’s poem, others to a poem by a late nineteenth century Neapolitan poet, Salvatore Di Giacomo, writing in the local dialect. Exactly the same image, a girl watering this damn testa d’aruta. I learn that aruta is a dialectal term for ruta (‘rue’), the quintessentially Mediterranean aromatic evergreen of yellow flowers. And testa is not the ‘head’ of the plant (that is what in standard Italian testa means), but the flowerpot. It is the antic meaning of the form testa, the Latin one: testa as ‘terracotta pots’. It has nothing to do with Pasolini’s poem, but I recall Monte Testaccio in Rome, that artificial mount (a roman spoil heap, in fact) composed of piles of fragments of testae, terracotta pots. I smile.

So a reference to Salvatore di Giacomo’s Neapolitan poem? I am excited, intellectually excited, but the context is strange (why in the middle of a poem on Rome?). I don’t want to run before I can walk, so I decide to share my discovery with native friends. I call a friend from Tuscany who dates a guy from a place near Neapolis, but the expression doesn’t ring a bell to them. I call someone else, who can’t help me either but promise to ask some elder members of her family (perhaps it is just a generational thing). Another friend from Sardinia who knows a native specialist in Roman dialect confirms it is not a form specific to that region. I call my mum in Argentina… just because…

By 9 pm I realise that I have spent almost 12 hours and enrolled a full army to attack just three words, not even half of a verse. I am quite sure it is a reference to Salvatore di Giacomo’s poem, or at least to that image of the girl watering a pot of rue, apparently common in Neapolitan lyric (in the meantime, I have found a popular song called A testa aruta, this one with many entries in Google). Some additional research reveals that Pasolini dedicated several works to dialectal poetry, had a particular interest in Neapolitan popular culture and was well familiarised with Di Giacomo poetry. I translate the three words and add a footnote… that my friend ends up wanting to delete… Still I am happy, like a child. The cat that got the cream.

This pace of life, this pace of work, it is a luxury, it is a pleasure long forgotten. It took me a pandemic and an incursion in a field that was not mine to remember that there are intellectual as well as physical orgasms. But perhaps a blog, a quintessentially twenty-first century mode of communication, is not the place to write about the pleasure of reading slowly… I would have done better to just shut up… and keep translating.

Dr María Bastianes, Marie Curie Research Fellow, University of Leeds

“The Stronger” Experiment

In ‘The Stronger Experiment’, Adriana Páramo Pérez filmed three teams of director-actress preparing for a role in their short film adaptation of August Strindberg’s play The Stronger. The goal was to see how the same text would come across differently depending on the creative process and the extent to which the characters they created would reflect patriarchal values.

The text

I chose the play The Stronger (1889) by August Strindberg because the apparent simplicity of the story, a monologue that happens in an encounter between two women, Character X (married) and Character Y (single), reveals a more complex reality. What starts as a casual conversation turns out to be about X confronting Y (who remains silent) because she knows Y has had an affair with her husband. X’s confrontation is a series of prejudices about the role of women in society. The way the text is written allows for many layers of interpretation but a question emerges from this: who really is the stronger (X as married woman and mother, or Y as single and independent)?

The short film rules

Lars Von Trier in his film The Five Obstructions (2003), created five different scenarios for auteur Jorgen Leth to re shoot his short film The Perfect Man (1967), hoping these restrictions would force Leth to abandon his mannered style. I also formulated a set of rules hoping that common limitations would allow for a variety of creations. Each team had the freedom to adapt the text and create the character as they wished but they had three rehearsal sessions to do this, and the short film had to be shot in one location, in one day and in a maximum of five shots.

The results

In ‘team A’ director Paul S. Mauch thought the play was not about the two women but they were an excuse to touch on the bigger issue of what it means to be within or outside the limits of society. However, actress Paula Rodríguez firmly believed that this was about the experience of being a woman. In the end, by presenting X in different states of mind they created a character that has contradictory views and that confronts the audience.

Director Femi Banjo in ‘team B’ gave voice to Character Y resulting in Laura Román playing two characters or, rather, the two sides of the same coin. Laura portrayed Y as being over confident showing her superiority over X, and presented X as a weak and rigid woman.

For ‘team C’, actress Monserrat Roig de Puig and myself (the director) X’s motivation was the betrayal, not just of her husband, but also of Y (as the text indicates they were friends).

The failure?

I saw in the three short films the teams created different characters and that they all addressed prejudices against women. However, I felt the experiment had failed because none of the teams (not even my own!) decided that character X should leave her husband. For me, I felt this would have been the ultimate liberation as the original text implies she feels oppressed by her husband.

In The Five Obstructions Von Trier reveals that he too has failed because the obstructions did not manage to break down Leth making him question himself and his methods. Instead, Von Trier admits that filming the conversations with Leth about how he dealt with the obstructions became a sort of therapy for himself (and not the other way around). In the same way, I realised this failure? had turned my experiment into something else. It was no longer about the final characters but about the process, about how these directors and actresses opened up a conversation. They saw that the prejudices Strindberg writes about in the nineteenth century in The Stronger still persist nowadays. What resonated with me the most was that the characters all felt that women are still expected to be mothers and wives. And so this experiment became the first step in my PhD journey about challenging the burdens of the motherhood experience.

Adriana Páramo Pérez, PhD student in Media Arts at Royal Holloway University, London

(Follow this link for a video essay about this project)

A New ‘Feminist’ Novel? Popular Narratives and the Pleasures of Reading

This CCWW conference was due to be held on 28 and 29 May 2020. Due to COVID-19 the conference had to be postponed to a later date. However we are delighted to bring you here short pieces from some of the speakers who were due to present their papers. This is a preview of the conference to come.

Dr Jezebel Mansell (University of Cambridge): A New ‘Feminist’ Novel? Popular Narratives and the Pleasures of Reading. As Joyful (and as useful) as Scotch Tape

Shelby Judge (University of Glasgow): The Rising Popularity of Contemporary Feminist Adaptations of Greek Myth

Rebecca Walker (University of St Andrews): ‘The Lying Life of Adults’: Ferrante and the Feminist Novel

Orsolya András (Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj, Romania): The Breath Against Silenced Fear

Dr Megan Henesy (Bournemouth University): ‘A Place of Women’: Herstory and Female Agency in Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s ‘The Mercies‘

Dr Françoise Campbell (Visiting Fellow, IMLR University of London): Reflections on Care Work and Female Subjectivity in Leïla Slimani’s ‘Chanson douce‘

Dr Ilse Born-Lechleitner (Johannes Kepler Universität Linz): My Journey Towards Female Speculative Fiction

Justine Muller (University of Louvain, Belgium): ‘Kiffe kiffe demain‘ (2004) by Faïza Guène: a feminist novel?

Dr Daria Forlenza (Independent Researcher): Reading the novel Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: An intersectional analysis

Sophie Benard (CURAPP-CNRS, Université de Picardie Jules Verne): Claire Richard’s Feminist Autobiopornography

Watch here a podcast preview from Mónica Ganhão (University of Lisbon): Writing Women for Nineteenth-century Readers: The Case of Herança de Lágrimas by Ana Plácido, and Dr Francesca Calamita (University of Virginia): Teaching and Researching on The Handmaid’s Tale and Luna Nera is a Feminist Issue

A New ‘Feminist’ Novel? Popular Narratives and the Pleasures of Reading. As Joyful (and as useful) as Scotch Tape

By Dr Jezebel Mansell (University of Cambridge)

Lucy Ellmann’s novel Ducks, Newburyport was released in 2019 to critical astonishment and acclaim. The work comes in at nine hundred and ninety-eight pages, and the primary narrative consists of a single-sentence interior monologue by an Ohioan baker and housewife. The sentence, punctuated by the phrase ‘the fact that’, encompasses her preoccupations with health, money, her husband and children, and is embedded with fragments of songs presumably playing on the radio, snippets of the musicals she watches as she bakes, and breaking news that, like push notifications on a phone, suddenly impinges upon her world.

In his review of Ducks, Newburyport for the London Review of Books, Jon Day draws a parallel between its unnamed protagonist’s dismissal of the Marie Kondo ‘does it spark joy?’ technique for keeping a minimalist home, and the usefulness of the question with regard to fiction. In Ellmann’s protagonist’s words: ‘Scotch tape doesn’t give me any joy, I don’t think, but sometimes you need some’ (Ellmann 2019: 469, author’s emphasis). While not all works of fiction are sources of unalloyed joy, their interpretations of the world in which we live are no less crucial.

The account of the protagonist of Ducks, Newburyport is repeatedly infringed upon by statistics and incidents of gun violence, school shootings, and other horrors. The novel might therefore be usefully considered as a feminist response to issues of violence and politics, in a vein that links Ellmann to writers such as Annie Ernaux or, in the world of film, Chantal Akerman, whose work pays attention to the minutiae of domestic life in the face of the violence and sorrows beyond the door, which threatens to ruin a carefully maintained peace.

Similarly, the way violence breaks into Ellmann’s protagonist’s psyche leads me to a consideration of the necessity of such representations within the genre (loosely speaking) of the new feminist novel. Wider settings of violence (primarily coded male, including sexual violence, gun violence, and the creation and upholding of laws that proscribe women’s autonomy) are shown here, radically, in terms of their effect on the domestic and interior spheres of women’s lives.

Ellmann’s protagonist refuses silence, ‘the numbness of muted beings’ frequently referred to in the narrative. Instead she provides a reflection upon the micro-histories of maternal and domestic lives, against a backdrop of broader anxieties, imagined and real, heard about and directly experienced, that impose on her thoughts. There is undoubtedly a profound sense of pleasure, if not sparks of joy, to be had in reading a voice at once attentive to the domestic and committed to speak out against the impact of violence on women’s daily lives.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Day, Jon (2019). ‘The Reality Effect’, in London Review of Books 41(23).

Ellmann, Lucy (2019). Ducks, Newburyport (Norwich: Galley Beggar Press).

The Rising Popularity of Contemporary Feminist Adaptations of Greek Myth

By Shelby Judge (University of Glasgow)

Madeline Miller’s Circe is undoubtedly both a ‘popular’ and ‘feminist’ novel. ‘Popularity’ can be a difficult concept to gauge, but whichever way you quantify it, Circe fits the bill. With over 134,000 copies sold worldwide, the novel is an international Number 1 bestseller (Wood 2019); Circe was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction and has been commissioned by HBO for an eight-part miniseries (Miller Online 2019). It has been met with an overwhelmingly positive response, and Miller’s online fanbase continues to grow around the world.

Circe is also a feminist novel. The eponymous protagonist is oppressed by the patriarchy, embodied by her father, Helios. He is the Titan of the Sun, cowed only by Zeus’ power, while his daughter is a human-voiced nymph, reflecting on how nymphs’ roles are to run away, be pursued, and get raped. He alternates sitting on his obsidian throne and astride his golden chariot, while his daughter crouches obediently at his feet. That is, until she rebels and is punished, cast down to the earth and imprisoned on Aiaia. The novel follows Circe’s journey, as she labours to learn witchcraft, turning lions into pets and men into pigs, and weaves a rich tapestry of life — of which, Odysseus is only one part. In the Odyssey, Circe is only relevant where her story intersects with Odysseus’ (namely, in Book 10); in Circe, Odysseus is only one fraction of Circe’s immortal life.

This novel, while innovative and original, is not, however, the only one of its kind. Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, Ursula Le Guin’s Lavinia, and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls are all examples of the same phenomena: contemporary female authors adapting Greek myth for feminist purposes. These authors use ancient myths to narrate latter-day life, reinvigorating and re-politicising these tales to highlight a myriad of modern issues that women face, including women’s treatment in wartime, #MeToo, social inequalities, and domestic labour.

Again, though, this generation of women writers is not the first to look to myth for a source text. Think of a wall, but with books instead of bricks. That is what is happening now, with feminist authors using Greek myth as the connective cement — each woman places their contribution upon the pile, building up from the foundational contributions of French post-structuralists such as Hélène Cixous, Luce Irigaray, and Julia Kristeva.

Why is it, then, that these authors choose to return to stories already told, myths already known? Theories of adaptation (Sanders 2006; Hutcheon 2006) tell us there is a pleasure to rewriting and rereading, a specific joy to re-experiencing something you thought you already knew, but finding it reinvigorated, supplemented, innovated. It is this uncanny familiarity that makes feminist adaptations of myth popular in contemporary novels.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Miller, Madeline, Circe, (London & New York: Bloomsbury, 2018)

Wood, Heloise, 2 August 2019. ‘Miller’s Circe snared for HBO drama series’, The Bookseller <https://www.thebookseller.com/news/millers-circe-snared-hbo-drama-series-1051491> [last accessed 18 May 2020]

Sanders, Julie, Adaptation and Appropriation, (London: Routledge 2006)

Hutcheon, Linda, A Theory of Adaptation, (London: Routledge 2006)

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

Shelby Judge is a second year English Literature PhD student at the University of Glasgow. Her thesis topic is “Exploring contemporary women writers’ adaptation of myth for feminist purposes”. In this thesis, Shelby is researching what impact contemporary adaptations of Greek myth can have upon the feminist movement. Shelby’s overarching research interests are in feminist and queer theory and contemporary British and American women’s fiction. Shelby also runs a PhD-related blog: TheShelbiad.blogspot.com

The Lying Life of Adults: Ferrante and the Feminist Novel

By Rebecca Walker (University of St Andrews)

‘Two years before he left us my father said to my mother that I was very ugly’ (9). (1) Thus begins the latest novel by Elena Ferrante. ‘This is how, at twelve years old,’ the narrator Giovanna explains, ‘I learned from my father’s voice, choked by the effort of speaking softly, that I was becoming like his sister, a woman in whom, for as long as I could remember, I had heard him say that ugliness and wickedness were found in perfect combination’ (12). Giovanna’s life is transformed by a growing obsession with these words uttered by her father: she must find the mysterious zia Vittoria in order to verify the resemblance he has identified, and to ascertain whether, like this woman, she too is one of the ‘bad’ ones in whom physical and moral offensiveness are combined. As the teenager journeys back and forth from the affluent and erudite but shallow world of the Vomero on high to the industrial suburbs of working class Naples below, hers is not only a quest for answers, but an attempt to establish the contours of the self at a time when its margins are particularly vulnerable to rupture.

The Lying Life of Adults (2020) – where Giovanna acts as a vector for the reception, generation, and transmission of negative emotion – is a fresh example of a trend in Ferrante’s literary production where she engages deeply with what it means for women to ‘feel bad’. Her narratives zoom in on those visceral and painful aspects of emotional life such as anger, shame, jealousy, and self-loathing which we are encouraged to suppress, but which are necessary for transparent and authentic self-expression. In one of the personal reflections in Incidental Inventions (2019), a collection of her 2018 Guardian columns, she states that ‘I have learned that bad feelings are inevitable; if we want to be honest with ourselves, we have to confess them. It’s a matter of discipline’ (69). In Ferrante, moreover, one can view bad feelings as both the product of the truncated possibilities presented to women in patriarchal paradigms, and as having a feminist potential which is politically and personally resonant.

Her newest offering presents this more clearly than ever. The pain associated with what Giovanna has learned by the novel’s close – that all of us lie and are ‘ugly’ in some way, that appearances deceive, that the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ are not neatly divided – is also the means by which she is able to name and resist that same negativity which threatens to consume her. Giovanna’s coming of age story, like that of Elena and Lila in the Neapolitan Novels, reclaims the territory of the ambivalent, the violent, and the unsayable, suturing readers into empathetic identification with these literary women, and creating a space from which we can reclaim our own bad feelings and harness their creative potential. This is the feminist novel at its most potent: naming our disenchantment in order to mitigate its shattering effects.

(1) In advance of the publication of Ann Goldstein’s English language edition in June 2020, translations are my own.

The Breath Against Silenced Fear

By Orsolya András (Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj, Romania)

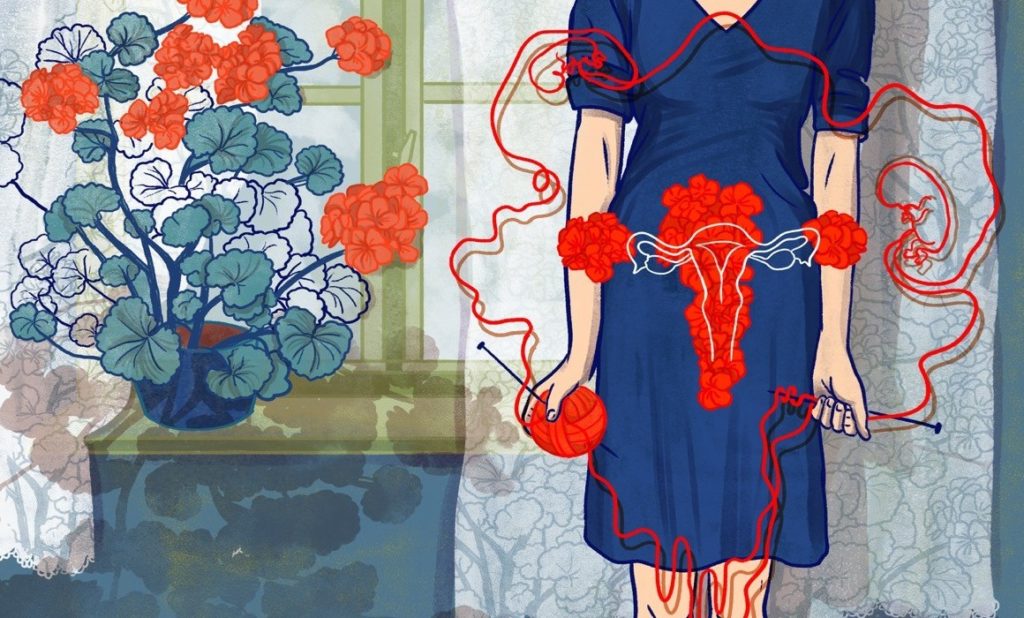

Corina Sabău’s novel Și se auzeau greierii [And you could hear the crickets] (2019) is the story of an illegal abortion taking place in Romania of the 1980s. Sabău’s narrative is full of tension, absorbing the reader in a personal drama that reflects social problems which remain burning issues in Romania. Sabău’s novel was welcome by critics, being called a short but intense work, a representative text for the situation of women under dictatorship – a topic which received special attention in 2019, thirty years after the fall of the regime. It has been received with enthusiasm by some readers, especially because of its ability to wake their empathy; here I will try to explain why many people could resonate with this novel.

A postsocialist Handmaid’s Tale

Beyond the image of independent women celebrated by socialist propaganda, the dictatorship established a state-run patriarchy (1) in Romania. This included the restriction of sexual and reproductive rights; it is estimated that ca. 10.000 women lost their lives because of unsafe abortions.

Corina Sabău writes about this situation with excruciating honesty: “you knew that the foetus in your womb was state property” [my translation] – a policeman tells the main character Ecaterina, objectifying her body and paralyzing her will. The novel describes the humiliation and trauma of women subjected to forced gynaecological check-ups, the disgust and desperation provoked by “home remedies”, such as boiling water, quinine or oleander leaves, the intervention of more or less qualified health workers causing abortions, infertility, death or the mysterious disappearance of women. These scenes have a powerful emotional impact, giving a voice to the silenced victims of the regime, suffocated in a culture of unbreakable taboos. The novel’s popularity is not only due to the processing of a suppressed past, but also to the fact that it deals with phenomena such as sexism, the lack of sexual education and the collective shame surrounding reproductive health, issues which still cause serious problems in today’s Romania. (2)

Feminist writing, identity and empowerment

Sabău’s character Ecaterina is in constant search of her own identity. Fleeing from poverty and a toxic family, she becomes a self-made engineer and tries to be a perfect worker, submitting herself to the system’s rules and expectations. She hopes that her marriage could redefine her identity: “I never imagined that my name could sound like this, and with my name pronounced by him I started a new life” [my translation]. Depending on her husband’s validation, she artificially imposes another role onto herself, the one of a loved wife. She soon sees him growing distant and cold, which pushes her to perform an abortion at home. At the end of the novel, we see her identity disappearing behind stereotypes and accusations.

The novel’s long sentences, flowing like an unstoppable river, are Ecaterina’s way of protecting herself from nameless fear and imminent danger. The reader follows her breathlessly, getting involved in this rhythm, starting to take the deep breaths of a story standing against panic, exploitation and silence. Feminist writing can show gender-based violence, or can go a step further and construct the identity of an empowered woman who has overcome trauma and is no longer a victim. (3) Ecaterina can tell her own story, the agency of her language giving her power. Her teenage daughter Sonia, who narrates the last chapters of the novel after Ecaterina’s death, breaks the mould. In the final scene, at her mother’s funeral, she looks bravely up into the eyes of a man representing the oppressive power. Sonia is part of the next generation, raising her voice for women’s rights.

(1) This dissonance in the socialist system is described in Birth of Democratic Citizenship: Women and Power in Modern Romania by Maria Bucur and Mihaela Miroiu (Indiana University Press, 2018).

(2) Adriana Radu, founder of the sexual education platform Sexul vs. barza [Sex vs. the Stork], showed in her recent research the dramatic consequences of the lack of sexual education in Romania.

(3) Female authors from Romania and the Republic of Moldova, such as Medeea Iancu and Nicoleta Esinencu, practise very empowering feminist writing.

‘A Place of Women’: Herstory and Female Agency in Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s The Mercies

By Dr Megan Henesy (Bournemouth University)

The Mercies is a historical novel set on the Norwegian island of Vardø which begins on Christmas Eve 1617, the day when all the men of the island are killed by a storm while fishing. The women of Vardø are left to fend for themselves, taking on the men’s work as well as their own domestic tasks, and reshaping the community following their collective tragedy. Eighteen months later, the arrival of the newly appointed Commissioner of Vardø, Absolom Cornet, challenges the women’s new way of life as he launches a period of oppression and instigates a witch hunt which leads to trials and executions.

The real events that inspired this novel, the tragic storm of 1617 and the witch trials of 1621 arguably make The Mercies an example of ‘herstory’. Herstories ‘bear witness to and speak out about traumatic experience’, while also challenging ‘official versions of patriarchal history’ (Pellicer-Ortin and Andermahr, 2013, pp. 4-5), and this novel does so through its presentation of recognised feminist tropes such as female resistance, female sexuality, patriarchal violence, and religious tyranny. The novel presents a place and time in which there is a fine balance between religious fervour and practical survival: some of Vardø’s women see indicators of the Devil’s work in omens such as a whale swimming upside down, a tern wheeling in figures of eight (p. 15), while others, including the protagonist Maren, become drawn to the autonomy and agency offered in their new roles:

Maren feels a change, a turning amongst the women. Something darker is growing, and she finds it in herself too. She is less and less interested in what [the pastor] has to say, and more consumed by her work: fishing, chopping wood, readying the fields. In kirke, she finds she has drifted, like an untethered boat, and her mind is out at sea with oars in her hands and an ache in her arms. (p. 46)

Millwood Hargrave’s novel plays with concepts of female-centric storytelling and language, exploring the way that events such as the storm become embedded in the collective memory of these women by their retelling of the story ‘through many tongues until its rough, difficult edges are worn smooth as sea glass’ (p. 48). The women are illiterate and so pass knowledge to each other through speech, while the statuses of the few male characters are defined by official letters bearing seals and tassels which they pass between each other. Thus, the novel generates empathy in the readers, reminding us that these true historic events were documented by men of letters, not the illiterate women of Vardø, and it gives us a chance to explore what these women’s stories might have been: what they may have felt, how they survived, and how they experienced pleasure and grief in a place so far removed from the rest of the world.

Works cited

Millwood Hargrave, Kiran (2020). The Mercies. London: Picador.

Pellicer-Ortin, S. and Andermahr, S. (2013). Trauma Narratives and Herstory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Reflections on Care Work and Female Subjectivity in Leïla Slimani’s Chanson douce

By Dr Françoise Campbell (Visiting Fellow, IMLR University of London)

In the wake of the global Covid19 pandemic, Forbes magazine ran an article with the following title: ‘What do countries with the best Coronavirus responses have in common? Women leaders’ (Wittenberg-Cox 2020). Citing qualities such as ‘empathy’, ‘care’ and even ‘love’, this somewhat tokenisticpiece highlights the deeply rooted association between women and care that has long existed in Western society. However, despite the bold claims of its title, this article reveals more about the prevailing gender inequalities surrounding care work than political power. As the article ‘Le monde d’après sera féministe ou ne sera pas’ [‘the next world will be feminist or won’t be at all’], published in the French political magazine Politis, states of our current climate: ‘Les femmes subissent une double peine: celle d’être à la fois les plus touchées par les conséquences de la pandémie et les plus impliquées, en première ligne’ [‘Women are serving a double sentence: they are at once the most affected by the consequences of the pandemic and the most involved, on the front line’] (Collectif, 2020). Representing 78% of health sector workers in France (ibid.), women are more numerous across the wide spectrum of professional and non-professional care work, which despite their increasing social importance remain, for the most part, devalued, invisible and underpaid.

The fraught association between female subjectivity and care work forms the basis of Leïla Slimani’s best-selling novel Chanson douce, for which she was awarded the Prix Goncourt in 2016. Translated into English as Lullaby in 2018, this highly popular novel draws the curtain back from the serene exterior of domestic life to cast new light on caring practices. As Slimani explains in an interview with France Culture, ‘Je voulais essayer de montrer que l’espace domestique était un espace politique’ [‘I wanted to try and show that the domestic sphere was a political arena’] (Slimani, 2019).

Following the parallel and intersecting lives of a Parisian family and their nanny, Louise, the narrative revolves around the act of taking care of others and the need for care experienced by each character which, having been left unmet, leads to tragedy. At the end of the narrative, in an act of desperation, Louise murders the two children under her care. Chanson douce dramatizes the tensions of caring relationships, from the ambivalent condition of the working mother to the innate hypocrisies maintaining the power dynamic between the nanny and her employer. Although Slimani does not attempt to justify Louise’s crimes, the novel’s irresolute ending calls for further reflection on the relationship between the characters and the nature of care across the narrative.

The great success of Chanson douce, despite its troubling subject matter, can perhaps be attributed to strikingly large proportion of women affected by care work, within and outside of the professional sector, which has only risen since the pandemic. In Chanson douce, the portrayal of care is anything but benign. Rather, Slimani’s novel allows the reader to question the complex processes of interdependence through which class struggle, economics and gender collide to reveal the political nature of care work and its continued impact on female subjectivity.

Works cited:

Avivah Wittenberg-Cox, ‘What do countries with the best Coronavirus responses have in common? Women leaders’, Forbes, 13/04/2020.

Collectif, ’Le monde d’après sera féministe ou ne sera pas’, Politis, 9/05/2020.

Interview with Leïla Slimani, “Dans Chanson douce, je voulais montrer que l’espace domestique est politique”, France Culture, 14/03/2019,

Slimani, Leïla, Chanson douce, Paris: Gallimard, 2016.

My Journey Towards Female Speculative Fiction

By Dr Ilse Born-Lechleitner (Johannes Kepler Universität Linz)

When I started to study English literature (which was quite a while ago), female speculative fiction was simply not on the agenda. Our reading lists for the various lectures and seminars contained Literature – works from the established Canon of English and American writing, predominantly written by men, though we did wander through the ‘Austen peaks, the Brontë cliffs, the Eliot range and the Woolf hills’, as Elaine Showalter (2009, IX) puts it. Discussions of later 20th century literature centred around Orwell and Huxley, and maybe the odd short story by Ray Bradbury or Doris Lessing (but not, of course, The Golden Notebook (1962)).

So, when I discovered Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale (1985) on my own, it provided an entrance into a dystopian world that was entirely believable, all the more so since, as Atwood famously claims, nothing in the book was invented. This has made Atwood’s novel so horrifyingly apposite even today and sanctioned the recent appeal and popularity of not only her work but also that of other female authors, both in print form and in their televised versions. The Handmaid’s Tale has opened the path into the world of speculative fiction, an umbrella term for utopia, dystopia, and science fiction, in which female writers explore, among other avenues, the boundaries of gender and possible ways of transcending its rigid, culturally constructed roles. In a setting that makes the everyday seem strange as it is (sometimes just a little) ahead of our time, female writers highlight female inequality and oppression in present society and force their readers to explore and re-evaluate their understanding of sexuality and their pre-conceived notions of gender by showing its social constructedness, simultaneously transcending the feminist point of view to explore what it means to be a human being.

What could a world look like that has transcended the gender binary? Ursula Le Guin gives an intriguing answer in The Left Hand of Darkness (1969): in the ambisexual world of Gethen/Winter, ‘anyone can turn his hand to anything’ because ‘everyone between seventeen and thirty-five or so is liable to be … tied down to childbearing’. Also, there is ‘no division of humanity into strong and weak halves, protective/protected, dominant/submissive, owner/chattel, active/passive’ (p. 100), as ‘[o]ne is respected and judged only as a human being’ (p. 101).

Another question that female speculative fiction has explored from the beginning is whether a society ruled by women would be a better society than one ruled by men. The classic Herland (Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 1915) provides a rather too idealistic answer. More recently, Naomi Alderman in The Power (2016) shows that any society not based on equality (between the sexes, between races) will suppress whoever is less powerful. In the main story line of the novel, Alderman creates a world very close to the one we live in — but women have developed the ability to deliver electric shocks, and are, suddenly, the ‘stronger sex’. In her frame story, set some 5000 years later, the female-dominated society that has evolved looks suspiciously like a mirror of our present, male-dominated one, with the (female) mentor of the fictional (male) author of the book advising him to publish under a female pseudonym to avoid the label of ‘men’s literature’ (a reminder that female writers, also of speculative fiction, have had, and still need, to hide behind male pseudonyms or their initials).

Going through my lecture notes on the 19th century, I discover that I wrote READ! next to the professor’s brief discussion of Frankenstein, only I never did back then because literature needed to depict real life and its complexities, did it not? But does it? Literature needs to be inspiring and thought-provoking, to set our minds free, to push boundaries, to allow us to explore the what-ifs, not only the that’s-what-it’s-like, and speculative fiction, in its many forms, does exactly that.

Works cited

Alderman, Naomi. The Power. Penguin Books 2016.

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. Virago Press, 1985.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Left Hand of Darkness. 50th anniversary edition. ACE New York 1969/2019.

Lessing, Doris. The Golden Notebook. Michael Joseph, 1962.

Perkins Gilman, Charlotte. Herland. Nasty Pankova, 2020 [1915].

Shelly, Mary. Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus. Gutenberg ebook, 2018 [1818].

Showalter, Elaine. A Literature of Their Own. From Charlotte Brontë to Doris Lessing. Revised and expanded edition, Virago Press 2009.

Kiffe kiffe demain (2004) by Faïza Guène: a feminist novel?

By Justine Muller (University of Louvain, Belgium)

Faïza Guène published her first novel Kiffe kiffe demain in 2004, at the age of nineteen. More than four hundred thousand copies of the novel were sold in France, it was translated into twenty-six languages and has had several reissues. The novel was released in a particular social context where the suburbs were at the centre of attention. It was published two years after Samira Bellil’s testimony novel Dans l’enfer des tournantes and the death of Sohane Benziane who was burned alive by her former boyfriend, and one year after the creation of the French non-profit organisation ‘Ni putes ni soumises’. This organisation was bornfollowing the ‘Marche des femmes des quartiers pour l’égalité et contre le ghetto’ which was prompted by these two major events. (1)

In this context, Faïza Guène offers a different image of the Parisian suburbs and the Maghrebi women of first- and second-generation immigrants who live within it. Her book editor Isabelle Seguin was interested in her ‘optimistic vision’: ‘for once we weren’t hearing about rapes, gang rapes, or things like that’.(2) However, she does not give us an idealised vision of life in the French suburbs. The author tackles major issues such as that of family and marriage, poverty, gender discrimination and French racism, but she does so through the character of Doria who is above all a fifteen-year-old teenager with a strong personality who recounts in a youthful language and with a lot of humour her daily life in a Parisian suburb.

Doria lives with her mother who works as a cleaner in a Formula-One-Themed motel run by a violent and disrespectful man. Her father has left for Morocco to marry a younger wife with whom he hopes to have a son. She begins her story expressing the weight of being born a girl: ‘Dad, he wanted a son. […] But he only got one kid and it was a girl’.(3) The two women also face daily racist comments as well as condescending gazes from certain people such as the social workers who look at them with a ‘superior air’(4) and treat them like ‘random file numbers’.(5) Yet, this novel is also a story of empowerment. The mother, after years in France, starts a literacy training and finds a new job that makes her happier: ‘She’s free, literate (or nearly), and she didn’t even need a therapy to get it all worked out’,(6) notes Doria. The teenager does not know what she wants to do as a job but she refuses ‘to end up behind a fast-food register […] And getting torn up by [her] supervisor’.(7) At the end of the book, she begins to dream of getting into politics one day: ‘I’ll lead the uprising in the Paradise Estate. […] It will be an intelligent revolution, with no violence, where every person stands up to be heard’.(8)

From a feminist perspective, Doria and her mother, but also many other female characters who are depicted in the novel, give a voice to women who want to get out of the victim rut and act as a model of empowerment. Thereby, by choosing a popular and colloquial language which facilitates the identification of the readers with the character of Doria, Faïza Guène succeeds in discussing contemporary political issues and promotes the readers’ own empowerment. In this way, the novel offers a reading experience which is at the same time pleasurable and empowering.

(1) Fadela Amara, Ni putes ni soumises, Paris, La Découverte, 2004, p. 6.

(2) In Kathryn A. Kleppinger, Branding the ‘Beur’ Author: Minority Writing and the Media in France, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 205.

(3) Faïza Guène, Kiffe kiffe demain, Paris, Livre de Poche, 2005, p. 10 [all translations from this novel are mine].

(4) Ibid., p. 67.

(5) Ibid., p. 113.

(6) Ibid., p. 188.

(7) Ibid., p. 24.

(8) Ibid., p. 189.

Reading the novel Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: An intersectional analysis

By Dr Daria Forlenza (Independent Researcher)

Intersectionality

The theory of intersectionality has made scholars reflect on the exclusion of subjects marginalised by feminist theory and the impact that this exclusion has caused in practice (Crenshaw, 1989; Nash, 2008). In particular it has highlighted black women’s complex subjectivity and the different levels of discrimination that they face on account of race as well as gender. A new kind of feminism has emerged which gives voice to black women, their stories and experiences and conceptualizes their identity in history.

Intersectional feminist theory draws on literature because literature has the power to disrupt stereotypes, to bring to the centre previously ignored subjects, to engage a broad readership, and shape new social and cultural representations.

An intersectional analysis of Americanah and the reading process

The intersectional focus of Adichie’s 2013 novel is visible in its interweaving of the themes of gender, ethnicity, and migration with the identitarian challenges encountered by Africans in the United States.

The story is set in Nigeria and in the USA. Ifemelu, the protagonist, decides to leave Nigeria for the USA to find opportunities for a better life, but she struggles to integrate in the host context because of her ethnicity. Similarly, Obinze, her Nigerian boyfriend, goes to the UK and struggles to integrate in the new context.

The storytelling is entrusted to Ifemelu and Obinze. The narrators’ linguistic competence, both verbal and non-verbal, is a device that heightens the reader’s reflection on the characters’ actions and perspectives. The narrative focuses on communication amongst characters and emphasises the linguistic distance between the Igbo language and English. Igbo identifies the characters, their story, their culture and is, thus, used by Adichie to highlight ethnic identity. The readers are drawn to the many Igbo words, Igbo linguistic patterns and Igbo-inflected anecdotes. During the course of the novel they become involved in the characters’ speech flow and Igbo sounds and become acquainted with the meaning of the words. Finally, they are able to decode the indigenous language and make sense of the world behind it.

In order to convey her protagonists’ feelings for their homeland, Adichie uses flashbacks that take us back to Ifemelu’s and Obinze’s childhood and youth. The shifts to the memories create a sense of ‘mobile’ identity: a feeling of being ‘in between’ different realities and a shifting sense of belonging. Even after living in the USA for many years, the feeling of alienation never abandons Ifemelu.

Narratives of migration often end with integration in the host country, accompanied by a constant presence of nostalgia for the lost homeland. Adichie’s story ends with Ifemelu’s return to Nigeria, a return that signifies a rejection of the white western narrative in favour of a developing African diaspora consciousness. Adichie tells us that to return home is not always the consequence of a failed migration but of the need to go back to one’s roots.

However, Ifemelu’s first impressions of Nigeria register a sense of loss and wonder: ‘She had grown up knowing all the bus stops and the side streets, understanding the cryptic codes of conductors and the body language of street hawkers. Now, she struggled to grasp the unspoken. When had shopkeepers become so rude? Had buildings in Lagos always had this patina of decay? And when did it become a city of people quick to beg and too enamored of free things?’ (Americanah, p. 475). The term ‘Americanah’ asks the reader to engage with a new ethnic code, Nigerians who return to their homeland after having migrated to the United States: ‘“Americanah!” Ranyinudo teased her often. “You are looking at things with American eyes. But the problem is that you are not even a real Americanah. At least if you had an American accent, we would tolerate your complaining!’ (Americanah, pp. 475-76).

Adichie constructs a plurality of black women (and men), with different roles, beliefs, and desires: Ifemelu, a woman who does not want to depend on men, is portrayed alongside Kosi, Obinze’s wife, a more traditional woman who wants to get married. Adichie’s aim is to disrupt stereotypes which affect black communities and especially black women, and to give a fair representation of what it means to be black in contemporary society.

Works cited

Adichie, Ngozi Chimamanda (2013) Americanah. New York: Anchor Books.

Crenshaw, K. (1989) ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics’. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1: 139-167.

Nash, C. J. (2008) ‘Re-thinking Intersectionality’. Feminist Review, 89 (1): 1-15.

Biography

Daria Forlenza grew up in Naples, Italy, where she graduated in Political Science from the University of Naples Federico II. She obtained her PhD in Rome, where she currently lives. She conducted part of her PhD research at SOAS, University of London. Here she developed a research project on ‘Integration and Immigration: The Ethnic Press in the City of Rome and London’. She has worked as a researcher for a number of Research Institutes in Rome, analysing migration patterns. She has also worked on pedagogical approaches to teaching Italian and teaches in high school as well as Italian classes for non-native speakers. Alongside research and teaching, she has a keen interest in writing and journalism.

Claire Richard’s Feminist Autobiopornography

By Sophie Benard (CURAPP-CNRS, Université de Picardie Jules Verne, Le Monde des livres, Le Matricule des anges, A.O.C.)

Claire Richard was born in 1985. She was able to follow the venereal woes of Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky and watch American democracy get sick of them. But she witnessed something even more obscene and scabrous. She witnessed the birth of YouPorn, the most sprawling platform to offer an infinite number of free pornographic videos from individuals and professionals.

Les Chemins de désir, published in France in March 2019, aims precisely at giving an account of the ‘pornographic life’ of their author. Neither her sex life nor her fantasy life, but her ‘porn life’, deeply determined by the discovery of YouPorn. From her first emotions as a young girl in front of licentious comic book images to the most perilous explorations of the Internet’s depths.

This ‘autobiopornographic’ text — to use Guillaume Dustan’s term for the autobiographical trilogy of his ‘sexual self’ — finds its value in the review and critical examination of the political and social problems of pornographic consumption. To feel resolutely feminist while being ‘excited by stories where women are treated like bitches’ (p. 51). To fantasize about lesbian scenes while maintaining an exclusively heterosexual love life. To vouch for the working conditions and salaries of the actors and actresses by the mere act of viewing. With an intelligence as greedy as the fantasy appetite she describes, the author confronts these agreed-upon moral difficulties in a brilliantly unseemly and never moralizing manner.

Richard’s natural and instinctive writing in the first person is not only at the service of the intimate narrative. There are many ingenious literary devices that seek to transcribe the intertwining of the private and the political. Lists of pornographic tags are thus introduced into the text with the same typography as the haunting questions of the author’s intelligence posed to the woman who abandons herself to her libidinous research ― the practice of pornography seems to divide her. And this interweaving between the character and the intradiegetic author is such that the pornographic fantasies shift, as the narrator turns away from the classic staging of dominated women to the erotic spectacle of female masturbation in its own right:

As if to stay on YouPorn knowing the conditions under which women work there, the only solution was to watch a woman choose for herself the conditions of her pleasure, the rhythm, the speed and the position in which she wants to come. (p. 65)

The text ends with renewed fantasies reconciled with feminism by replacing videos with audio fiction from the Gone Wild Audio website. Freed from the visual tyranny of pornographic images, the narrator ends up abandoning herself, with her eyes closed, to the stories told and acted out. And this reveals that the author has conceived her text in a double way: Les Chemins de désir is both a printed book and a podcast (Arte Radio) in which Claire Richard herself whispers to the listeners her paths of desire, in French, in six episodes of 10 to 20 minutes each. At a time when the podcast is becoming increasingly popular, this choice of declining her text in two formats lends the author great popularity, in addition to offering her readers great potential of identification with audio fantasies.

Works cited

Claire Richard, Les Chemins de désir, Paris: Seuil, 2019 [all translations are my own]

Guillaume Dustan, Oeuvres I, Dans ma chambre, Je sors ce soir, Plus fort que moi, Paris : P.O.L., 2013.

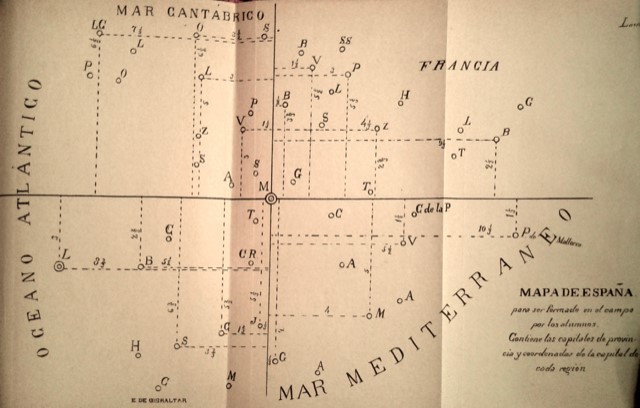

Children’s Play in Times of Crisis: The Language of Health in Spain from ‘Colonias’ to COVID-19

‘Donde no entra el aire y el sol entra el médico’ – Spanish saying

It wasn’t long before activists began raising their voices. Children, confined to crowded apartments, deprived of sunlight and fresh air, lacked proper space to learn and play. Reformers debated alternatives and models from neighbouring countries, while pamphlets and newspapers covered their efforts to create spaces for Spain’s children to move and grow.

More than a century has passed since the height of Spain’s efforts to transform urban children’s health through public health measures. Decrying the status quo, educationalists and policymakers joined reformers around the world in a transnational movement for open-air schools, pedagogies of play and contact with the natural world. As one doctor argued in 1909, children’s development relied on three things: “aire, luz y movimiento”, all woefully missing in their homes and in their schools, and particularly in the poorest neighborhoods. (1)

Less than a month has passed since the height of Spain’s COVID-19 lockdown policies, which confined children to their homes for more than forty days and elicited fierce warnings from parents, teachers and medical professionals on the potential long-term effects on children’s physical and mental health. The word ‘crisis’, as professors of fin-de-siècle Spain are wont to explain, can be a period of intense difficulty or the point when a patient either succumbs or recovers. As children re-emerge in parks and public spaces, what can historians and linguists learn from these episodes and their reception, distant in time and space?

As pedagogue Heike Freire noted in an interview with ABC in early April 2020, Spanish children had all but ‘disappeared’ from the public sphere. “Ya no pueden ir al colegio, estar en los parques, las plazas… Y el Gobierno ni siquiera los ha mencionado en el Real Decreto que establece el estado de alarma.” Invoking governmental lapses, she argued that children’s welfare must be part of the wider conversation. Public health measures must recognize the child’s unique developmental needs, inextricable from the outdoors: ‘las necesidades de los niños de estar al aire libre, de moverse, de recibir luz natural y juego’. (2)

Spain’s COVID-19 regulations responded to an urgent epidemiological necessity, namely to limit family-to-family contagion during an international pandemic and national emergency. Arguments against the policies’ reach, however, harkened back to century-old campaigns to recognize children as protected members of society. To do anything less, as Freire’s petition warned, risked committing a ‘delito de negligencia y abuso’ against them.

As inscribed in the 1924 Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child, social reformers declared for the first time that children had particular needs and rights. The first among these was ‘the means requisite for its normal development, both materially and spiritually’. (3)

This was a radical declaration. Cities of the early twentieth century faced dire public health crises manifest in high infant mortality and ill health. In the crowded streets of Spanish neighborhoods like Madrid’s Lavapiés, children gathered in narrow, heavily-trafficked streets and dark, stuffy homes and classrooms. Following international research, pedagogues made clear that children needed sunlight (known as heliotherapy), exercise (in varying active forms of play, exploration and calisthenics), a nourishing diet and fresh air.

Local governments were called upon explicitly to intervene: ‘Todos los Ayuntamientos, sin duda alguna, tienen que pensar en la creación de campos de juegos, de bosques y de jardines en armonía con las necesidades de la higiene, de la educación y del esparcimiento de sus respectivos vecinos, pues constituyendo el juego, especialmente en los niños, una necesidad fundamentalmente biológica, no puede explicarse que sean las Ordenanzas municipales las que lo prohiban. Esto no es lógico ni justo,’ argued Madrid bureaucrat Pedro Roy Herreros in a 1928 municipal competition aimed at improving school hygiene. With international researchers showing the critical importance of playgrounds, forests and gardens for children’s development, he suggested, it was shortsighted and downright unjust for local governments to stand in the way of public health reforms.

Building upon past efforts to bring urban children to marine sanatoria or mountainous colonias escolares, undertaken over the past half-century, this was a call to transform schools in simple but radical ways, knocking down walls, building gardens, letting in sunlight and creating playgrounds on disused municipal lands. Like advocates before and after, Roy Herreros relied on examples from pioneering schools in England, France, Germany and elsewhere to set the standard for Spain, while he condemned municipalities that ‘unjustly’ ignored children’s needs. As Freire would later note about COVID-19 policies, countries including France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany all explicitly mentioned children; only Spain failed to reflect the ‘características especiales’ of childhood in its policies.

The resonance of these two movements lies in common cause made by concerned parents, teachers and doctors in pursuit of a holistic pedagogical ideal. Today’s parents and teachers take to Twitter and Change.org, but those of the early twentieth century too fought their battles in the public sphere. Employing a common language of health, growth and vitality, reformers called upon governments to take children’s entire ‘material and spiritual’ needs into account.

Dr Anna Kathryn Kendrick is Clinical Assistant Professor of Literature and Director of Global Awards at NYU Shanghai, and the author of Humanizing Childhood in Early Twentieth-Century Spain(Cambridge: Legenda, 2020)

1) Germán Penedo, ‘La escuela en el campo’, La Correspondencia de España, 8 May 1909, p. 1.

2) Ana I. Martínez, ‘“Los niños necesitan salir a la calle por salud así que tenemos que ser capaces de elaborar otras medidas porque esto se va a prolongar más de un mes”’, ABC, 1 April 2020.

3) Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child of 1924, adopted Sept. 26, 1924, League of Nations O.J. Spec. Supp. 21, at 43 (1924).

‘What are you reading?’ The Old Normal: Return to Eldorado, from Duncan Wheeler

I could tell you about how I’ve just finished re-reading journalist Manuel Chaves Nogales’s reconstruction of bullfighter Juan Belmonte’s autobiography. The literary recreation of the life of the matador from Triana, which ended in suicide in 1962, warrants further discussion but, on reflection, confinement calls out for light relief. So I’ll talk instead about a third-rate soap, which takes me down memory lane to the eve of me first taking up Spanish at school in 1993.

Forget Blur versus Oasis, the real cultural war of the nineties was between Eldorado (BBC, 1992-1993) and Coronation Street (ITV, 1960-). With the imminent threat of having the privilege to charge a licence fee removed if the public broadcaster failed to reach a wider cross-section of society, the BBC was in desperate need of a hit. Ten million pounds of public money was pumped into building a set on the Costa del Sol for a new soap-opera, dreamt up by the creative minds behind EastEnders (BBC, 1985), and featuring an ex-pat community. Working title Little Britain was deemed too parochial in the year of the Maastricht Treaty, and characters from across Europe were shoehorned into rushed scripts written by committee.

For the first time in two decades, I’m back living with my parents. A lifetime soap addict, my mother has requested, only half in jest, that the EastEnders theme tune be played at her funeral. Her concern that I might lose touch with my cultural heritage was such that copies of Inside Soap magazine were dispatched to Madrid during my Year Abroad. There is no graduation picture of me at my family home. In the kitchen, however, there is a framed photo of my long suffering post-doctoral researcher and me in front of the Rovers Return, taken at the Granada ITV Studios last year when I was called as reserve member for the Wadham College alumni team in University Challenge. A collateral benefit of coronavirus has been a final metamorphosis into what cultural theorists define as an omnivore, digesting Geoffrey Parker’s excellent new biography of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor before joining my Mum to revisit Eldorado on YouTube. As with many academic relativists, I’ve been raised to showcase my inner-snob when it comes to eating and drinking (as far as I know, no cultural studies conference has organised its official dinner in a Wetherspoon or Nando’s), but to invoke omnivorous tendencies by relishing in the non-guilty pleasures of mass culture.

The first episode of Eldorado was broadcast during my last days of primary school. It was axed by incoming BBC Controller Alan Yentob some twelve months later. After taking German as a compulsory first language at my Birmingham grammar school, we were offered the choice of Spanish or French as a second language the following year. My decision was based on a preference for Madonna’s ‘La isla bonita’ over Vanessa Paradis’s ‘Joe le taxi’ (to this day, the only phrase in the language of Molière that trips off my tongue) as opposed to anything I saw in Eldorado. Truth be told, beyond the sultry Pilar – an object of desire for her boss, playboy rogue Marcus (or, as she pronounces it, ‘Marcoos’) – Spain is little more than a sunny backdrop populated with an incongruous hotchpotch of donkeys and disparate European nationalities. If the past is a foreign country, revisiting Eldorado in the post “#Me-Too” landscape brings the viewer face-to-face with a disturbing spectacle of times past, when it was seemingly acceptable for a middle aged restauranteur, Bunny, to return from England with Fizz, a seventeen-year old bride he has met when she was sleeping rough. Trish a fifty-something blonde barroom singer is shacked up with teenager Dieter, brought to life by Kai Maurer, a German tourist who had never acted prior to being discovered by the BBC producers selling timeshares on a local beach. He really shouldn’t have given up the day job.

Pier Paolo Pasolini and Mike Leigh have shown what it is possible to achieve with non-professional actors and improvised scripts. But it’s a high risk strategy. Eldorado was a creative and commercial disaster. That said, when the airports reopen, I’m still tempted to embark on a pilgrimage to the fictional town of Los Barcos, located on the outskirts of Fuengirola. The old set has since been repurposed as a three-star hotel. I’ve not confined myself to bed quite as much as Proust in recent weeks, but I’ve no compunction in admitting to binging out on forgotten episodes of Eldorado, Madeleine cakes for the COVID-19 age.

Professor Duncan Wheeler, Chair of Spanish Studies, University of Leeds. Editor (Hispanic Studies), Modern Language Review