Professor Peter Ives (The University of Winnipeg) writes about the event ‘Modern Languages, Global English and the Future of the EU’ held at the IMLR in September 2016

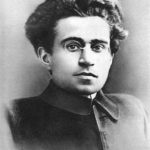

Antonio Gramsci is one of the most influential Italians of the 20th Century. But what could his writings composed in fascist prison cells in the late 1920s and early 1930s have to tell us about multilingualism and global English in this post-Brexit world? This was one of the questions that brought me from Winnipeg, Canada where I teach Political Science to Senate House in London on a beautiful, sunny Wednesday in September of this year for a conference hosted by the Institute of Modern Languages Research (IMLR) and the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory.

There were also other related questions around which Alessandro Carlucci (University of Oxford), Katia Pizzi (IMLR) and Giancarlo Schirru (Università di Cassino e del Lazio Meridionale and the Istituto Gramsci) organised the lively and stimulating conference, “Modern Languages, Global English and the Future of the EU.” Michele Gazzola (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) presented research showing how crucial the EU’s official multilingualism policy is for the democratic enfranchisement of EU citizens. Federico Faloppa (University of Reading) illustrated the obstacles that refugees and immigrants to Italy face despite their often diverse and extensive multilingualism and communicative skills. The day-long conference concluded with a provocative talk by Arturo Tosi (Università degli Studi di Siena and University of London) drawing on an essay by Italo Calvino moving beyond questions of multilingualism as the collection of skills in various languages and towards translation and the relations among and in a diversity of languages.

The papers and extensive discussions emanating from them throughout the day weaved in and out of many topics concerning the politics of language, the impact of the increasing prevalence of English – perceived or real, the role of multilingualism, democracy, inclusion and equality. One thing that most of the participants agreed on was that there is a danger of language policy reinforcing bureaucratic elitism that can alienate ordinary people and further divide and stratify – to use Gramsci’s terminology – differing sectors of the populations of Britain and European countries. This can be as true of the liberal left political forces as it is of the neoliberal right.

There was perhaps less agreement on whether the context of Italy in the late 19th and early 20th century that Gramsci was most concerned about is at all comparable – or contains insights – for the situations we face today. Giancarlo Schirru drew on Gramsci’s analysis of north-south relations and language politics in Italy to argue that if Europe is a linguistic and social community then English is the only candidate to be a truly popular, common language. In a quite different vein, my own paper focused on how Gramsci’s most influential concept, hegemony, has been used extensively by critics of global English to emphasise the ways in which people are forced to consent to learn English or given little choice but to use English if they wish to be successful. I noted that while such critics provide important analyses, if we look more thoroughly at Gramsci’s writings on language we see that he was actually in favour both of a common language for Italy as well as working towards common languages internationally. His criticisms of how Italian was being standardised and propagated focused on the selection of just a single vernacular or dialect, that of the middle-class of Florence, and an attempt to spread it throughout Italy almost as if it were a foreign language. This does not, however, mean he was critical of the eventual goal of a truly popular common language for Italy, nor of government intervention in fostering such a common language. Gramsci emphasised that we need to focus on the specific forms of such common languages – he urged that they be truly popular and also that their propagation should not be premised on the eradication of multilingualism or the decline of vernacular languages or what are often called dialects.

It seems to me that the incredibly important differences between Gramsci’s historical context and ours especially concerning levels of literacy makes such lessons more, not less, important for us. Of course, this does not mean that Gramsci has all the answers for us, not by a long shot. But his approach helps us gain a deeper understanding of key issues. For example, Michele Gazzola criticised the empirical accuracy of many media and scholarly assessments of English proficiency among Europeans. Gramsci’s perspective adds to this important empirical issue the extent to which many Europeans learning English in schools perceive it as a language not related to their lives and experiences or a language being imposed from above.

Of course, such issues are crucially important as the UK withdraws from Europe. English will move from being the main language of British citizens who had been a significant portion of the EU population to a language of the Irish and Maltese but an important lingua franca of many elites in Europe. This may likely exacerbate the linguistic divides between elites and the general citizenship in ways Gramsci warned against. However, it could also open spaces for us to rethink how we understand multilingualism in very concrete situations such as supporting and assessing immigrants and refugees, as Federico Faloppa highlighted. It may also be an opportunity to reconsider the importance of translation as more than a technical operation of professional translators and more as a possible way of thinking about multilingualism, as Arturo Tosi suggested.

The great value that the Institute of Modern Languages Research provides with its support of conferences like this is that it enables us to think through such crucial social issues with scholars and researchers from a host of different disciplines, places and perspectives. The Director of IMLR, Catherine Davies, who opened and attended much of the day’s events, provided essential support for the success of this conference.

Professor Peter Ives (The University of Winnipeg)