Jack Tarlton (actor, director and teacher) talks about the recent workshops held in Argentina, ‘Exploring Theatre Translation‘:

Monday 4th November 2019: A taxi ride through the rain-pelted streets of Buenos Aires. Beside me is Catherine Boyle, Professor of Latin American Cultural Studies at King’s College London and Primary Investigator of the Language Acts and Worldmaking Project. In the front getting the full experience of the wayward traffic is John Donnelly, playwright and screenwriter. The three of us have never worked together before but today, along with Lucila Cordone and María Laura Ramos of the Argentine Association of Translators and Interpreters, we start Exploring Theatre Translation, five days of workshops with a group of student translators. Using three of John’s plays we aim to offer practical guidance on how to approach the often mercurial process of theatre translating, culminating in the group translating a section of his latest play, The Porter, to be performed in a staged reading on Friday night.

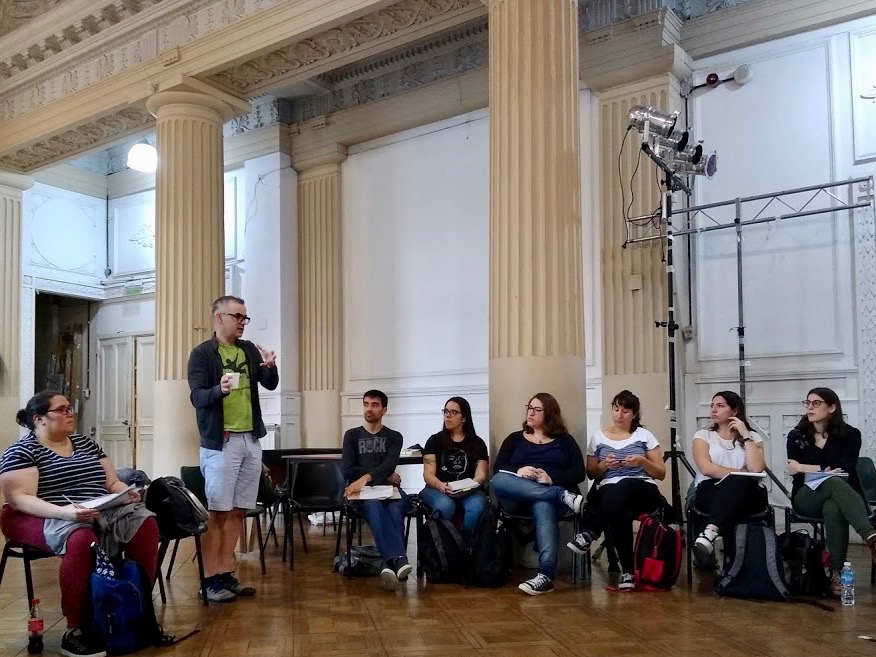

We’re working in Paco Urondo, an arts space that is part of the University of Buenos Aires, which John perfectly describes as “raffishly beautiful” and is the former dining room of what was the city’s first luxury hotel. The room is cavernous and the sound of tango music dancing through a PA system echoes around the space and welcomes us in. We meet Lucila, María Laura and the students and arrange our chairs in a wide circle. Although each of us brings a wealth of practical expertise and we have a well worked out plan for the week we are keen to keep a sense of discovery and improvisation alive, so this does feel like an experiment. And the bulk of the workshop will be carried out in English and we have yet to assess the level of fluency amongst the students. I briefly introduce the team, give a very quick overview of what we hope to achieve and then hand over to John for “The Match Game.”

John starts, striking a match and then attempting to give his life story while it remains lit – “When I was young my friend’s father would take us to football matches where I learnt a lot about storytelling and about how men relate to each other” – before handing the box of matches around the circle. “I am a student of Lucila’s” – “I live outside of Buenos Aires” – “I am scared of fire but actually this isn’t too bad.” – “If I cannot become an actress then I will die.” Instantly, you get a sense of everyone in the room, while watching how they try to keep the flame alight or blow it out is as illuminating as what is actually said. What I hear most is “I am very excited to be here” and although I think initially this is perhaps just filler, I quickly realise that there is a true sense of excitement and anticipation in the room towards the project. It’s good to learn too that people are coming to the workshop from widely different backgrounds; some have experience of working on the stage while others have never translated drama before. And to discover that their proficiency in English seems very high.

We start by looking at the first few pages of The Knowledge, a play of John’s that was first performed at the Bush Theatre in 2011. We deliberately have not given it to the group beforehand so the first read is a collective rush, as we each take it in turn to read one line of dialogue going round in the circle, and meet a group of unruly secondary school pupils trying to undermine their new teacher. Challenges are thrown up straight away. How would you translate the very first line – “Top Shop?” What action has preceded the start of the play? What is the equivalent in Spanish of an English character using the Spanish word “Nada”? The group is divided into pairs to locate these challenges and to attempt a very rough first draft of the scene in Argentine Spanish.

When it’s time to report back we quickly realise that most became mired in the first page or so. The specific references to the South East of England have prompted lots of conversations about where to locate the play. With Catherine encouraging them to set aside these worries for now we then give them a longer passage to work on which results in a far greater fluidity and the translated passages are shared by the end of the afternoon. Students in groups of five gamely hunker around a laptop to read and bring the scene to life. We finish by asking the students how they would translate the title The Knowledge, with its multitude of meanings into Spanish.

By now the rain has abated leaving a bright but still muggy afternoon, through which we walk to Lenguas Vivas, where Lucila and María Laura teach, for a reading of part of John’s version of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull and a Q&A. I auditioned for the original production by Headlong in 2013 so I am extremely happy to finally play Konstantin to John’s Petr, with the other parts read by Catherine and two of the students. In the Q&A that follows John speaks of his belief that Chekhov’s original does not exist as it once did; that the passage of time and its elevation to classic status has blunted the force that it once had, of his desire to make the audience experience it anew from the famous first line onwards, and how he took the play apart and tried reordering scenes only to reassemble it in Chekhov’s design. There is an open, relaxed feeling to the event. Students whisper our questions and answers to their tutor in Spanish to be assessed and others who are walking by are drawn into the room to join us. Behind us the last of the rain clouds are burnished orange and deep grey as the sun begins to set on our first day.

Tuesday 5th November: Bright sunshine this morning and which will last all week. After Catherine leads us through a series of bilingual tongue twisters we settle down with The Pass, which explores a footballer struggling to deal with fame and his sexuality. First performed at the Royal Court in 2014, it was released as a feature film in 2016.

We gave the play to the students last week so that they were fully aware of the whole story. Over the course of the play’s three acts it is revealed that what one character is doing to another is very different to what it originally appeared to be and we felt it was fundamental for the translators to grasp this. We read a section of the first scene and then ask for comments. In an attempt to not get caught up in an over-complicated discussion we encourage each student to simply start with “I noticed that …” or ask us a simple question such as “What is … Portsmouth?” This provides short, insightful points upon which to start a dialogue and we adopt it as a working model for the rest of the week, locating and unpicking the specific challenges for each script.

With a far greater understanding gleaned of the first scene I then turn their attention to a later scene to encourage them to attune their thinking to how an actor would approach the play. Together we work out the objective of each character; what they want from the other, the obstacle that is stopping them from achieving this and the actions that they perform to get around it. As a writer John will do this with his own text and I feel it is important for the translators to find that perspective also, to dig into the play and not to look down on it purely objectively. I set them the task of writing an action for each line to show what the character is doing to the other with it, but having thought that I had explained the concept clearly when they present their work almost all of them misunderstood the brief. This proves an extremely important lesson for us. We have to remember that this work is tricky and we are trying to teach it in a language that is not the students’ original and so to strive always for clarity. Upon giving my own thoughts on what the actions are however they all seize the concept and we finish the afternoon with everyone successfully translating these two sections of the play and performing them for the rest of the group. There is a real feeling of achievement from all as they share their completed work. Another quick-fire round of how they would translate the title of the play and we are done before all head to the theatre for the evening.

Wednesday 6th November: This morning it is my turn to lead the morning game and soon everyone is miming, shouting and running back and forth with “Lemonade”, a game that I was introduced to at youth theatre and have never tired of sharing. Properly warmed-up we then turn our attention to The Porter.

It is a taut, unsettling play about class, sex, shifting loyalties and how much we can believe the past. It is a play with sweaty palms. The students were sent it some weeks ago and respond brilliantly to it on our first read together, discovering that the first dramatic arc concludes at approximately thirty-five minutes in. This will be what we present on Friday evening then, which will be very first time the play has been performed in public. John divides this into seven sections and the group into pairs to work on a section each. We have learnt that two people work best together, enabling each translator to use the other as a sounding board and their combined energy to drive them forwards. After some time with their pieces we come together for questions and “I Noticed That…” which prompts the drawing of a detailed league table of British supermarket chains, music festivals and types of tea. It starts to come into focus that this play is set in “this imagined England” of John’s, a landscape created though his own perception of nationhood and class and now to be engendered anew through an Argentine perspective.

Each pair is then given the rest of the morning and into the afternoon to produce a rough first draft. Each have their own specific challenges, from dealing with seemingly out of character vocabulary, to the sexual subtext of everyday interactions, to translating a passage of 17th Century metaphysical poetry. Our guiding note to them all is to think about what the characters are doing to the others with each line, that “the force of the utterance” – as David Bellos puts it in his book Is That a Fish in Your Ear? – is far more important than the literal sense. Above all, John encourages them to be bold, to take ownership of the text, it is becoming theirs now.

In the mid-afternoon we gather to read it. And already there exists a new play. A bit rough and with the joins showing, but it has a momentum and a playfulness that speaks to us all, even to John and I with our limited grasp of Spanish. It is hugely inspiring to see how after only three days this group who are still getting to know each other have created something so strong and supple and which will be given to the directors and actors to start work on tomorrow morning.

Thursday 7th November: John has already spoken about the process of writing and staging a play as being one of release. As a playwright you write a play, which is then given to the director, who gives it the actors, who finally give it to the audience. Here though, the play was given to the translators first and this morning it is their turn to release it to Nicholas Lisoni, the director of Paco Urondo who will lead the actors Annalia Malvido, Horacio Vera and Ezequiel Lozano in an initial table-read before handing it over in turn to his long-time collaborator Andrés Binetti who will direct the staged reading tomorrow night. This is the first time that the translators will discover how actors coming to it purely as a piece of dramatic text without being part of its creation will respond. We feel it is important for the translators to sit in on the all sections being read, to learn the discipline needed to be a translator in the rehearsal room, and so after Nicholas leads us all in our morning warm-up, everyone gathers for the first read-through.

As the actors work through the play I feel the thrill of a different kind of release. I would normally worry if the more I worked on something the less I understood it, but here I find it exciting that something that had been so familiar to me just yesterday now already exists in Argentine Spanish, with its own shape and inner structure, the details of which I will never fully grasp. There are still surprising moments of recognition though when a line lands in Spanish and I instinctively know what it was in English. What a fantastic way to start to learn a new language.

After the reading the actors have many questions for the students, most of which are about punctuation and the uncharacteristic vocabulary that they felt was inconsistent. This turns into a passionate debate with everyone involved before Catherine has to remind the group only to comment on their own section.

Everyone is buoyed by the first read-through, especially when Nicholas half-jokingly asks if the rights are available. An early lunch and then the students have the bulk of the afternoon to rework their sections based on the feedback they have received. Warned against too much tinkering by Catherine who reassures them that the work is already very strong, most of the reworking involves finding greater clarity. We reconvene and the play is read once more by three of the group and then a final opportunity to redraft before tomorrow morning.

This evening tickets have been arranged for us all to see Minefield, an extraordinary play directed by Lola Arias and performed by eight veterans of the Falkland / Malvinas Islands conflict. Thrilling, moving, funny, angry and compassionate it is one of the finest pieces of theatre I have seen for a very long time and I am so glad that I can experience it as part of a predominantly Argentine audience.

Friday 8th November: A staged reading can mean many things. Often it involves actors simply reading from their chairs but Andrés Binetti shows the same dynamism in approaching the play as he does in the highly physical warm-up game that he starts the day with and that definitely needs no translation. Although they still have their scripts in their hands the actors fully embrace the text, combining a beautiful naturalism with a heightened, abstracted staging. An impromptu performance space is erected using six chairs, stage directions and sound effects are spoken and scraped through a microphone, the characters intimidate one another by hovering over each other, or seduce each other by sitting a certain way in a chair. Simple lines are mined for nuance, while a longer passage that originally elicited laughter from the group is played with a solemnity that while possibly was not what was intended is fascinating to see transformed in that way. I can only imagine how empowering it must be for the students to see their work being treated with the same robust respect that any professional script would be. Also, the physicalisation reveals real differences in British and Argentine behaviour. While every morning here starts with a kiss Hello, does the moment when a husband makes a show of kissing his wife on the cheek carry the same weight?

Working through what we would normally call lunch, time is called on the rehearsals in mid afternoon so that the actors can rest before the evening show. We spend the remaining time sharing our observations of the rehearsal process, using our now familiar prompt of “I Noticed That …” Catherine then shares her experience of being a translator in numerous rehearsals, encouraging all the students to stand up for their work and to find their own agency within the company.

We then break for the chance of some late afternoon sun for those who want it, while I arrange the chairs for the audience as the lighting is rigged for tonight’s performance.

When it comes it is magical. Ezequiel, Horacio and Annalia perform with vitality and real emotional investment. The process of release is completed as the audience takes this play as their own, staged by the actors and director in a day, and translated in two days by a group who only came together at the beginning of the week.

Afterwards a photograph is taken of us all and I am suddenly made aware of how many people were involved in creating the piece tonight and that although it was the culmination of the week, it was probably not the most important part. I believe that what was more important was the process itself. Three people from Britain and two from Argentina discovering how best to impart their knowledge and to draw the best out of each other and how we in turn could learn from the students. It was they who provided the real engine of the work. They responded brilliantly to our proposals and deadlines, producing multiple scenes from The Knowledge and The Pass, learning from John’s own experience of adapting The Seagull and then melding their separate scenes into one cohesive whole for The Porter. Over five days there truly was an exchange of ideas as we discovered how best to translate the human experience from one culture to another.

Our time together exceeded all my expectations. So now, the work begins to bring an Argentine playwright and actor to a group of students in Britain. I can’t wait to get started.

Jack Tarlton is an actor, director and teacher. His stage work includes lead roles at the National Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company, Young Vic, Royal Exchange Manchester, Sheffield Crucible and in the West End. His screen work includes “8 Days: To the Moon and Back”, “The Imitation Game” and “Doctor Who”. He has directed numerous staged readings of international work and has taught Shakespeare and modern drama studies and adaptation of prose for the stage at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, Oxford University, East 15 Acting School and for The Old Vic and Out of Joint and was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Modern Languages Research at the University of London.

Generously supported by the AHRC, OWRI Cross-Language Dynamics, and Language Acts and Worldmaking, AATI, and Instituto de Artes del Espectáculo and Centro Cultural Paco Urondo (Universidad de Buenos Aires)