Clare George introduces the Laterndl, providing the background behind the Making Theatre in Exile project

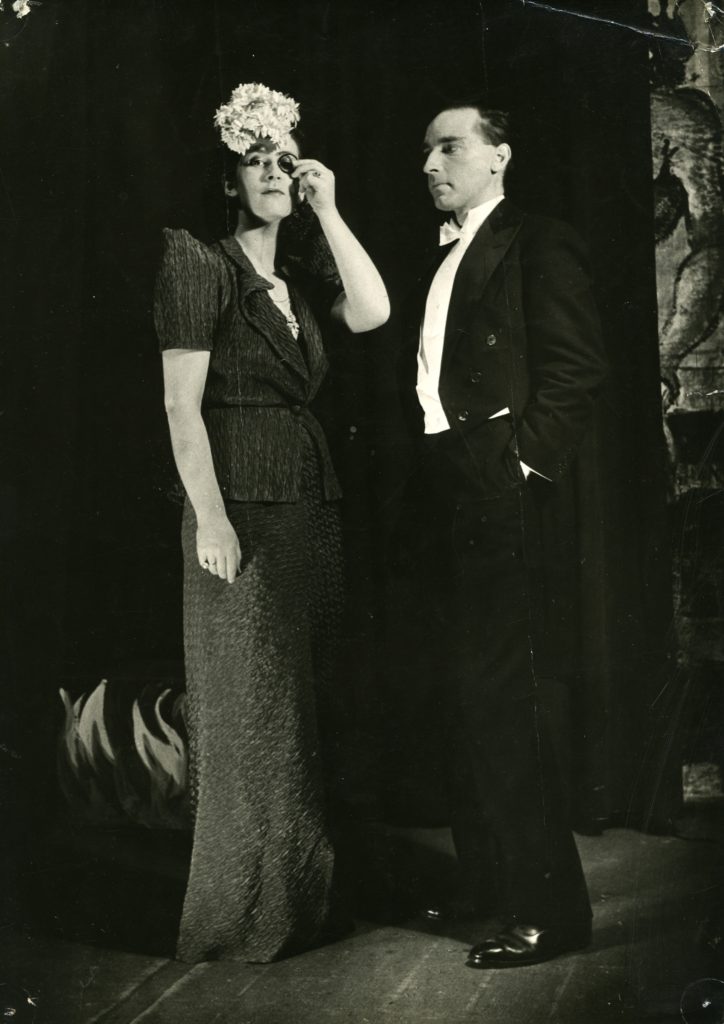

Eighty years after it first opened in Hampstead in November 1939, the story of the Second World War Austrian exile theatre, the Laterndl, was brought to life by the international theatre group Foreign Affairs as part of the 2019 Being Human Festival. The ‘Making Theatre in Exile’ (MTIE) project saw performers delve into the archive of its director Martin Miller and weave together extracts from letters, scripts and newspaper reviews to create a 1930s’ Viennese cabaret-style evening of sketches and songs with accompanying music arranged and performed by pianist Malcolm Miller.

The Laterndl was founded in June 1939 by members of the Communist-inspired refugee support organisation, the Austrian Centre. The idea was to establish a theatre that would ‘keep alive the light of Austrian culture’ at a time when Austria had politically ceased to exist. It was to be modelled on the Kleinkunstbühne or small arts theatres of mid-1930s’ Vienna, where many of the Laterndl actors and writers had produced political cabaret before fleeing Austria. These semi-underground stages had provided one of the few remaining public spaces in which criticism of the regime and the growing influence of Nazi Germany could still be expressed during the Austrofascist period of 1934-1938. Apart from two breaks, enforced by the compulsory closure of all theatres at the start of the war and the internment of many of the actors as enemy aliens in May 1940, the Laterndl performed regularly for the following six years. The theatre provided a platform for an array of new works telling stories from the refugees’ world and attracted nearly 10,000 visitors within the first seven months alone. It raised British awareness of Nazi atrocities, support for the war against Hitler, and brought a beacon of hope to the 30,000-strong traumatised community of Austrian refugees.

Despite these achievements, like many other refugee groups in history, the Laterndl left relatively few archival traces of its activities. Its existence is noted in the state records at The National Archives, but only in the context of the potential dangers posed to the nation by its members gaining UK citizenship after the war. As archives theorist Andrew Prescott notes, the experience of exile generally appears in the official archives as ‘an anomaly, with fleeting and transitory individuals and groups seeking help or posing problems’, so to find the refugees’ own stories we must look outside the scope of public records. Sadly, no central records store was recovered when the Laterndl ceased its activities in 1945, so we are reliant on those records which survived the selection and omission processes of individual actors. This is a subjective and arbitrary matter even for fixed groups in settled times, but still more so for those living with the hardships and uncertainty of refugee life in wartime London, for whom record-keeping would hardly have been a priority.

Given this context, the fact that two of the theatre’s main figures managed to salvage and preserve a significant number of records of the Laterndl’s activities over many decades is a cause for some celebration. Hannah Norbert-Miller (then Hanne Norbert) and Martin Miller, who was to become her husband, were key figures and involved in many different aspects of the theatre’s productions for the first three years of the Laterndl’s existence at least. In addition to Miller’s directing, both were lead actors, and Norbert-Miller also played the role of English-language compère. Their records, whilst not covering all the productions, nevertheless represent probably the most complete archive of the theatre in existence and offer an unparalleled insight into the refugee actors’ world. Researchers in the IMLR’s Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies have used the Laterndl programmes to show how, as in Vienna, each production consisted of short dramatic sketches and songs, often of a topical and satirical nature. The fragments of English-language compère scripts reveal how the actors appealed to non-German speaking supporters like Sybil Thorndyke, H.G. Wells and J.B. Priestley. Letters from writers and other figures close to the theatre point to the deliberations and heated political discussions which must have taken place amongst the artistic team but which often went unrecorded. Newspaper clippings from both the British and exile press show the enthusiasm with which both German and English reviewers greeted the opening of the Laterndl, as well as the differing views on its role as the war progressed.

The MTIE project aimed to showcase the value of the Millers’ archive for opening a window into this little-known aspect of Second World War history. The performance incorporated letters, memoirs and compère scripts to evoke the moving Laterndl performances which kept alive the work of Jura Soyfer, a cabaret writer whose scripts were smuggled out of Austria by his girlfriend, Helli Ultmann, after his death in Buchenwald Concentration Camp in January 1939. Another bundle of letters revealed how Martin Miller’s Hitler speech parody, first performed at the Laterndl, achieved international acclaim after its broadcast by the BBC German Service on 1 April 1939. It would be the first of many satires by German-speaking writers used by the Corporation as part of its anti-Nazi propaganda campaign. Selected sketches by the theatre’s in-house writers were woven into the performance, some performed for the first time since the 1940s, including a song based on the sole surviving record of the Laterndl’s very own ‘Schwejk’ production composed by the theatre’s musical director, Georg Knepler, and harmonised for this production by pianist Malcolm Miller.

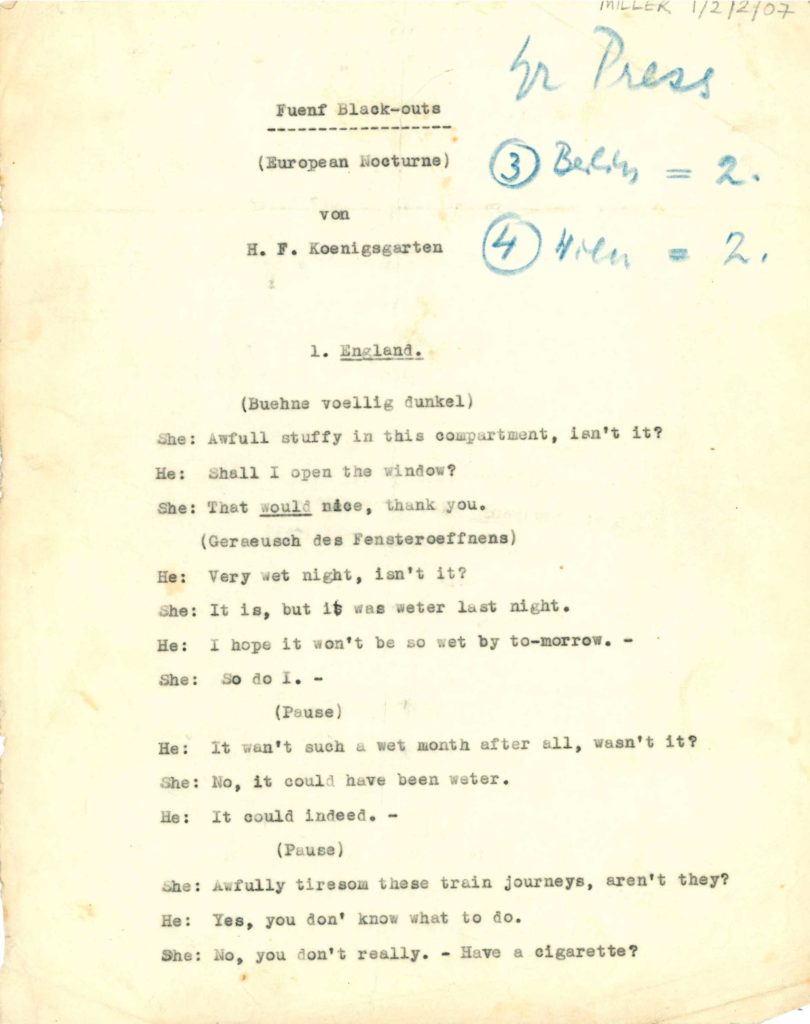

For all the stories of the Laterndl captured in the archive, many more were not – either because the records were lost along the way, or because they were never captured in the first place. Whilst spotlighting those traces of the refugee actors that have survived, the project also aimed to acknowledge the gaps in our knowledge: the issues, problems and questions that they faced and which we will never know about as they are unrecorded. MTIE opened with the discovery of a battered old suitcase containing a jumble of fragile, yellowing papers, some just scraps, to which the actors repeatedly returned – sometimes finding new and illuminating stories, but sometimes searching in vain for a particular record. One such sketch, ‘Five Black-outs’, ended abruptly at the third Blackout scene because the rest of the script was missing; rather than covering up the gaps with a new and fictionalised ending, the performers jolted to a stop. In this way, the performance aimed to expose the notion that the records present us with a complete and knowable account of the refugee theatre’s history as an illusion.

Acknowledging the gaps in the archive and our knowledge of the past of course enhances rather than diminishes the value of the archival material which has survived. As the MTIE project hoped to highlight, those rare glimpses into a little-known past afforded to us by the Millers’ records give us great reason to be thankful for their survival.

Dr Clare George, Miller Archivist (Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies)

The Making Theatre in Exile project was generously sponsored by the Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust (University of London) the Austrian Cultural Forum London, the Being Human Festival, and the AHRC-funded Open World Research Initiative (OWRI)