Clare George introduces the Making Theatre in Exile project:

The ‘Making Theatre in Exile’ (MTIE) project, which culminated in a specially produced performance piece for the ‘Being Human’ Festival at the Hampstead Jazz Club on 14 November 2019, grew out of an attempt to revive the scripts in the Miller Archive of the Laterndl, an Austrian exile theatre from the Second World War. Since that time the scripts had been stored away in boxes, consulted and analysed by academic researchers, but unused by actors and unseen by theatre audiences for whom they were written. Would the stories written by and about a group of German-speaking refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe for the Laterndl theatre still have relevance 80 years later, or would the change in performative context be so great that they would have little meaning for today’s audiences?

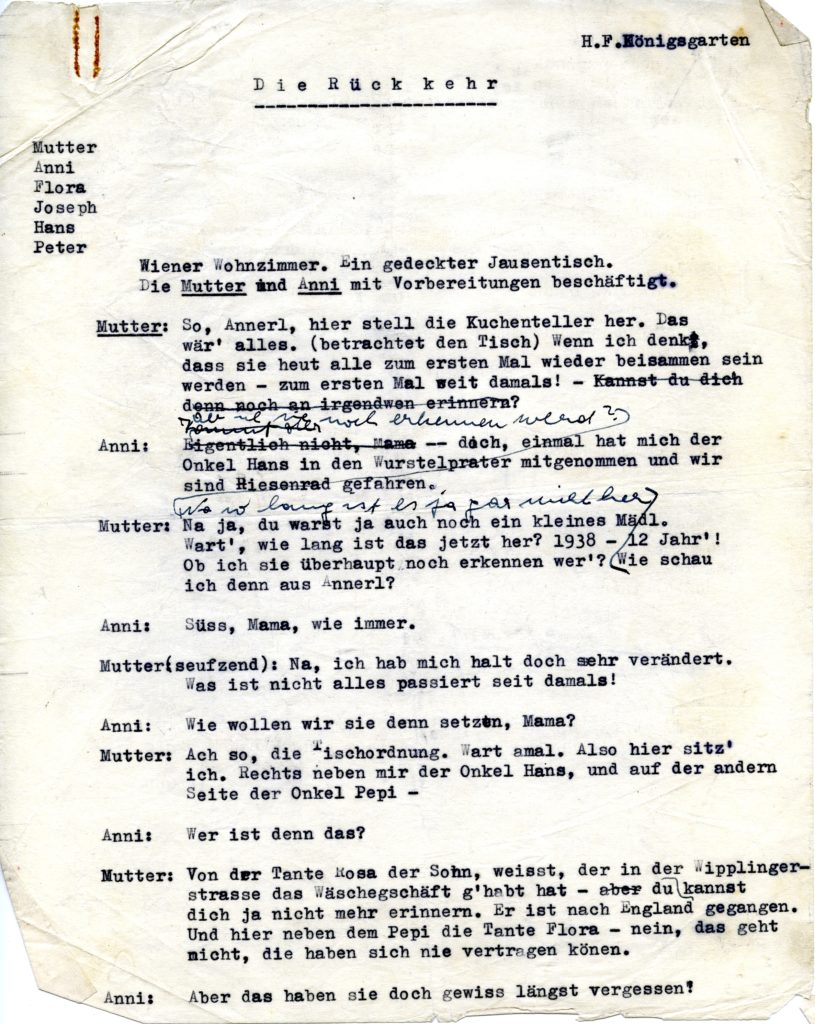

A possible obstacle to the successful engagement of audiences in the UK with the scripts was their translatability. The Laterndl had attempted to appeal to British visitors, marketing its productions in both English and German, but its primary audience was the Austrian refugee community and performances were predominantly in German. In order to increase local community awareness of the theatre the project would need to find a way to make the sketches accessible to non-German speakers. As in the original, a compère would introduce each sketch in English, and English translations of some of the shorter scripts would be provided in the programme. However, some of the longer scripts, like Hugo F. Königsgarten’s comedy ‘Die Rückkehr’ (‘The Return’) for example, presented more of a challenge.

Set in 1950, ‘Die Rückkehr’ sees members of a Jewish family reunited in Vienna for the first time since the end of the war, most of whom have spent the past 13 years scattered across the world in exile and who now plan to settle back in Austria. The sketch anticipates the increasingly transnational identities of those who spent years in exile, and who bring back to Austria the language and customs acquired in the countries where they found refuge. The sketch pokes particular fun at the British through the UK-based refugee Onkel Hans, who plans to establish a café in Vienna to introduce the Austrians to the delights of British cuisine like ‘beans on toast, spaghetti on toast’. Such humour clearly appealed hugely to the local refugee community and may have provided an outlet for the frustration of those who found Britain an alien and often unwelcoming environment.

Because much of its humour is based on the multilingual (in)competence of those who have been in exile, translating the sketch directly into English would have lost much of its meaning. Onkel Hans describes the weather and his journey in a comical mix of German and English littered with ‘false friends’ and mistranslations: for instance, ‘a stormy crossing’ became ‘eine stürmische Kreuzung’.(1) These probably worked with the increasingly bilingual Laterndl audiences, but for non-German speakers amongst the MTIE audience, they would have little meaning. Re-animating scripts like these required bilingual performers like those from the international theatre company Foreign Affairs, specialists in theatre in translation. They followed Königsgarten’s German and English script and retained the original humour, but their performance also added new layers of meaning through the linguistic and performative versatility of the actors. In ‘Die Rückkehr’ the three actors covered seven characters and switched from German to French, British English, American English and Cuban Spanish in rapid succession, making it an entertaining scene even for those with little German.

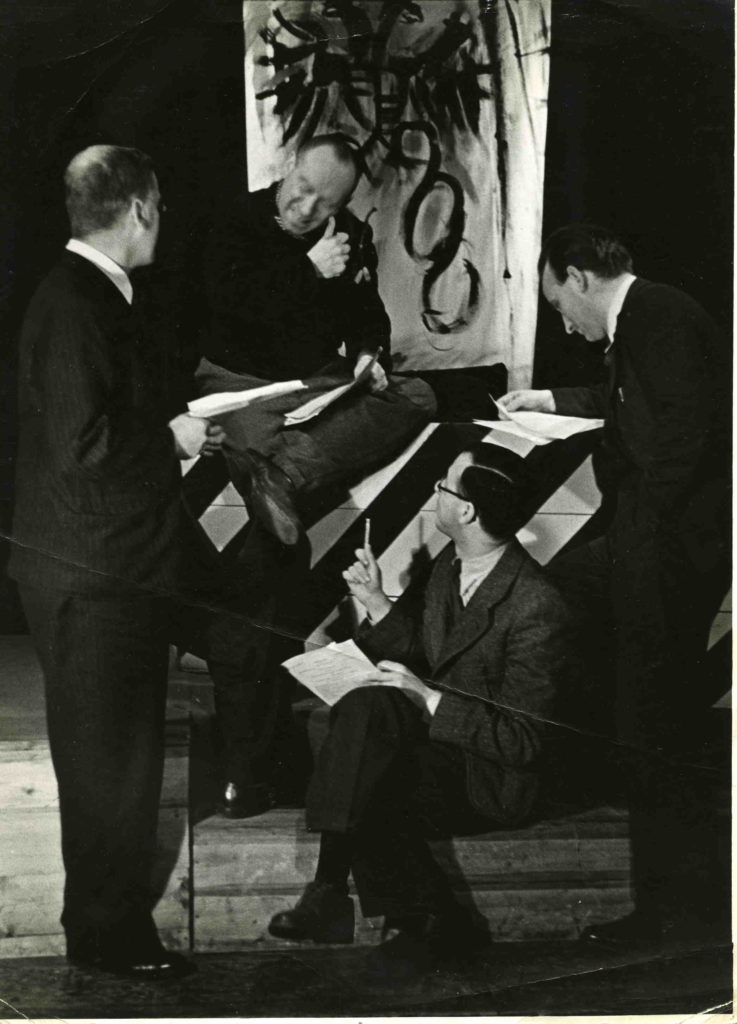

A work-in-progress performance of ‘Die Rückkehr’ and other Laterndl sketches was staged in April 2019, following which a more ambitious plan was conceived by Foreign Affairs director Trine Garrett and Miller Archivist Clare George. Rather than presenting the sketches as discrete items, the production would weave them together with extracts from letters, reviews and other records in the archive to create a new production about the Laterndl and the archive. In the opening scene the actors would ‘discover’ the Millers’ papers in an old suitcase, a performance device which would then frame the individual scenes, with the actors transitioning between their roles as ‘discoverers’ of the records and the figures whose voices are captured in them. Adding this historical context would make the sketches more meaningful to today’s audiences, and emphasising the discovery of the sources of the stories would provide scope to explore the idea of ‘discovering’ the past through the provisional piecing together of information from fragmented archival traces.

‘Die Rückkehr’ provides an interesting example of how this was achieved. A clash of voices from newspaper reviews retrieved from the suitcase reflected the mixed reviews that the sketch received from the exile community. It was in fact one of several that sparked a fierce debate in 1941 over the role of the exile theatre and whether it should promote political engagement or simply entertain. Whilst one reviewer praised the sketch for its great comic value, another, in the Austrian Centre’s Zeitspiegel, advised sternly that rather than making jokes about the return to Austria, the theatre should show ‘wie es wirklich aussehen wird, damit wir alle besser für ihre Verwirklichung kämpfen können’.

A series of letters from Königsgarten to Miller, one of them referring to a now missing alternative script for ‘Die Rueckkehr’, provided an opportunity to highlight the instability of the ‘realities’ of the past constructed from archival records. In one letter, dated early August 1941, Königsgarten proposes that the Laterndl stage a comedy featuring the exiles back in post-war Vienna; he was sure of its success as ‘eine richtige Lachszene’ and the script was already written. By the time the production opened the following month he was having second thoughts, however, particularly about the ending. A second letter reveals that he now wanted ‘Die Rückkehr’ to deliver a stronger, more serious message about the possibility of continuity between past and present and to show, he implied, that returning exiles could pick up where they left off and that the family could become ‘Austrian’ again. He enclosed a new ending for the sketch, which he asked Miller to use instead; it would, he wrote, introduce a grandfather figure who would represent the possibility of ‘die Rückverwandlung der Familie in eine österreichische’.

It was decided that for the MTIE project the second letter would be ‘discovered’ and retrieved from the suitcase only after the sketch had been performed. Without knowledge of the second ending, the audience would assume the sketch they were watching was a re-performance of the original from 1941. Only after the sketch, with the reading of the second letter, would the information about a new ending be revealed, which would call into question the status of the script in the archive and thus also the (re-?)performance. Such uncertainty underlines the challenges that researchers face when trying to uncover the realities of the past from archives, whose meaning shifts according to contextual information that may or may not have survived.

Königsgarten’s intention of showing the possibility of Jewish exiles returning home and families seamlessly becoming ‘Austrian’ again may appear rather innocent to audiences today, given the events that took place in Austria between the performance in 1941 and its setting in 1950. Königsgarten was presumably hoping to offer some comfort to the community despite any knowledge that he may have had about what was happening in Austria. There is no record of whether Königsgarten’s second script was actually used by Miller, but the MTIE performance attempted to underline the shift in historical perspective since the sketch was first performed by subverting the notion of the grandfather representing continuity. Without him, the actors interject, there is no one to transform the family back into being ‘Austrian’ again. The very absence of this symbolic figure signals the impossibility of the continuity that Königsgarten had optimistically imagined.

The ‘Making Theatre in Exile’ project was an attempt to bring back to life the records of a refugee theatre which helped bring together a community living in fear and uncertainty in London 80 years ago. Those records, so carefully retained and preserved over decades by the Millers, inspired a new multi-layered performance which retold their stories in ways which reflected the shifting meanings of the archival records but also tried to make them meaningful and relevant to today’s audiences.

Dr Clare George, Miller Archivist (Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies)

The Making Theatre in Exile project was generously sponsored by the Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust (University of London) the Austrian Cultural Forum London, the Being Human Festival, and the AHRC-funded Open World Research Initiative (OWRI)

(1) A ‘stormy crossing’ is a ‘stürmische Überfahrt’ in German; a ‘stürmische Kreuzung’ is a ‘stormy crossroads’ in English.