Sarah Colvin introduces her new book on Germany from the inside

It will be one of the hardest days in your life, and you’ll never, ever forget those prison gates closing behind you.[i]

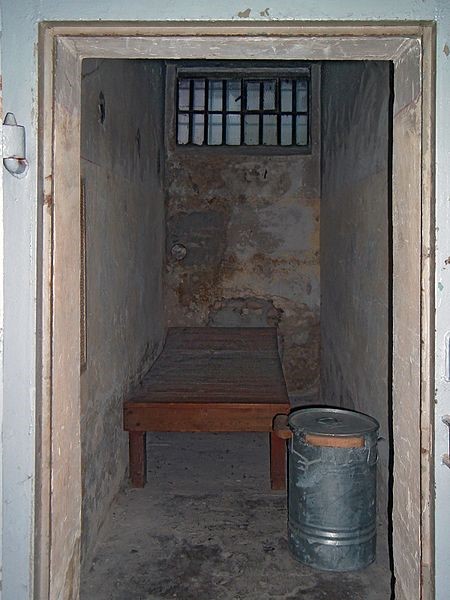

I get out of the bus and see grey walls, barbed wire, doors made of steel. They take us to a cell and our names are called. It’s a while before they call me. I feel terrible, and the lump in my throat just gets bigger and bigger. Then it’s my turn. … I have to get undressed and my clothes get searched again. I have to bend over and pull my arse cheeks apart. I have to lift my testicles. I have to pull my toes apart … The number of my cell is 172, my prison number is 357/9. The officer just unlocks and does the checklist with me; nothing is broken and everything is there. Then he locks the door behind me. My first moment alone in a cell.[ii]

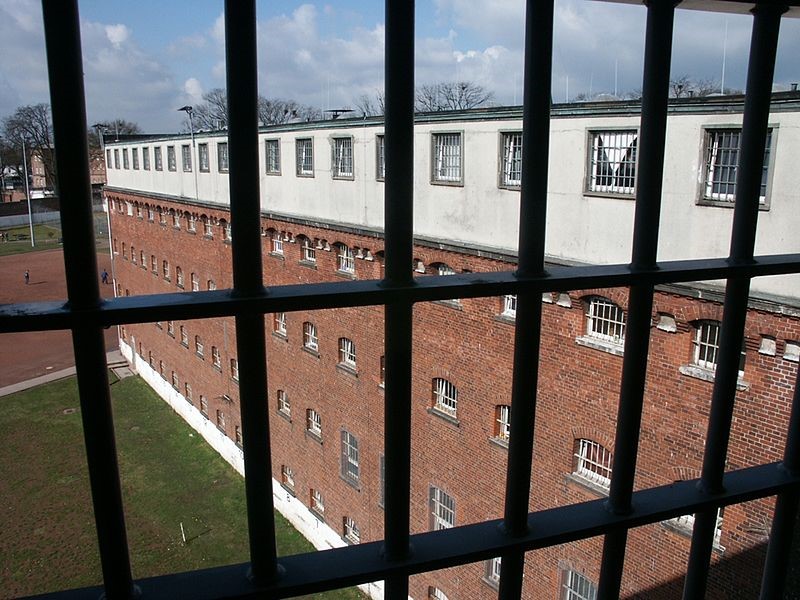

The world’s prison population is growing faster than its general population, and prisons are full to bursting. In overcrowded and understaffed conditions violence levels are high. Detention is hugely expensive while its efficacy is very much in doubt – “people just learn to be better criminals in here” wrote Oliver from a German prison in 2016. In 2019 Germany’s prisons were 88 percent full, with severe overcrowding reported in some.

It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.

(Nelson Mandela)

Shadowland tells the story of Germany after 1945 in the words of its prisoners. That is a different and often shocking perspective on the nation – but it’s worth bearing in mind that Germany locks up fewer people, in generally better conditions and with better human rights, than the UK or US. At 140 per 100,000 the incarceration rate in England and Wales is approaching double Germany’s rate of 78 per 100,000; the US tops the world charts with 655 per 100,000. German nationals in prison have the right to vote, unlike prisoners in the US or UK. Recently a prisoner union (Gefangenengewerkschaft) was founded in a Berlin prison, focused on issues like pay and pensions. Germany offers better provision for families and for women with children, and there is a glimmering awareness of the needs of transgender people.

CC-BY-SA

The story begins in 1945, in a country on the edge of social and legal collapse. Orphaned and abandoned children slept in the woods, stealing and scavenging, often laying the foundations for a “criminal career”. In the eastern zone hundreds of thousands froze, starved or died in Soviet Special Camps, or were deported for hard labour to the USSR. The GDR created interrogation centres for its secret police, the Stasi, and torture facilities including the notorious water cells and standing cells. Outside, in what some called the “big prison” of the walled-in nation, most people preferred not to know what was going on. Meanwhile in West Germany denazification was a challenge (“the prison guards were old Nazis,” one man reported – “a real truncheon brigade”), and a long-awaited grand prison reform erected, in the words of a prisoner, “little asbestos walls in Hell”.[iii]

Prison is a microcosm, a reflection of life outside.

(Peter Zingler, scriptwriter and former prisoner, 2016)

Over and again, stories from the inside say that prison is society’s mirror, and society needs to take a long, hard look at itself. In the 1960s a West German prisoner wrote a letter to the state prosecutor describing the case of X, a young offender who grew up in care homes and borstals and “continued his education” in prison. The courts declared X asocial and a psychopath. Not only the justice system, the letter points out, but every single person who had contact with the boy in an official capacity since he was fourteen years old must, therefore, have “failed disgracefully” – “don’t anyone tell me that it was all the boy’s fault.” Another writer makes the same point. “Yes, we’re abandoned, we’re excluded from human society. But do we really bear the entire burden of guilt?” “When you look at us it’s like you’re looking into a mirror of your society”, a man serving life told journalists who interviewed him. “Dear God, where do you think we come from? We’re not from the moon, we come straight out of your damn society and everything we carry with us in here we learned out there”.[iv]

Mirrors don’t always show things it’s comfortable to see. The gentle “Ostalgia” some feel for the East German past isn’t shared by anyone who spent time in an East German prison. Going to prison in West Germany was no walk in the park, but the exacerbated hiddenness of penal practices in the East, and the authoritarian bent of the state, made for peculiarly cruel and arbitrary conditions. Those who experienced them write of being “hung up” on cell bars or chained to the floor, or of prisoners left standing in their own urine or faeces in a flooded water cell. Prison in the GDR meant being denied access to the criminal or penal codes of the state that had incarcerated you, and permanent unclarity about what the future held. You might be released; equally you might find yourself in long-term solitary without a reason given. Erich Loest was held for 7½ years in East Germany’s notorious Bautzen II, 2½ of them in gruelling solitary, without ever being told which paragraph he had been convicted under. The Black East German writer, André Baganz, spent 5 years in solitary confinement. When he asked why his captors told him they did not need a reason.

I swore to myself that one day I would write down everything I was experiencing and publish it.

(Birgit Schlicke, on imprisonment in the GDR in 1988)

In 1990, German unification offered the opportunity for a new start. “The future’s in the air – I can feel it everywhere, blowing with the wind of change” sang The Scorpions. But how strongly did the wind of change blow on the inside? “It can’t be true that there are prison conditions like this in Germany”, wrote Katharina from a German prison in 2010, observing rats and broken windows in midwinter. She hated using the lavatory “because everyone had a perfect view of it from their bed.” A national report in 2017 complained that many shared cells still had no wall or partition dividing the washing facilities and WC from the main living space. “This kind of imprisonment ought to be a thing of the past”, wrote Martin Finke, after drinking his own urine in a punishment cell when his pleas for water were ignored.[v]

One woman was crying. They told her to stop or they would put her in the bunker. She was next to me in my cell. She didn’t stop crying and two officers came with a bucket of ice-cold water. They poured it over her and then put her in the bunker.

(Rita, FRG 2018)

Numerous present-day stories describe sometimes fatal instances of violence and medical neglect: “surviving your time in prison is a constant fear and worry”.[vi] And still, the cultural mainstream struggles to hear stories from the prison. Prisoners suffer from what Miranda Fricker calls a credibility deficit – as a radically marginalized group of people who often come to prison from already-marginalized communities, prisoners find that their stories are at best inaudible to those outside, at worst dismissed and disbelieved.

The people out there, on the other side of the wall, never believe a word we say.

(Peter Jörnschmidt, FRG 1972)

And still, for people in prison, one way of surviving incarceration is to write. “Writing can take you to freedom,” declared Peter Feraru – “the opportunity writing offers to change something, both in yourself and in your environment, is huge.”[vii] It would be sentimental to claim that a prisoner’s-eye view is more authentic or true than other perspectives. But it is probably not less true. In a cultural context where some of the most prominent figures in society are daily exposed as shameless liars, the status of narratives from prisons is changing. H. Bruce Franklin, a professor of American literature, noticed with a little surprise in 2008 that the Heath anthology of American literature now included a section called “Prison Literature”. In the same year the Publications of the Modern Language Association of America made incarceration the topic of its May issue, and Texas Studies in Literature and Language produced a special issue on “Cultures of Detention” for the Fall. In 2015, the American Book Review issued a number on prison writing.

“Communicating your experience is resistance to a power that is taking away your subject status”, wrote Karin Amann, a former writer in prison and now a jury member for the Ingeborg Drewitz Prize, Germany’s most significant literary prize for prisoners. “All the pressure that built up inside me was released via my pen”. “I can trash the cell when I’m desperate,” explained Karlheinz Barwasser, “or I can give the screw or another prisoner a smack in the mouth. But all those explosions come from the same place as my explosions on paper”.[viii] Thomas Galli, a former prison governor and a patron of the Drewitz Prize, sees writing as the opposite of violence. “Anyone who hurts others or causes severe damage is dividing people, creating fissures, digging trenches, causing injury,” Galli writes. “Anyone who punishes another human being by incarcerating them is dividing people, creating fissures, digging trenches, causing injury”, he goes on. “Literature, by contrast, brings us together”.[ix]

Sarah Colvin, Schröder Professor of German and Fellow of Jesus College, University of Cambridge

[i] Dirk Glebe, Handbuch Knast und Strafvollzug. 2nd edition. Norderstedt 2011, 17.

[ii] Harald A. Dreßler, “betr.: alltagsrealität im knast”, in Ingeborg-Drewitz-Literaturpreis (ed.), Risse im Fegefeuer. Hagen 1989, 63-65.

[iii] Peter-Paul Zahl, “Der große Reso-Schwindel” in Karlheinz A. Barwasser (ed.), Schrei Deine Worte nicht in den Wind: Verständigungstexte von Inhaftierten, Tübingen 1982, 64-67 (64).

[iv] A.P. “Brief an den Staatsanwalt” in Birgitta Wolf (ed.), Die vierte Kaste: Junge Menschen im Gefängnis. Hamburg 1963, 144-49 (145-47); H., in Wolf (ed.), Die vierte Kaste, 274; Peter, in Klaus Antes et al. (eds), Lebenslänglich: Protokolle aus der Haft. Munich 1972, 84.

[v] Katharina, 116 and 119; Nationaler Stelle zur Verhütung von Folter 2017, 24; Markus Finke, “Arrest”, in Koch (ed.), Mit der Flaschenpost gegen einen Ozean: Briefe aus dem Knast. Münster 1998, 82-84 (83).

[vi] Anon., in Der Lichtblick 372 (2017), 17.

[vii] Peter Feraru, in Uta Klein and Helmut H. Koch (eds), Gefangenenliteratur. Hagen 1988, 118.

[viii] Karin Amann, “Eindrücke eines Jury-Mitglieds” in Ingeborg-Drewitz-Literaturpreis (ed.), Gestohlene Himmel: Widerstehen im Knast, Leipzig 1995, 12-15 (13); Karlheinz Barwasser, “Sich als starke Mauern begreifen” in Helmut H. Koch and Regine Lindtke (eds), Ungehörte Worte: Gefangene schreiben. Münster 1982, 107-11 (107-8).

[ix] Galli, “Von Mensch zu Mensch”, in Ingeborg-Drewitz-Literaturpreis (ed.), Begegnungen in der Welt des Widersinns, Zell/Mosel 2018, 9-12 (11).