Vincenzo Cammarata, PhD student at King’s College London, reviews Augusto Carlos’ Vovô Tsongonhana

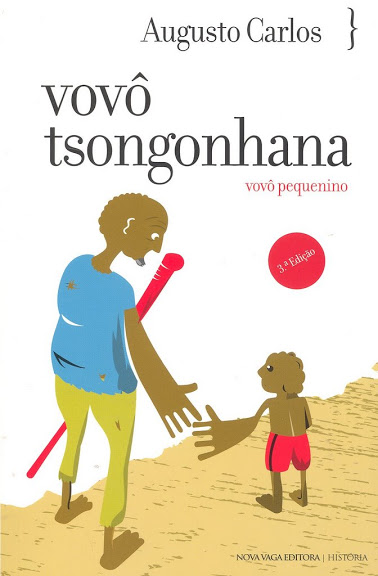

Looking at the simple things in life, Vovô Tsongonhana (2005) describes the lives of an old man and a child, searching for happiness and harmony with the surrounding world. The message of this book is clear: people should be grateful for what they have and help each other. Sharing is caring, as we all know. Speaking with the voice of an imaginary story-teller, Mozambican writer Augusto Carlos narrates the story of an old street seller from Congolote, who regularly goes to Maputo to sell his artefacts, and one day decides to take a child off the street. The plot is linear: an old man, Moisés, nicknamed Tsongonhana (meaning little, short), brings an orphan child home and teaches him manual jobs, such as carving statues made of mafurreira roots, so he can sell them and make a living from it. This nameless child, called by the others Bula-Bula for talking too much, is then named ‘Duda’ after Tsongonhana’s deceased brother.

A touching story filled with optimism. Despite all the difficulties encountered, Moisés doesn’t stop hoping. He lost his wife and his two sons vanished, so Duda becomes his new family and the promise of a brighter and prosperous future society, based on equality and justice. Tsongonhana gives daily lessons of life, discussing his views about today’s problems. In his opinion, people should look back in history and think of a way out of the misery brought by years of wars and corruption. Wars are always wrong, they separate families, displace people, many of them die, destroy everything and cause starvation. In a world where people raise up barriers and build up walls, Tsongonhana’s vision of a global community, where each member mutually supports each other for the greater good, is like a ray of light in this dark age of separations. The old man also acknowledges the concept behind the European Union, a broad form of international cooperation formed by several countries, including those that historically took part in the infamous Scramble for Africa. In his mind, Moisés wishes that every country of the world was included in such form of cooperation, supporting each other, in everyone’s interest.

The sun shines on everyone. To achieve happiness and freedom, Moisés thinks that men should try to find themselves by re-establishing a lost contact with the surrounding nature. Talking to plants, stroking them, staring at the beauty of the world are all part of a process of reconciliation to where we belong. Each human activity should be carried out in accordance with the rhythm of nature. Animals deserve respect and it’s necessary to give them some time to complete their biological cycle, it’s not all about satisfying human needs, even if you are a hunter. The mafurreira, mentioned several times in the book, is a symbol of self-sustainability, as this gives the raw material to make statues and sell them in the market, but is also an indissoluble bond between men and their land. These plants have feelings like humans, as the author makes them ‘wait’ to have their roots picked by Tsongonhana and Duda in the early morning, when the sun is rising. Mafurreira trees also ‘cry’ when the old man dies, but the author/story-teller doesn’t know if those are tears of nostalgic sadness or happiness for a future re-encounter. When the spirit of Moisés leaves his body like a mamba (snake) changes its skin, the narrator tells us that the mafurreira tree would soon host Moisés’s spirit, as it becomes the place where everyone commemorates Moisés on his final farewell.

‘Conversas à volta da fogueira’. For its colloquial language filled with local words coming from the Bantu languages spoken in Mozambique, Vovô Tsongonhana is meant to be read aloud. As a narration within a narration, the writer tells the whole story as if he is talking to his readers, who are sat around a fire, holding a conversation (conversas à volta da fogueira). Within this narrative frame, Moisés evokes his memories and tells stories of his life to Duda, as well as the other children of the streets of Maputo. The importance of talking face to face, sharing experiences, ideas, is part of a long educational process, moulding the characters and sharpening the minds of the future adults. Thanks to his oratory skills acquired through experience, Tsongonhana advocates the importance of the elderly in society and their educational role as an invaluable source of knowledge. Oral literature collects the stories of the predecessors with the help of memory, that writes, like an invisible ink, the pages of History. Without a clear-cut distinction between story and history in oral tradition, where the real and the fictional may mutually interfere, Moisés says that everybody’s history is the consequence of their parents’ lives, that, in turn, were the continuation of their parents’ lives, and so on, up to the very beginning of everything. Every story is important; even the smallest one, contributes to the development of history. People need to learn History to understand the present and build a better future.

A book about the little joys of life. What makes us happy? How do we achieve happiness? Living in a world where simple things tend to be overlooked or even ignored, this book is worth being read to gain a more positive outlook towards life. We need to know where we come from to understand who we are and where we are going to. Experience and mutual help build a healthy society, and Moisés knows it. The wise words of Tsongonhana are food for thought. Overall, I must say it is a short but very enjoyable reading; thanks to the words of the elderly man, Duda walks through an imaginary path towards a prosperous and harmonious world, surrounded by mafumeira trees, where everyone lives in peace with each other.

Vincenzo Cammarata, PhD student, SPLAS (Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies) King’s College London