To commemorate the 80th anniversary of the mass internment of refugees from Nazi Germany by the British government in May and June 1940, archivist Clare George will highlight over the next few weeks some of the stories of internment from the IMLR’s exile archives.

At the beginning of the Second World War, all Germans and Austrians in the UK were required to attend so-called enemy alien tribunals to determine the security risk they were thought to pose. The tribunals classified the 73,000 who attended into three categories, A to C, depending on the perceived level of their trustworthiness and loyalty to the UK. Fewer than 600 were classed as Category A, those posing a high potential security risk, who were then interned immediately. The majority, around 55,000, were classed as Category C, presenting no security risk; roughly the same number were also recognised officially by the tribunals as refugees from Nazi oppression.

During the spring of 1940, a press campaign against the refugees led by papers such as the Sunday Express and Daily Telegraph began to stir up public fears of foreigners as spies and fifth columnists. With Britain’s position in the war deteriorating and the imminent threat of a German invasion, popular support for the policy of mass internment grew. Under pressure from the military authorities, the government began the wholesale internment of nearly 30,000 Germans and Austrians, starting with Category B men and women in May 1940 and Category C men from 22 June.

One of the latter group was Paul Bondy, a Jewish aluminium exports manager and trade unionist from Germany. Bondy came to the UK in 1935, followed by his non-Jewish girlfriend Charlotte Schmidt in 1936, to evade the Gestapo. Bondy had been involved in the anti-Nazi underground movement in Bremen, and both Bondy and Schmidt had been arrested and imprisoned in 1935 for contravening the Nuremberg Race Law. Soon after their arrival in the UK they were married, and their daughter, Jo Bondy, was born in 1937.

In the UK Bondy initially managed to find temporary work through his business contacts, but at the start of the war he lost his job, and the family went through several years of severe economic hardship. At his tribunal in October 1939 he was recognised as a Category ‘C’ refugee from Nazi oppression, but eight months later, on 26 June 1940, he was arrested and taken to Chelsea Police Station.

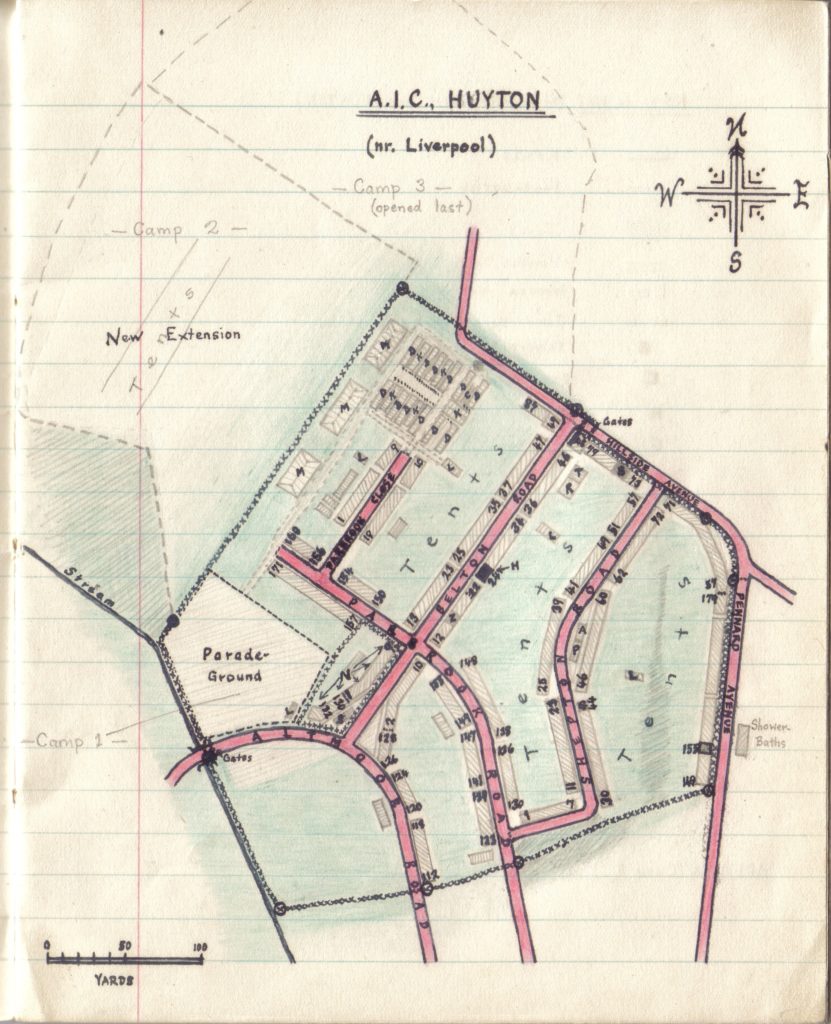

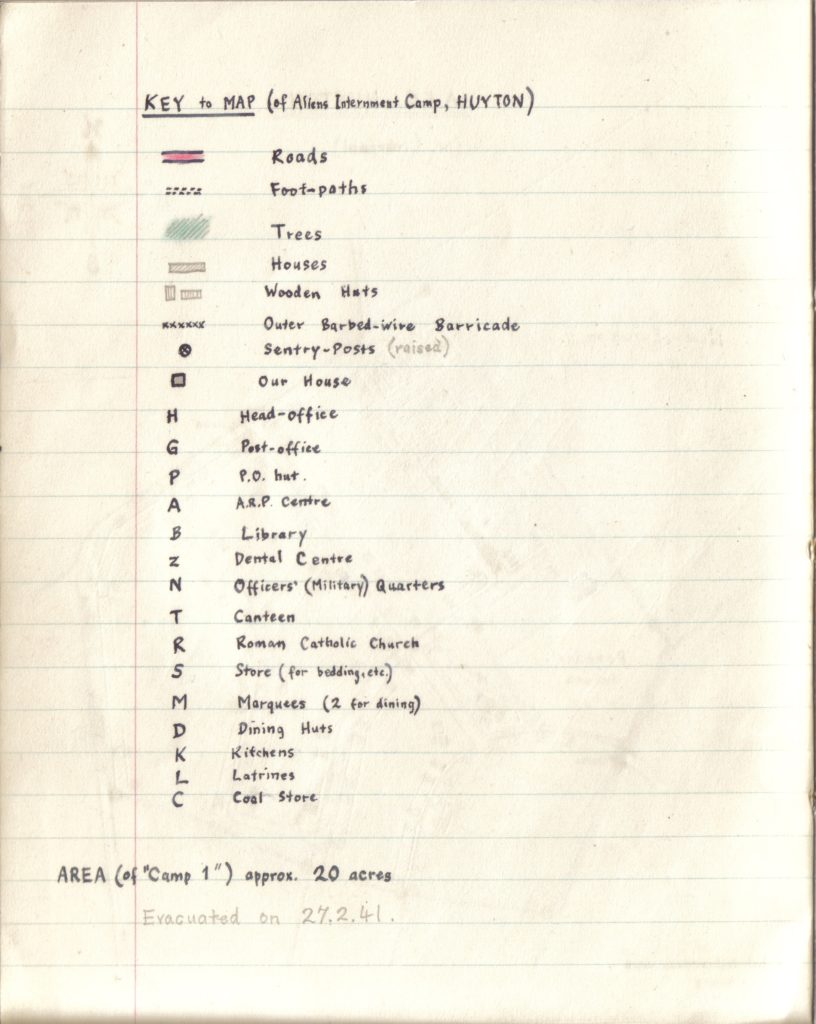

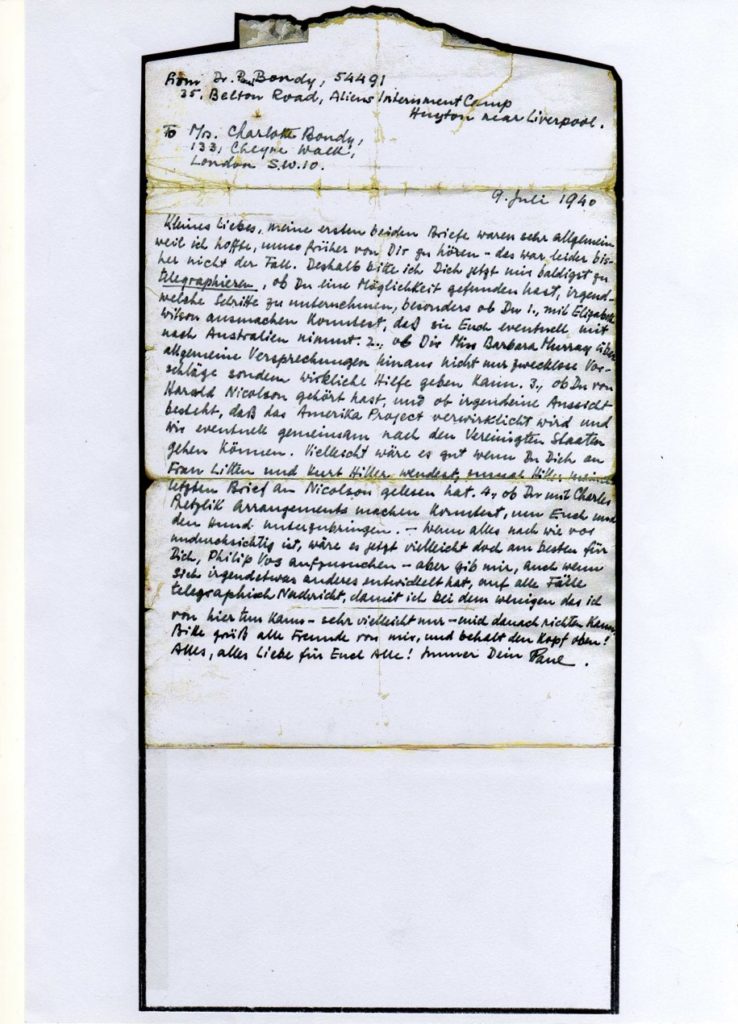

Bondy’s diary records in detail his arrest, detention at Kempton Park, and five-month detention at Huyton Aliens Internment Camp near Liverpool, the largest civilian internment camp on the British mainland. It includes notes on many of his fellow internees, like the Viennese art historian Otto Pächt and the trade unionist Hans Gottfurcht, and details of his and other socialists’ attempts to continue their political work despite their imprisonment. Other records give a fascinating insight into daily life and routine in the camp, including notices of meal and leisure arrangements, a notebook with the names of internees in each hut, and a hand-drawn plan showing the dining areas, the library and the post office. Extensive correspondence between Paul and Charlotte Bondy during his internment is dominated by their discussions about how to secure his release, which did not come until 6 December 1940, despite his application in August based on his status as a recognised opponent of Hitler.

After his return to London, Bondy campaigned for the release of other anti-Nazi activists still interned, including Gottfurcht, Eugen Brehm, Hans Ebeling and Kurt Hiller. He also continued his political work, writing a book detailing the opposition to Hitler in Germany in the 1930s, for which he sadly found no publisher. However, he had no steady paid work and the family lived in poverty, at times effectively homeless and reliant on the kindness of friends and refugee charities, until late 1941, when he finally found steady employment as a radio monitor with British United Press.

The Bondys’ archive, consisting of eight boxes covering the period 1917-1961, was generously added to the IMLR’s exile archives in 2017 by Rosalind Henderson; the donation was kindly arranged by Dr Jennifer Taylor of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, who worked with Jo Bondy on the archive. We are grateful to Dr Taylor for providing the digital images used in this blog post and for her help with interpreting some of the records.

The archive is in the process of being catalogued and a listing will be made available online by the end of 2020. Please note that the reference codes for the images given here are temporary – codes will only be finalised when the catalogue is published online.

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR