Professor Jean-Michel Gouvard reflects on the challenges of translating Shakespeare into French

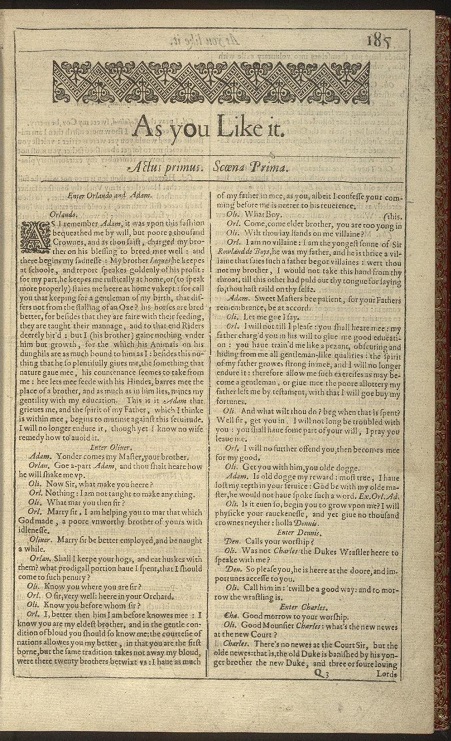

During the lockdown in France, it has been impossible to buy or borrow a book. So to help pass the time, I reread some of Shakespeare’s plays I had on my bookshelf. I do not work on Shakespeare or on Elizabethan theatre, but I really think he is one of the greatest writers of all time, and so thought he would be a pleasant companion for fleeing far away from the pandemic. Having said that, I also perceived an analogy between the changing and unstable world of the 16th century and the strange times we are going through now. Anyway, delighted as I was by many plays, scenes and lines, and wanting to share my love for Shakespeare with my (French) family, I tried to translate the Jaques’ famous “All the world’s a stage” speech from As you like it (2.7., 139–166). I soon discovered that, while reading Shakespeare had allowed me to escape Covid-19, translating him was a much more challenging proposition.

Let’s begin with the first sentence, “All the world’s a stage / And all men and women merely players”. I cannot render “all the world” by “tout le monde”, because “tout le monde” in French means “everybody”. A better translation might be “le monde entier” (“the entire world”). But, by doing this, I slow down the rhythm of the original: with Shakespeare’s sentence, we have only monosyllables, a verb reduced to a single consonant, “’s”, and a striking parallelism between the two nouns, “the world”/“a stage”. Perhaps it might be better to put “entier” to one side for now and to say “le monde est une scène/un théâtre” (see below for the translation of “stage”).

By losing the “all”, however, I lose another poetic effect: the parallelism between the two lines, “All the world” and “And all men and women”, which reinforces the shape of the sentence. Moreover, in this second line, “And all men and women merely players”, “all” remains a problem. “Et tous les hommes et femmes simplement des acteurs” would be awful, if not wrong, because in French we have a gender agreement: we must say “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes”. But a translation like “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes simplement des acteurs” still sounds weird. Such a sentence means something like “all men and women (are) just/simply players”, but it does not fit with the specific meaning of “merely”. To render it more effectively into French, we have to use a negative form, “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont que des acteurs”, or, with more emphasis: “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont rien d’autre que des acteurs”.

Coming now to the word “stage”, this can be translated into French by “scène”, “plateau”, “planches” (“board”), and sometimes by “décor” (“setting”). But what Shakespeare means is that the world is like a theatre, like a play that we, human beings, are all playing – a commonplace in European Renaissance literature. So, the most faithful translation seems to be “le monde (entier) est un théâtre”… but then I encounter a problem because of what the Duke Senior said just before that:

DUKE SENIOR

This wide and universal theatre

Presents more woeful pageants than the scene

Wherein we play in.

JAQUES

All the world’s a stage,

And all men and women merely players.

“Theatre”, “scene”, “pageants”, “(to) play”/“players”, and “stage”: within a few lines Shakespeare uses several more or less synonymous words to refer to the same thing. For “theatre” in “This wide and universal theatre”, I cannot think of a better word in French for this than “théâtre”, the same word I used to translate “stage” in “the world’s a stage”. Perhaps, then, in order to avoid the repetition or the elision of what appear to be different meanings, instead of “le monde (entier) est un théâtre”, I have to say “le monde (entier) est une scène” or “un décor” (“a setting”) or, why not, “une comédie” (“a comedy”). It is less faithful, but I can then avoid repeating a word that is not in the original.

Regarding the lexicon, I encountered some other problems. “Woeful”, a very Shakespearean word, could be translated by “triste” (“sad”) but also by “malheureux” (“sad”, “wretched”), “affligeant” (“distressing”, “grieving”) or “navrant” (“distressing”, “heartbreaking”), and I wonder if “tristes spectacles” is strong enough to render “woeful pageants”? Moreover, the French noun “acteurs” I used until now does not express the “old-fashioned” style we have in “players”. In France, during the Shakespearian period, we used the word “comédien” to refer to an actor; according to the Trésor de la langue française, “acteur” doesn’t appear with the meaning it has today prior to the 17th century (http://atilf.atilf.fr/). It might therefore be better to say “ne sont que des comédiens” instead of “ne sont que des acteurs”.

In the end, the whole section could be translated more or less faithfully by:

LE DUC: Cet immense théâtre universel offre plus de tristes spectacles que les planches sur lesquelles nous jouons.

JAQUES: Le monde entier est une scène, et tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont (rien d’autre) que des comédiens.

If we want to use “comédie” instead of “scène” (although Shakespeare said “stage” and not “comedy”), Jaques’ part could be rendered: “Le monde entier est une comédie, et tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont (rien d’autre) que des histrions.” This would avoid the repetition of “comédie/comédiens”: “histrion” is also an old French word, like “comédien”, that refers to a bad actor who exaggerates his performance (we can see this meaning in the English adjective “histrionic”.)

And you might ask: what of the poetry? And you would not be wrong to do so. This is what I asked myself too: by rendering Shakespeare’s text in simple prose, we miss something. I recommence my translation and try to put it in alexandrines, the “great French verse”, with its twelve syllables and its caesura after the sixth. In the end, I come up with the following lines:

LE DUC

Ce si vaste univers, cet immense théâtre,

Offre de plus navrants spectacles que les planches

Sur lesquelles nous jouons.

JAQUES

Le monde est une scène,

Hommes et femmes, tous ne sont que des histrions.

It is not a word-for-word translation, but we have now the rhythm of the alexandrine, “tatatatatata-stop-tatatatatata”, parallelisms (although they are not those of the original), and sentences with much expressive power. That is the version I prefer, although I really do not know if it sounds good or bad, or not too bad but not too good for English ears. But there is one thing I am sure of, it is that translation is indeed a very good hobby for lockdown times.

Professor Jean-Michel Gouvard, Université de Bordeaux Montaigne, France