Marc Olivier (Ulster University): My research mainly focuses on the syntax of Romance languages, with a particular interest for the Middle Ages. My doctoral thesis investigates the evolution of clitic placement in a corpus of French legal texts dating from the twelfth century to the nineteenth century. I analyse the development of French and compare it with the syntactic evolution of other Romance languages.

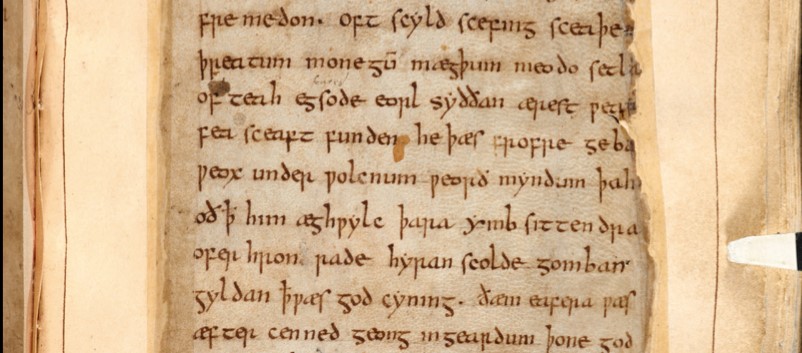

Ne hyrde ic cymlicor ceol gegyrwan hildewæpnum ond heaðowædum billum ond byrnum (Beowulf, 38-40). Unless you are familiar with the English language as it was written at the turn of the second millennium, this article probably starts with some gibberish to you. Beowulf, probably the most-known poem that was ever written in Old English, has become a window to the past. If one could travel back in time and ask the poet what language he wrote his verses in, he would probably answer with a shrug, “English”; and it would be absurd for him to say, “Old English”. Jumping back to 2020: our everyday speech is the same as our parents’ (although one might use some fashionable expressions that belong to their age category), and we also are able to communicate with our grandparents without having to Google translate every phone call they give us. Similarly, they would communicate with their parents and their grandparents, for they all spoke the same language, and so on. Should this actually be true, we would go back in time to our poet speaking a fairly identical English to the one I am using here. The solution to this issue lies in every speaker: new generations of speakers constantly bring in new alterations to the language, sometimes almost imperceptibly. During the last thousand years, it never happened that one day, English speakers went to bed uttering sentences like “ne hyrde ic cymlicor…” and woke up the next day speaking “Modern” English. In a thousand years’ time, 2020 English will probably be qualified as ancient too.

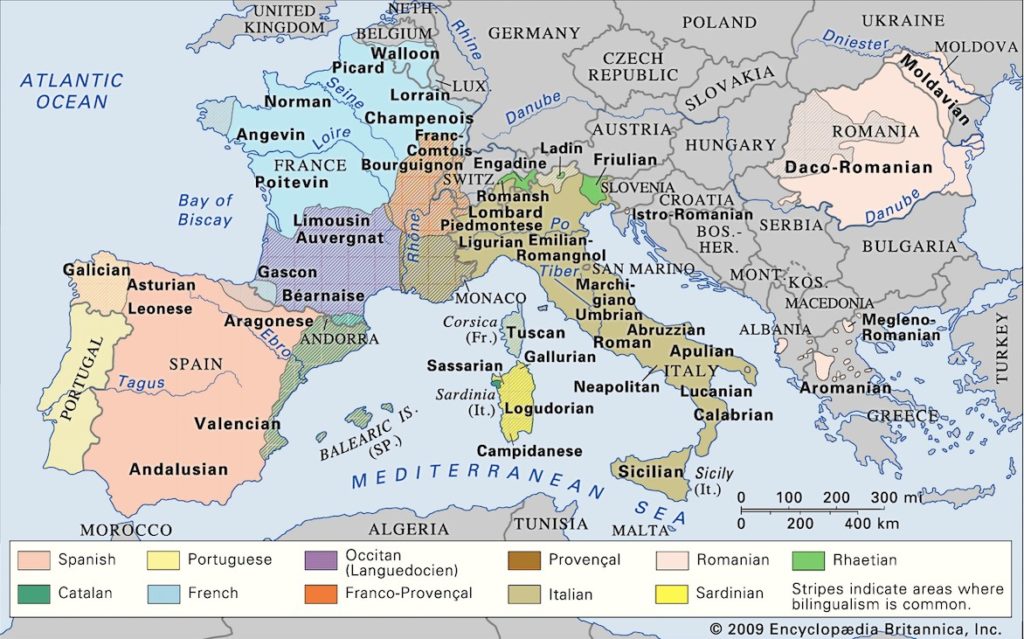

There is a subfield in linguistics that is dedicated to the study of language change: diachrony. My research focuses on Romance languages: at the fall of the Roman Empire, Latin was spoken in a great many places in Europe. Fifteen hundred years later, Latin is not gone: it has slowly evolved into Portuguese, Ladino, Occitan, French, Rumanian, Spanish, Romansh, etc. The Romance family counts many languages and dialects that emerged from Vulgar Latin.

Incidentally, many of them have developed a similar pronominal system, with the use of clitics: le, li, a, la, lo, o, me, mi, te, etc. Clitics are short pronouns that need to be ‘hosted’ by a word that is ‘stronger’, i.e. with full prosodic stress. In the Romance languages that have clitics, the host often is a verb: et veig, achète-le, la voglio, comerlo, etc. There is a quite well-established paradigm with clitics preceding conjugated verbs and following infinitives: this can be attested in Catalan, Italian, Spanish and others. Moreover, languages that follow the aforementioned paradigm have the option to remove the clitic from its infinitival host and place it before the conjugated verb. This can be illustrated in Italian “I can cook it”; posso cucinarlo – lo posso cucinare. However, French behaves otherwise. It allows clitics to precede the infinitive and forbids them from following it; it also lacks the possibility to allow a clitic to climb from its infinitival host to get hosted by a conjugated one.In order to understand why French is different, I have collected sentences with clitics from the earliest period that has available written material, i.e. the 12th century, until the modern pattern is established. Preliminary analysis suggests that Old French obeyed the paradigm and then drifted apart from its sisters. Change does not occur overnight, therefore my thesis covers seven centuries to understand and explain how change takes place, and why the structure of languages evolves.

Marc Olivier, PhD researcher in historical linguistics at Ulster University, Belfast.