The internment of nearly 30,000 so-called enemy aliens in May and June 1940 not only deprived those imprisoned of their liberty. It also broke up families already torn apart by exile, disrupted much-needed social networks and, in many cases, left dependants without support. In the second of a series of blogs commemorating the mass internment of refugees from Nazi Germany and Austria, Miller Archivist Clare George looks at what the archive of Austrian refugee artist Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag tells us about the impact on the family of the internment of her husband, Josef Berger.

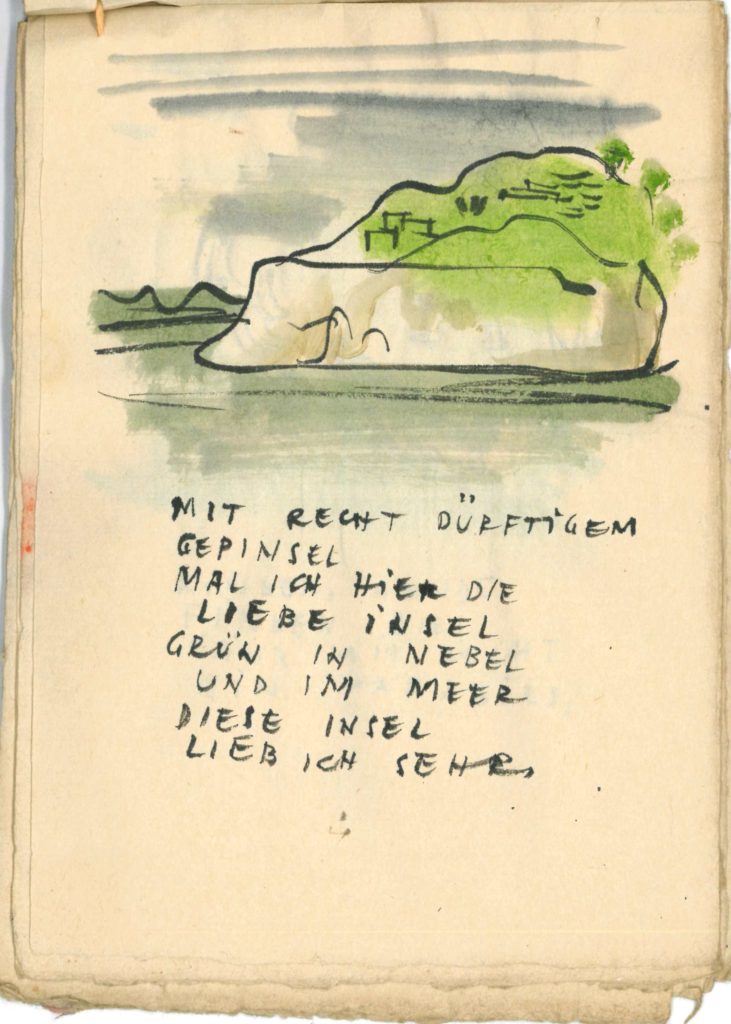

In 1920s Vienna, both Berger Hamerschlag and her husband had begun to establish themselves in their respective professional fields, she as artist and designer and he as architect and interior designer. By the 1930s however, work was becoming hard to find in impoverished Austria, and after the establishment of the Austrofascist regime, the couple emigrated. They spent two years in Palestine before settling in London in 1936, where their son Florian was born in 1937. In her artwork Berger-Hamerschlag reflected on her growing emotional attachment to the UK at this time.

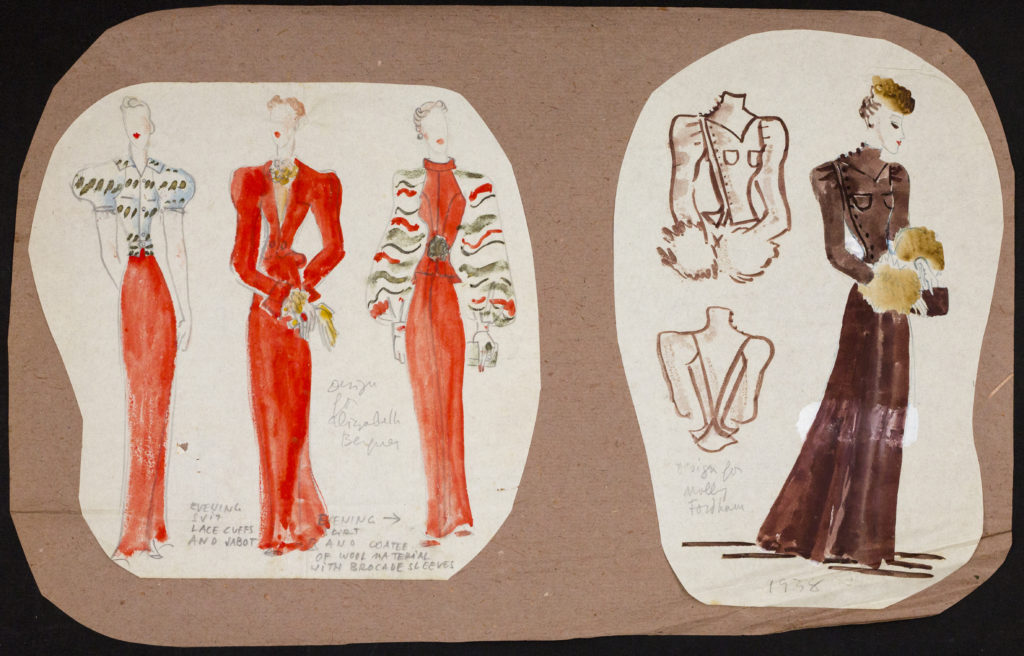

Their hope of returning to Austria disappeared with the Anschluss in 1938 and they focused on rebuilding their careers, making new friends and supporting other exiles in the UK. In the short time between arriving in the UK and the start of the war, Berger-Hamerschlag sold paintings, designed clothes for Elisabeth Bergner, Molly Fordham and the News Chronicle and had her work displayed at several international exhibitions, including the Unity of artists for peace, democracy, and cultural development in 1937. Her financial position remained insecure however, and she was dependent on her husband Berger, who achieved some success in architectural competitions.

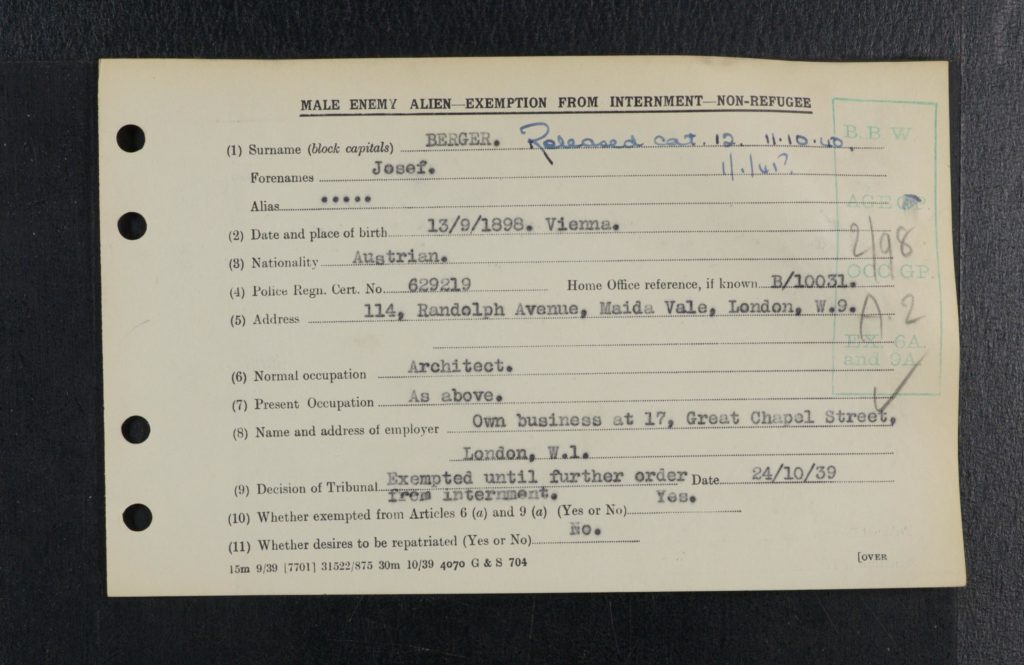

On the outbreak of war, Berger was called to attend an ‘Enemy Alien’ tribunal where, like 55,000 others, he was assessed as a Category C (no security risk) and exempted from internment, as his Home Office record at The National Archives shows. Eight months later, however, with rising anti-alien hysteria whipped up by the press and the decision to ‘collar the lot’, Berger was deemed a threat to national security after all and interned along with around 27,000 other Germans and Austrians.

The trials and hardships Berger-Hamerschlag went through whilst her husband was interned are documented in the hundreds of pages of letters Berger-Hamerschlag wrote to her husband at this time. The pain of their separation at such a difficult time was made worse by the dismal postal communications between the camp and the outside world. Three weeks after his arrest she had still received no word from him, as she complained in a letter to the censor of Mooragh Camp, Isle of Man, where he was being held. The postal system improved only slightly little over the following months.

The highlight of the letters for Berger were probably the updates on three-year-old Florian, whose interest in drawing and art was growing, stimulated perhaps by the stories and illustrations Berger-Hamerschlag created for him. The letters also gave news of refugee friends. On 7 September, for example, Berger-Hamerschlag reported joyfully that she had seen her brother-in-law Fritz Lampl, who had just been released from internment. However, much of what she wrote must have concerned Berger greatly. Payments she had relied on from the Unemployment Assistance Board had stopped while Berger was interned, and she was surviving on a bare minimum of food. Berger had to write to the UAB from Mooragh Camp to ask for more support for his wife and request that they be reinstated urgently. A letter a few weeks later confirmed that she would now receiving the grand sum of 25 shillings a week (less than £50 in today’s money) to pay the rent and buy food for herself and their child.

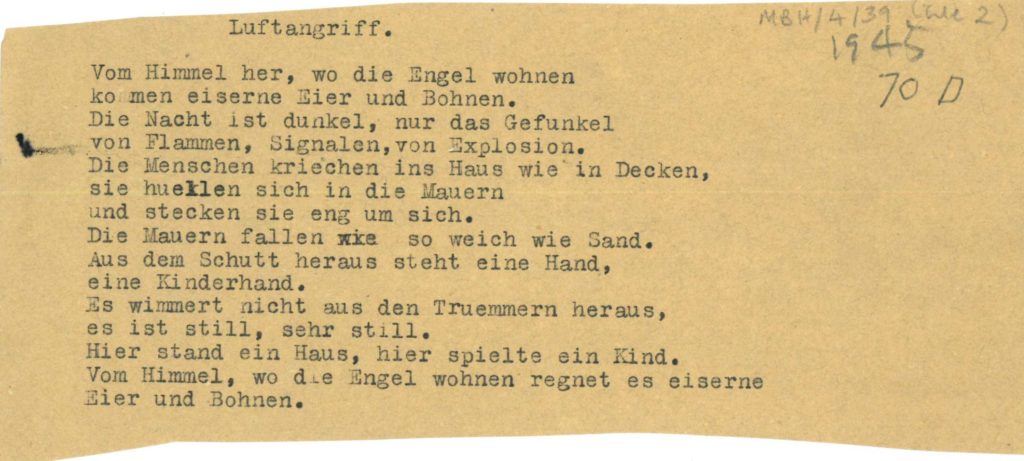

Another cause of anguish was the Blitz, which began two months after Berger’s internment and was accompanied by fears of a German invasion. Anti-German sentiment was running high, and Berger-Hamerschlag’s British neighbours clearly had little understanding of the difference between the German enemy they read about in the newspapers and the Austrian refugees in their midst, a letter from 14 September 1940 suggests. A week later, she and Florian faced a still worse when a bomb hit their house. They both survived but were now homeless, dependent entirely on friends and charity. Berger-Hamerschlag later reflected on the trauma of the Blitz in an unpublished poem ‘Luftangriff’.

The ordeal caused by the family’s separation came to an end only in late December 1940, when Berger was released after an appeal by a number of prominent figures in British art and architecture including Scottish artist, Sir Muirhead Bone, who was then on the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, his son the artist Stephen Bone, the art critic Eric Newton, and RBA Fellow Professor Charles H. Reilly. Soon after his release Berger was employed by London County Council to work on post-war town planning under Sir Patrick Abercrombie, and after the war the couple remained in the UK and gained citizenship. The publication of Berger-Hamerschlag’s book Journey into a Fog, recounting her experiences of teaching art in deprived London youth clubs in the 1950s, finally brought Berger-Hamerschlag financial independence in 1955. She had little time to enjoy this success, however, as she sadly died of cancer in 1958.

Berger-Hamerschlag’s papers were donated to the IMLR in 2010 and are now managed by Senate House Library on behalf of the Institute. Dr Anna Nyburg of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies carried out the initial sorting of the material and we are grateful to her research which has helped with interpreting some of the records. Further information about the archive can be found here and an online catalogue of the archive can be found here.

Read more Stories from the Exile Archives

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR.

Very interesting, and sad in some ways- though the couple made it through. What happened to little Florian I wonder?

In response to Catherine Davies, little Florian changed his name to Raymond when he went to Grammar School in Marylebone in 1949. Many reasons for that. He went on to become a theatre and TV designer, worked for the BBC and many others. Left London after taking a teaching job at an art school in Exeter Devon and has lived there for 35 years. Now aged 82 has had two marriages and three sons plus six grandchildren and has been a full time artist since 1989

Wonderful to know! What a happy story. Thank you.

This account truly reflects some the many hardships caused by internment. The illustrations are delightful, and the Exemption from Internment certificate is of particular interest, since few people seem to have retained them. A splendid collection for the archive!

Thanks very much for the comments. For more on Raymond Berger’s work as an artist, see http://www.raybergart.com/.