The internment of nearly 30,000 of the 80,000 refugees from Nazi Europe in the UK in the summer of 1940 disrupted community organisations and the vital support networks which provided a measure of relief to the traumatised refugees. Austrian Jewish exile actors Martin Miller and Hanne Norbert were active in a number of these organisations, notably the Austrian exile theatre, the Laterndl. In this blogpost Miller Archivist Clare George looks at some of the records in their archive for evidence of how mass internment in the summer of 1940 affected such organisations.

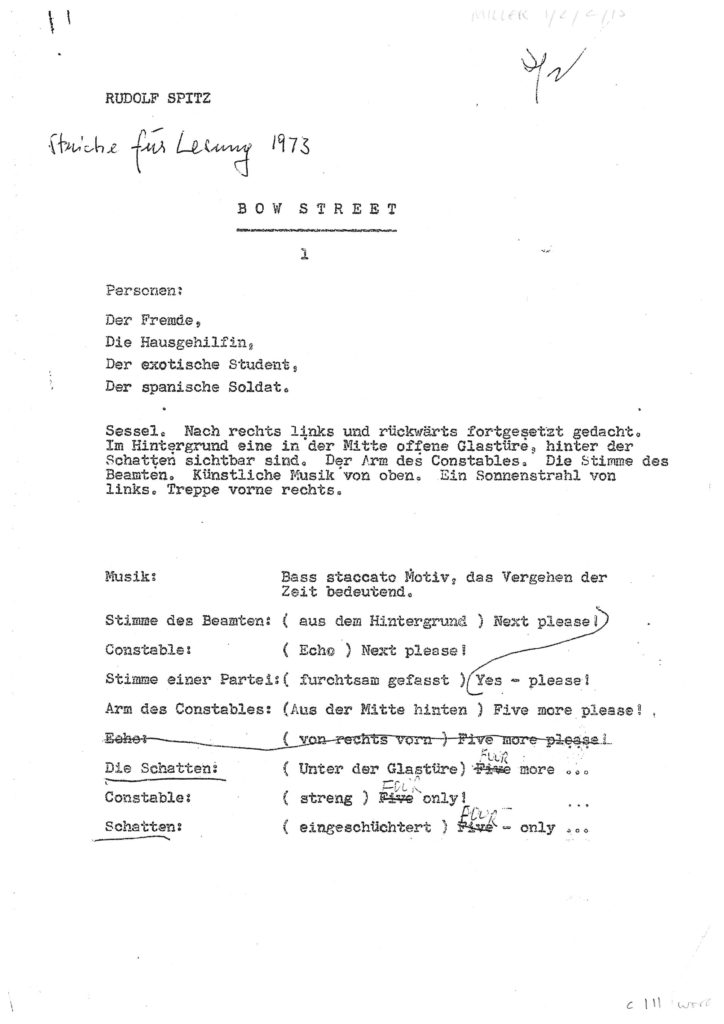

The Austrian exile theatre was established in the spring of 1939 with the aim of contributing to the fight against Nazism and in the first year of its existence it provided an opportunity for the refugee community to share stories and the experience of exile. The theatre reflected on the issue of hostility to the refugees in UK in the sketch ‘Bow Street’ by Rudolf Spitz, which was staged in the company’s first production, Unterwegs, in June 1939. Set in Bow Street Magistrates Court, the sketch saw the trial of three refugees being overseen by Judge Commonsense, General Bias and Mrs Charity. The Times described the sketch as the theatre’s ‘most ambitious piece, … which reflects upon the grim present’ and The Spectator reported that the sketch had ‘a real and unforced pathos that brought tears to the eyes of weaker members of the audience’. The scene appeared almost to anticipate the ‘enemy alien’ tribunals that would start a few months later, with the positive outcome of the trial and Mrs Charity’s triumph over General Bias perhaps reflecting the gratitude to the UK felt by many newly-arrived refugees in 1939.

This early sketch was in fact unusual in its focus, since the Laterndl players aimed their satire principally at Nazi leaders and developments in Austria and Germany. In March 1940, as the UK’s press was demanding the imprisonment of the refugees as ‘spies’ and ‘fifth columnists’, the company produced one of its most popular anti-Nazi shows, The Eternal Schwejk. In April 1940 the actors began rehearsals for a new production of Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper, and in early May the theatre group was confident enough of its future to plan the publication of a yearbook to mark the first anniversary of its existence. By the time the Dreigroschenoper opened in late May however, the mass arrests had begun, and the company struggled to keep up with the loss of the actors to the internment camps. When first one and then a second actor playing the role of Mackie Messer was interned, the challenge of finding a third was just about met but it was clear that the theatre would have to suspend its activities.

In August the remaining company members attempted to re-open the theatre. With the support of the Laterndl’s patrons, PEN members Janet Chance, Herman Ould and Storm Jameson, they wrote to the Advisory Council on Aliens at the Foreign Office for support. One of the Council’s functions was ‘to suggest measures to maintain morale for aliens in this country so as to bind them more closely to our common cause’. Pointing out that the theatre had been run ‘solely by exiled anti-Nazi writers and actors’, receiving ‘considerable publicity’ and ‘good audiences’, Laterndl writer Rudolf Spitz asked if the theatre could apply for ‘a grant to ensure its first expenses’. How the Council responded to the Council is not known, but in any case the theatre did not reopen at this point.

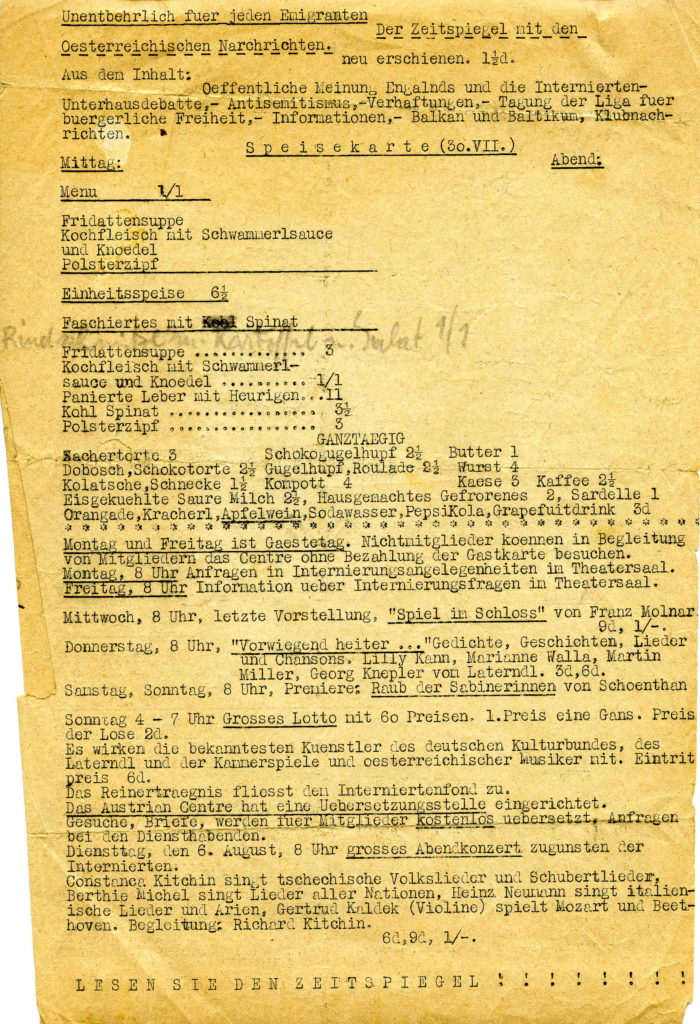

The Laterndl’s parent body, the Austrian Centre near Paddington, London, also came under severe strain through the crisis, with many of its staff and most of its members interned. The Centre had been established by Austrian Communist refugees in March 1939 and by 1940 it was the largest Austrian exile self-help organisation in the UK. This newssheet from 30 July 1940 documents some of the ways it responded proactively to the challenge of mass internment in support of the community. Meetings and information events were held twice weekly to provide support and practical help for those whose loved ones had been arrested. The Centre’s newspaper, the Zeitspiegel, led with articles on wider UK public opinion on internment and debates in the House of Commons.

The Centre also launched an entertainment programme of concerts and literary performance to raise funds for the internees. Some of the Laterndl actors who had not been interned contributed to the programme, amongst them Martin Miller. In a fascinating oral history interview carried out by Charmian Brinson in 1995 with Norbert (by then Hannah Norbert-Miller), the latter revealed that it was in fact Miller’s work at the Centre and the Laterndl which had indirectly enabled him to avoid internment in June 1940. Miller, who had been classed as Category C (no security risk) at a tribunal in October 1939, was then living in Putney in south west London. It was a considerable journey from there to both the Laterndl at Swiss Cottage and the Austrian Centre at Paddington, and to save on fares Miller would stay at work and sleep in the offices overnight. When the police came to arrest him early in the morning in June 1940, they were therefore met with the simple message that he was away from home, at which point they appear to have given up. Norbert-Miller commented that this was ‘a thing I just can’t understand. Instead of thinking this very suspicious, they just never bothered to find him. I used to meet him in Marble Arch, courting at 6 o’clock in the morning’.

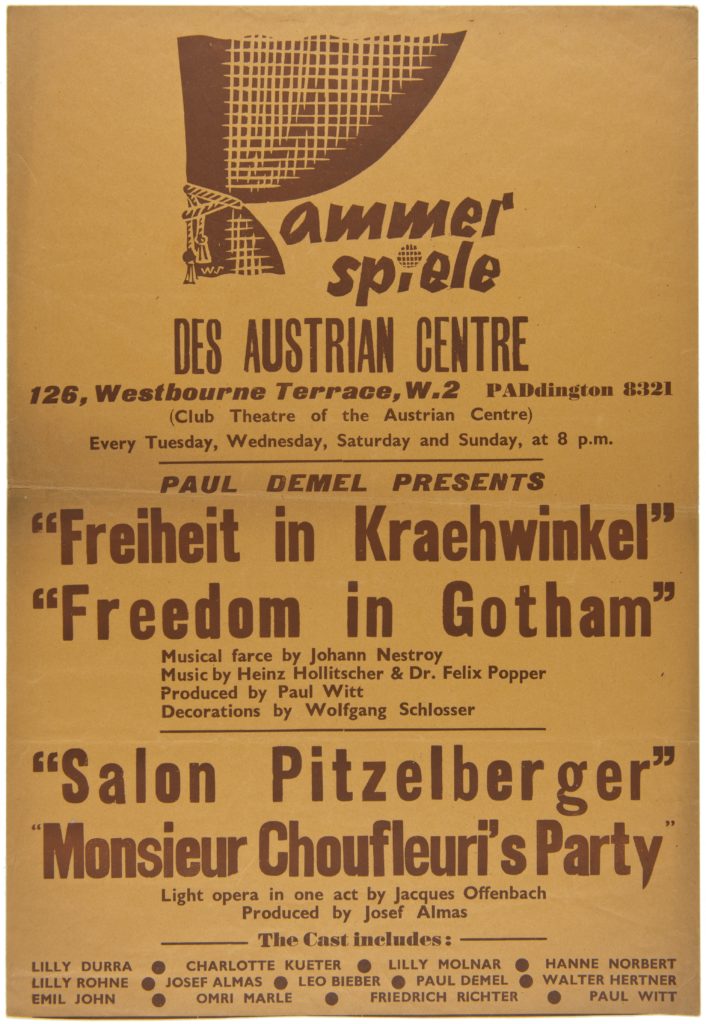

As well as the programme of weekly concerts and literary events for fund-raising at the Centre, space and support was also given to a new theatre group, the Kammerspiele des Austrian Centre. The group brought together actors from the Laterndl who had not been interned, including Hanne Norbert and Lilly Durra, with those in a similar position from the Free German League of Culture, which had also been forced to close. The Kammerspiele also involved a number of German-speaking refugee actors from Czechoslovakia, who were not under threat of mass internment since they were considered to be ‘friendly aliens’. Very few traces of this theatre company have survived but this poster shows that their productions included Nestroy’s Freiheit in Kraehwinkel and Offenbach’s Salon Pitzelberger. The company probably did not last more than a few months, however, and it was more than a year before the community could announce it had a fully functioning theatre again, with re-opening of the Laterndl in new premises in September 1941.

This blogpost draws on research by Professor Charmian Brinson and Professor Richard Dove into the archive of Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller. The archive was kindly deposited at the IMLR by the Millers’ son Daniel Miller in 2001 and is managed by Senate House Library on behalf of the Institute. Further information about the archive can be found here and an online catalogue of the archive can be found here.

Professor Brinson’s oral history interview with Hannah Norbert-Miller was carried out in 1995 as part of a series of interviews carried out by members of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies with German-speaking refugees from Nazi Europe. Further information about the interview is available here.

Read more Stories from the Exile Archives

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR.