Nora Baker (Jesus College, Oxford): I am a second-year PhD student researching the self, humility, and cultural influences/pressures in memoirs written by Huguenot refugees in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, a law which had previously granted a certain degree of religious freedom in France. The Revocation effectively banned Protestantism in the kingdom, though policies aimed at eradicating French adherents to the reformed religion – known as ‘Huguenots’ – had been steadily increasing since the debut of the Sun King’s reign. 1681 saw the launch of the dragonnades, a practice which forced Huguenot families to harbour state soldiers in their homes, and provide for their feed. In return, these soldiers were instructed to harass their hosts and attempt to convert them to Catholicism.

Artist’s impression of Gamond from an English translation of her memoir, entitled Blanche Gamond: a French Protestant Heroine (1870)

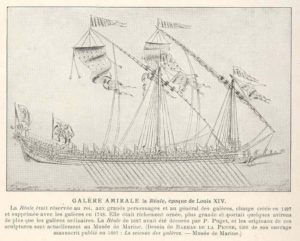

In light of the oppressive measures taken by the Crown, it is not surprising that the late seventeenth century saw something of an exodus of Huguenots from France: an estimated 150,000-200,000 left for countries where they could practise their faith without interference. The road to exile was often fraught with danger, however – women who were caught risked being locked up in convents or prisons, and men could be condemned to servitude on the King’s galley ships. Many of those Huguenots who managed to safely settle aboard composed accounts describing their experiences of escape and confinement. My thesis explores the portraits that authors of such texts sought to craft of themselves and of their lives.

I look at the autobiographical writings of imprisoned women, enslaved men, and of refugees trying to put down roots in new lands. These authors may have experienced persecution in different ways, but they share an adherence to an established minority religious culture which informs both their narrative choices and their personal concerns. Formed amid the turmoil of the sixteenth-century civil wars, French Protestant writing counts the concept of martyrdom among its most prevalent topoi, and post-Revocation texts are no exception to this focus. Many authors appeal to their readers’ sympathies by showcasing how they have followed in the footsteps of models of piety documented in martyrological volumes. The writers I study did not actually face death for their faith – all eventually managed to escape France and penned their memoirs in exile – but we are often encouraged to interpret their stories, and the suffering depicted therein, as akin to the violence endured by believers who did die. Blanche Gamond, a young woman who was incarcerated in Grenoble and Valence, peppers her narrative with scenes that mirror or echo the actions of those souls who feature in the most popular French Protestant martyrology, Jean Crespin’s Histoire des Martyrs.

Title page of the 1619 edition of the Histoire des Martyrs (continued after Crespin’s death by Simon Goulart)

Though the last edition of Crespin’s edition was published in 1619, it maintained its place as a treasured text for the Huguenot community into the dawn of the eighteenth century: memoirist Jean Migault recalls his wife taking comfort from the tome as she lay on her deathbed in 1683.[1] The cultural memory of persecution faced during the Wars of Religion helped Huguenots living under Louis XIV build a framework to understand suffering in their own time: pain was a virtuous thing, a sign of God’s favour, rather than of disgrace. Jean-François Bion, a convert to Protestantism after a posting as a galley chaplain, shows in his account of ship slaves that even new members of Huguenot society were wise to the value the community placed on victimhood. Conscious of his former association with the oppressor, Bion takes care to emphasize his presence among the enslaved, caring for their wounds, listening to their stories, receiving praise from them for his open-mindness even before his conversion. He symbolically lowers himself to their level and links his fate to theirs as he describes how his own clothes became infected with the same vermin that afflicted the slaves.[2] To the Early Modern French Protestant society, this humble status was much more honorable than the earthly glory available to Nicodemites.

[1] Migault, Jean, and Yves Krumenacker. Journal de Jean Migault, ou, malheurs d’une famille protestante du Poitou, 1682-1689. Les Éditions de Paris Max Chaleil, 2011, p. 50.

[2] Bion, Jean François, and Pierre M Conlon. Jean-François Bion et sa Relation des tourments soufferts par les forçats protestants. Librairie Droz, 1966, pp. 86-87.

Nora Baker, PhD student, University of Oxford

Fascinating!