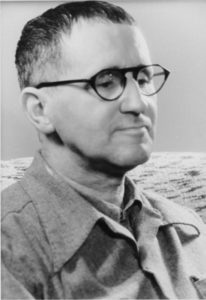

On Bertolt Brecht’s 123rd birthday, actor Jack Tarlton and playwright Stephen Sharkey look back at their Brecht in Song workshop held as part of the OWRI project in September.

Jack Tarlton: It started with the choice of books that I took into lockdown with me in March 2020, which included Bertolt Brecht’s Collected Plays: One. As I worked my way through the scabrous life of Baal in the first of the nine plays, I was struck by how the flint-edged street language of each scene seemed to trip itself up and become less clear and robust when it came to Baal’s songs. The imagery became cloudy and the forward momentum lost. I was intrigued by this, and although not a translator, lyricist or musician, I have been lucky in my role as an actor and director to have worked closely with those who are. I therefore thought it would be interesting to bring together a group of translators curious about the world of theatre and song, and five actor-singer-songwriters into a virtual workshop environment to see what would happen. Could they forge new versions of the songs of Brecht that lived and breathed as short dramatic performances?

First, though, I asked a previous collaborator, the playwright, adaptor and lyricist Stephen Sharkey – whose new version of Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui had been produced at the Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse – to join me in preparing the workshop. Together we researched Brecht’s life and plays and selected the five songs that we would rework. Five songs that each provided a specific idiosyncratic challenge – ‘Der Choral vom großen Baal’ from Baal, ‘Das Lied von Fluss der Dinge’ from Mann ist Mann, ‘Lied vom Flicken Und Vom Rock’ and ‘Bericht über den Tod eines Genossen’ from Die Mutter, and ‘Obacht, get Obacht!’ from Die Heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe. Supported and hosted by the Institute of Modern Languages Research, we were ready to see if the experiment would work.

On Friday 18 September we all gathered online, and after a session in which I shared my research on the importance of music and rhythm on the life, health and artistic development of the young Brecht, Stephen shared his own adaptation of ‘Das Lied vom Weib des Nazisoldaten’ from Schweyk im Zweiten Weltkrieg. The international group of translators gave their feedback to it, before the performers each took a verse and quickly collectively performed their own rough ‘n’ roll take on the song. After lunch I allocated a song and a team of translators to each performer, and they were off into their own break-out rooms to discover what they could create together.

My research had revealed that the adolescent Brecht had a close circle of friends and collaborators who would meet regularly in his attic to create verses, songs and short plays. As the workshop progressed it felt to me as though we were widening and diversifying that circle and making it our own. Brecht and his friends would then gather in a local tavern to share their work. Our tavern was the online gig that we held that night, where each song, reworked in a matter of hours and all truly alive and strikingly relevant were sung loud to an eager audience.

Below, published for the first time, are those five new versions of Brecht in song.

Stephen Sharkey: Translating the words of a song from one language to another is a devilishly difficult undertaking. How to convey the complexity and vivacity of great lyrics, the gut feeling here, the twisty-turny ironic word-play there, the explosive energy in another place? The linguistic fingerprint is impossible to replicate perfectly. But we have to try – few of us are able to read and fully appreciate songs, poetry, lyrics in a language foreign to us. For me as a playwright grappling with Brecht’s singular genius armed only with rudimentary German, existing translations and a decent dictionary, the Brecht In Song workshop was a revelation. The professional translators who Zoomed in from around the world – live from a cafe in Istanbul, or from a sitting room in Berlin – brought their urbane, incisive expertise to bear on the five Brecht songs we chose to explore.

First though, it was a real shot in the arm to have them read aloud and comment on my work-in-progress translation of ‘The Song of the Nazi Soldier’s Wife.’ Their enthusiasm was infectious, their rigour and focus impressive, and all these qualities were evident when they partnered up with our brilliant actor-musician-performers to make their own versions of the five songs.

After a whirlwind afternoon’s collaboration, an online audience gathered round their laptops to listen in to Aminita, Hannah, Jochebel, Michael and Robert, performing songs from four of Brecht’s plays. I had not expected to have quite so emotional a reaction to the pieces, but each had its own goad or sting or attack – Brecht (and collaborators) really knew how to land a line like a punch to the gut. It was a powerful reminder of how front-footed, scabrous, and vigorous is the voice of Bertolt Brecht in his plays and poems. I was moved by the voices, the physical presence of the singers, their gaze – even down a below-par internet connection. It was a painful reminder of what we’re all missing in 2020, how we need the shared experience, to be in rooms together. And how much we miss the theatrical room, in all its many forms.

Jack Tarlton is a Scottish actor, director and teacher. His stage work includes lead roles with the National Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company, Young Vic and the Royal Exchange, Manchester. Screen work includes The Imitation Game, 8 Days to the Moon and Back, Traces, Outlander, Doctor Who and The Genius of Mozart. He has taught Shakespeare and modern drama studies and adapting prose and translating for the stage at the University of London, University of Buenos Aires, Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Oxford University, East 15 Acting School and for The Old Vic and Out of Joint, and was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Modern Languages Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He can be found on Twitter @jacktarlton.

Stephen Sharkey has translated and adapted a wide variety of classic and classical stories for the stage, including works by Euripides, Aristophanes, Wilde, Defoe, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Dickens and Goncharov. His most recent work includes an adaptation of WHITE TEETH, Zadie Smith’s modern classic novel, in a major production at the Kiln Theatre by artistic director Indhu Rubasingham, a version of Tolstoy’s THE DEATH OF IVAN ILYICH for one actor, and INKHEART, adapted with Walter Meierjohann from the children’s novel by Cornelia Funke for Home, Manchester. His new translation of Brecht’s THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF ARTURO UI was commissioned and co-produced by Liverpool Everyman & Playhouse and Nottingham Playhouse. He can be found on Twitter @steshark.

It was a great workshop – a chance to enjoy the emotional vigour of Brecht’s songs and blitzthink what that might sound like in English.