Transnational and decolonisation approaches are shaping the present and future of Modern Languages, which makes the dialogue between research and teaching more important than ever before. Marcela Cazzoli and Liz Wren-Owens discuss whether we are ready for the challenge.

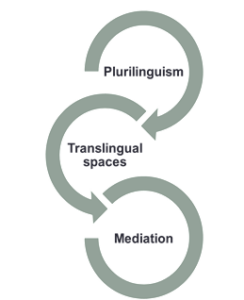

The keystone Transnational Modern Languages project was fundamental in encouraging an overdue transformation in the discipline, identifying a set of issues that research and teaching in Modern Languages would need to challenge to remain sustainable and relevant and to ensure that the true value of the discipline was clearly legible to those outside the subject area. The TML project enabled us to reframe the disciplinary framework of Modern Languages, arguing that it should be seen as an expert mode of enquiry whose founding research question is how languages and cultures operate and interact across diverse axes of connection. Central to the debate was the interrelationship between languages and cultures and the necessity to leave monolingual traditions behind, to uphold the real picture of how languages engage with the contemporary global world.

Those of us teaching in schools of Modern Languages have known about this first hand: we are incredibly lucky to be surrounded by different languages and immersed in a wealth of linguistic and cultural diversity that we sometimes take for granted. Yet, our curricula may still hold us back, reflecting a vision of Modern Languages teaching and research that sees culture through the lens of language, and language through the lens of skills. The (Re)Creating Modern Languages project (Beaney et al, 2020), for instance, has provided guidance on how we might think about revising our curricula, identifying areas to consider in terms of structures of programmes, engagement with the wider socio-cultural perspective, the scope of our cultural focus, and identifying (and overcoming) barriers to change.

If we are serious about engaging our students with a discipline that reflects the reality of the transnational, translinguistic, and transcultural world of today, a global understanding of languages that works in synch with decolonising approaches is crucial. Are we committed to tackling the linguistic indifference of postcolonial studies? How complicit are we in allowing Anglo words and Eurocentric frameworks to dominate the narrative of practices and identities? Decolonisation projects developed in universities across the UK have provided further support to transnational approaches, as they both aim to decentre and challenge methodological nationalism and propose an inclusive view of multilingualism and multiculturalism.

How do we use transnational and decolonising approaches to design our teaching? The Transnationalising the Word symposium began a conversation that has hopefully raised awareness and provided some reassurance that it can be done. The well-thought out presentations, linking research with practice, provided examples and insights for the way forward. We have been able to ask ourselves very useful and, at times, uncomfortable questions that can help us think through how we might revise our programmes or curricula. In his opening paper, Decolonising the Chinese Curriculum: Indigenous Epistemology and Translanguaging, Danping Wang discussed how different epistemological approaches can reframe the learner-teacher relationship and asked us to unlearn our current assumptions and  open up our imaginations. This notion of unlearning and opening is a powerful notion that can shape our approach not only to questions of transnationalising and decolonising our curricula, but in thinking through our teaching more broadly. Other presentations throughout the day further probed how connections and collaborations might be fostered between languages and culture, and the ways in which languages other than English are valued as effective means of resistance to (mental) colonisation. Excellent projects were showcased which suggested practical ways of shaping our teaching and, importantly, our assessment, to enable students to engage with the ways in which culture shapes languages and both are informed by power dynamics often linked to colonial histories. Alexandra Lourenço Dias’ Decolonised Dictionary of the Portuguese Language Project, for example, explored how students can reflect on the interrelationships between language, culture, and power through the development of an exciting new resource that focuses on terms are that articulated differently in parts of the Portuguese-speaking world based on the local culture and their history. Angela Viora’s presentation, Cities, Landscapes, and Ecosystems: Exploring Contemporary Italy Through Local Responses to Global Challenges. Creativity, Interdisciplinarity, and Decolonisation and Salvatore Campisi’s Reflecting on and Challenging Narratives of Italy and Italian with Students opened up questions of how transnationalising and decolonising the curriculum might enable us to re-think the cultural materials that we study. They offered fascinating examples of how street art, itinerant performers, oral histories sourced by students from the local community, rap, and public statues and memorials can be leveraged to encourage students to reflect on transnational and decolonising histories. Viviane Carvalho da Annunciação’s work on Decolonising Portuguese Language Classes explored the extent to which the diverse backgrounds that students bring to the classroom are reflected (or not) in pedagogical practice and examined how our practice be adjusted to enable and empower students from minority backgrounds, from the study of languages in schools through to undergraduate programmes.

open up our imaginations. This notion of unlearning and opening is a powerful notion that can shape our approach not only to questions of transnationalising and decolonising our curricula, but in thinking through our teaching more broadly. Other presentations throughout the day further probed how connections and collaborations might be fostered between languages and culture, and the ways in which languages other than English are valued as effective means of resistance to (mental) colonisation. Excellent projects were showcased which suggested practical ways of shaping our teaching and, importantly, our assessment, to enable students to engage with the ways in which culture shapes languages and both are informed by power dynamics often linked to colonial histories. Alexandra Lourenço Dias’ Decolonised Dictionary of the Portuguese Language Project, for example, explored how students can reflect on the interrelationships between language, culture, and power through the development of an exciting new resource that focuses on terms are that articulated differently in parts of the Portuguese-speaking world based on the local culture and their history. Angela Viora’s presentation, Cities, Landscapes, and Ecosystems: Exploring Contemporary Italy Through Local Responses to Global Challenges. Creativity, Interdisciplinarity, and Decolonisation and Salvatore Campisi’s Reflecting on and Challenging Narratives of Italy and Italian with Students opened up questions of how transnationalising and decolonising the curriculum might enable us to re-think the cultural materials that we study. They offered fascinating examples of how street art, itinerant performers, oral histories sourced by students from the local community, rap, and public statues and memorials can be leveraged to encourage students to reflect on transnational and decolonising histories. Viviane Carvalho da Annunciação’s work on Decolonising Portuguese Language Classes explored the extent to which the diverse backgrounds that students bring to the classroom are reflected (or not) in pedagogical practice and examined how our practice be adjusted to enable and empower students from minority backgrounds, from the study of languages in schools through to undergraduate programmes.

A few presentations offered useful insights into how the publications emerging from the Transnational Modern Languages project, in Liverpool University Press’ Transnational Series, might provide teachin g tools as we re-think our approach to teaching language, culture, and history. Derek Duncan & Jenny Burns’ presentation on Thematic Cartographies: Transnational Modern Languages and Cecilia Piantanida’s Hybridity and Transnationalism in the Modern Language Class suggested ways of challenging student preconceptions of cultures and nations by adopting a transnational and decolonising approach to teaching, thinking through how idealised and essentialised notions of specific cultures can be leveraged by the far-right.

g tools as we re-think our approach to teaching language, culture, and history. Derek Duncan & Jenny Burns’ presentation on Thematic Cartographies: Transnational Modern Languages and Cecilia Piantanida’s Hybridity and Transnationalism in the Modern Language Class suggested ways of challenging student preconceptions of cultures and nations by adopting a transnational and decolonising approach to teaching, thinking through how idealised and essentialised notions of specific cultures can be leveraged by the far-right.

The symposium was a valuable source of inspiration, exchange and connection. The conversations begun on the day will no doubt develop and evolve in fruitful ways. We would like to thank all contributors, including our excellent presenters and colleagues who participated in the rich discussions. We would also like to thank the IMLR and UCML for their support in bringing the symposium into being. We are keen to use this as a starting point for further work on the way in which transnationalising and decolonising approaches can further enhance our teaching, and look forward to talking, listening, and learning more.

Dr Marcela Andrea Cazzoli, (Durham) Associate Professor (Teaching) / Director of UG Education

Dr Elizabeth Wren-Owens (Cardiff), Director of Postgraduate Research and Deputy Head of School