Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Stories from the Exile Archives: German-Czech refugee Herbert Löwit remembered on VE Day

To mark the 75th anniversary of VE Day, Clare George highlights a story from the IMLR archives of the young Czech-German refugee Herbert Löwit, and his role in the surrender of power to the Allied Forces at the end of the Siege of Dunkirk in May 1945.

When German forces finally capitulated, Löwit’s fluency in English, German and Czech was put to use when he was entrusted to act as the telephone link between the headquarters of the German troops and the Czech Independent Brigade, which had besieged the town for the Allies since October 1944.

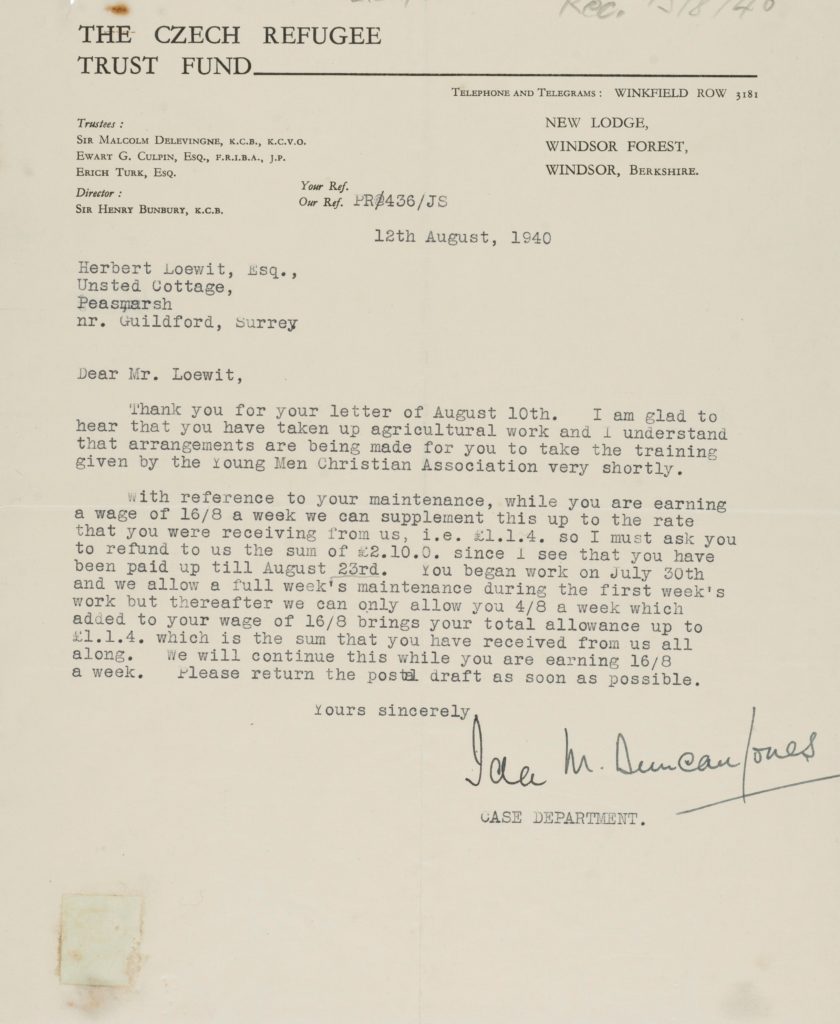

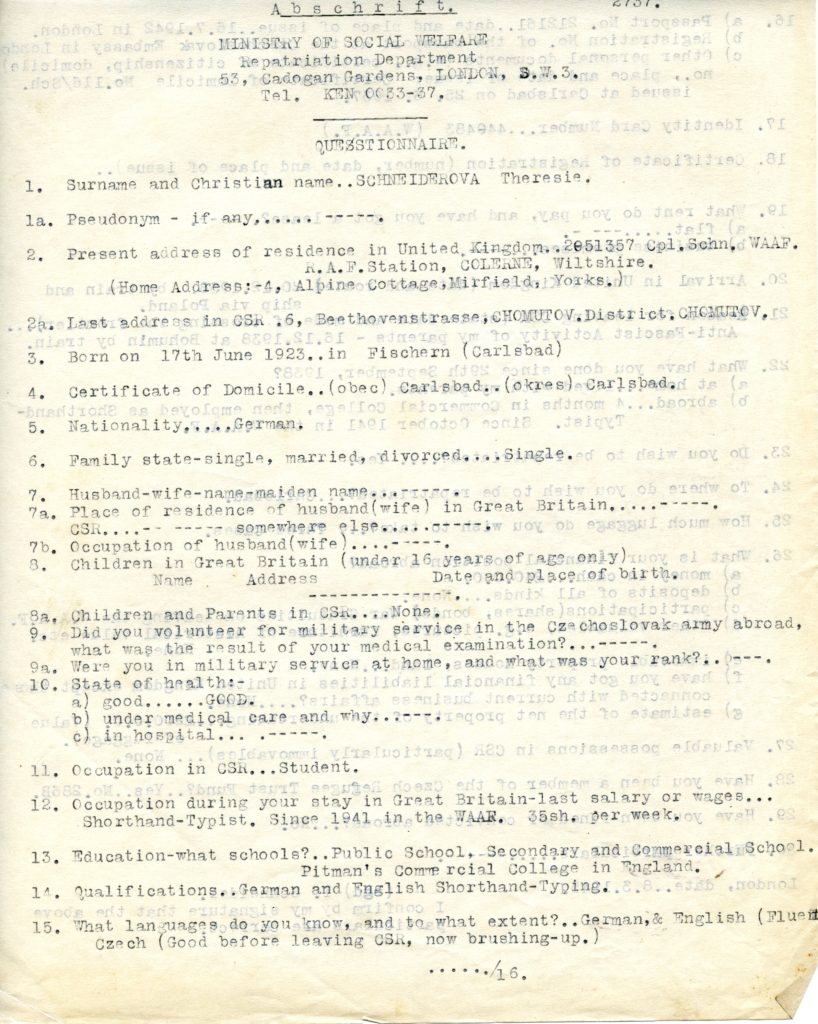

Herbert Löwit generously donated his family papers to the Institute in 2009, three years before his death in 2012. They constitute a fascinating record of the families of Löwit and his wife Theresie (née Schneider) and their experiences as refugees from German-speaking Czechoslovakia in the late 1930s and 1940s. The trade unionist activities of Löwit’s father-in-law, Joseph Schneider, supporting his comrades in exile, are particularly well documented, but there are also records of the more personal aspects of exile life. These include exchanges with the Czech Refugee Trust Fund concerning Löwit’s maintenance and employment before he joined the Czech Independent Brigade on his 18th birthday in May 1941, and questionnaires completed by family members towards the end of the war as part of the repatriation process.

Earlier this year we were delighted that an oral history interview carried out with Löwit in 1998 was added to the collections by Dr Tony Grenville of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies. The interview records Löwit’s reflecting back over the path of his life from childhood in Czechoslovakia through his experiences in the army and to life in post-war UK. It includes a fascinating account of his role as a translator for the Allies in May 1945, and we hope to make it accessible through digitisation within the coming months. We are very grateful to Dr Grenville for the donation and to Löwit’s daughter Sylvia Daintrey, for her support and for the granting of copyright.

Further information about the archive can be found here.

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR

Translating Glissant

In this blog post, Charles Forsdick – James Barrow Professor of French at Liverpool and AHRC Theme Leadership Fellow for ‘Translating Cultures’ – presents The Glissant Translation Project. This is a collaboration between Louisiana State University and Liverpool University Press that he currently co-directs with Alexandre Leupin. With the first three volumes in the series due next month and his own translation of Mémoires des Esclavages in preparation, he explores what it means to translate the Martinican author and intellectual Edouard Glissant – and also reflects, more generally, on the importance of translation in an age of confinement.

To translate – and to reflect on translation – in our current context of confinement is to sense, in often unexpected ways, the expansiveness and interconnectedness with which, as Edouard Glissant makes clear throughout his work, the practice is inevitably associated. A wide-spread perception of invisibility of the translator is to be associated with a perception of the isolation that translating is seen to demand, i.e., the complementary loneliness of the translator. Yet physical isolation does not necessarily entail cognitive seclusion. Indeed translating Glissant reminds us that the opposite is often true, not only as a result of the inherent subject matter of the author’s writings as they explore the multidirectional, dynamic interrelations of the ‘Tout-Monde’ [Whole-World], but also because of the work that translation requires. Translation depends on research, of course, but is also a form of research in its own right. The translator is obliged to connect with the multiple contexts – historical, social, cultural, intellectual – in which the writer and thinker operated. Also, Glissant’s thought was elaborated over an interconnected series of texts produced across six decades. It contains a recurrent critical lexicon, necessitating dialogues – implicit and explicit – with others who have translated his work, among whom are some of the finest critics of his work. And at the same time, to translate Glissant is to be drawn into his own complex reflection on translation – and to seek to emulate that in your own practice. In a recent review of Nathanaël’s 2020 translation of Sun of Consciousness, Matt Reeck notes: ‘Every translation brings forth a new book that bears a relation to other books: either other translations of the same source-language text, other translations of other books by the same author, or books with some other imminent, volcanic relation. At the same time, each translation redefines the entire set through the new possibilities that it brings.’

By elaborating, across several of his later works, the concept of the ‘Tout-Monde’, Glissant consolidated his reputation as one of the key thinkers of globalization at the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In her 2011 obituary of the author, Celia Britton has defined ‘Tout-Monde’ as ‘a view of the whole world as a network of interacting communities whose contacts result in constantly changing cultural formations’. The idea represents in this way the culmination of Glissant’s lifelong reflection on the ways in which cultures interrelate and then navigate these interrelations with a range of strategies that amplify or mitigate the power dynamics embedded within them. Glissant is, however, one of those authors who tends to be cited more than he is read – and cited selectively in ways that flatten the richness and complexity of his writings. The influence of his work in fields such as postcolonial studies and world literature is well-established, but an impact is now increasingly apparent in other areas such as cultural and visual studies. At a time when we are impelled to reflect on the links between the individual and the social, the local and the global, the isolated and the interconnected, being able to read Glissant seems more urgent than ever.

For anglophone readers, translations of his work are readily available. These tend to privilege his essayistic writing over his ‘creative’ work (poetry, novels, theatre), although in Glissant’s oeuvre that distinction is largely redundant. La Lézarde [The Ripening], the Renaudot-winning novel that thrust the author into the critical limelight in 1958, has benefited from two translations – by Frances Frenaye in 1959, and J. Michael Dash in 1985. Another of Glissant’s eight works of fiction, Le Quatrième siècle [The Fourth Century], was translated by Betsy Wing in 2001. English versions exist also of his collected poetry (produced by Jeff Humphreys in 2005; earlier translations exist of Les Indes [The Indies] and Le Sel noir [Black Salt]) and of the remarkable play Monsieur Toussaint, based on the final days of the leader of the Haitian Revolution (again translated twice, by Joseph G. Foster and Barbara A. Franklin in 1981, and then by J. Michael Dash in 2005).

More influential, however, has been Le Discours antillais, a collection of essays published in 1980 containing work written following Glissant’s return to Martinique in 1965 (he had been banned from travelling by de Gaulle in 1959, the year he co-founded the Front Antillo-Guyanais to campaign for the independence of the French DOM-TOMs). Parts of this book were translated by J. Michael Dash in 1989 as Caribbean Discourse, a volume which, along with Faulkner Mississippi (a reflection on opacity and cultural interconnectedness of what Martin Munro dub the ‘American Creoles’ that link the Francophone Caribbean and the American South) remains free-standing in the author’swider oeuvre. These books do not belong to the core cycle of Glissant’s writing, the five volumes of his Poétique [Poetics], of which the first three are available in English-language versions: Poetics of Relation was translated by Betsy Wing in 1997, followed by Poetic Intention and Sun of Consciousness (both translated by Nathanaël and published by the excellent Nightboat Books in 2010 and 2020 respectively).

At first glance, this appears to be an impressive corpus of material circulating in English translation, although on closer inspection it becomes apparent that all these works (with the exception of Faulkner, Mississippi, from 1996) were first published in French before 1990. They fail to represent as a result the thinking I have associated elsewhere – following Edward Said’s reflections on ‘late style’ – with the ‘late Glissant’. The last two decades of Glissant’s life, straddling the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, are characterized by a remarkably rich corpus of critical and theoretical writings. There was one final novel, Ormerod (2003), but Glissant’s energies were otherwise concentrated on a series of seventeen essays, books of interviews, manifestos and anthologies that reflected the conclusion of a lifetime’s reflection on questions of culture, language, memory, history – and the creation of knowledge in and about the Caribbean and beyond.

The three translated texts gathered loosely under the generic label of the essay – Soleil de Conscience, L’Intention poétique and Le Discours antillais – contain in embryo the strands of the author’s later thinking on poetics, diversity and relation, but it was in works published in his final twenty years that Glissant’s intellectual contribution would be broadened, deepened and amplified, reaching wider audiences on both sides of the Atlantic and elsewhere. This flourishing of activity can be mapped closely onto a major shift in Glissant’s career, his move to Louisiana State University as Distinguished Professor in 1988, followed by his taking up a final post of Professor of French Literature in the Graduate Center at City University of New York in 1994. This period in the USA was one of intense activity, including for instance a collaboration with Jacques Derrida, Salman Rushdie and Pierre Bourdieu in the establishment of the International Parliament of Writers in 1993. At the same time, his international visibility was in the ascendant, with a number of colloquia devoted to his work and nominations for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Glissant Translation Project, launched at Louisiana State University, is an attempt to present to wider audiences the rich and complex thought evident in works from these final two decades of the author’s life. In collaboration with Liverpool University Press, the initiative is committed to making these writings available for the first time in English translation. The first three books are scheduled for June 2020: The Baton Rouge Interviews, translated by Kate Cooper, is a collection of conversations from 2008 that captures the core strands of Glissant’s thought on language and poetic engagement, and reveals the breadth of reference on which he drew in his reflections on decolonization, creolization and the task of the writer; secondly, Introduction to a Poetics of Diversity, translated by Celia Britton, is made up of four lectures, followed by discussions and six interviews with Lise Gauvin – it covers a similarly wide range of subjects, but recurring themes are creolization, language and langage, culture and identity, monolingualism, migration and the ‘Chaos-world’; and then finally, Treatise on the Whole-World, again translated by Celia Britton, analyses the contemporary world, fashioned by globalization, migration and the afterlives of colonial empire, understood as a multiplicity of different communities interacting and evolving together. Across all three texts, Glissant argues against all attempts, political and philosophical, to impose universal or absolute values, and argues instead for the existence of the ‘Whole-World’, unpredictable, chaotic, creolized, in which identities are neither fixed nor self-sufficient but formed in ‘Relation’ to each other. The aim of these translated volumes – and the others that will follow – is to challenge received ideas about Glissant’s thinking (in part generated and perpetuated by the relatively limited range of translated titles in circulation) and to extend understanding of the importance of his work among English-language readers across a wider range of disciplines and sectors.

As part of this project, I am currently preparing the translation of Glissant’s Mémoires des esclavages [Memories of Enslavements]. The text began as a 2007 report, commissioned by then French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin, on the establishment of a ‘Centre national pour la mémoire des esclavages et de leurs abolitions’. This is nevertheless a deeply poetic text, resonating with its author’s other writings, in which practical recommendations relating to archives and institutions are juxtaposed with reflections on the recovery and revalidation of the painful memories of the black Atlantic. As I grapple with Glissant’s labyrinthine syntax, with his semantic experimentation and resort to neologism, I try to imagine a new (anglophone) readership for this text amongst those activists and scholars committed to the urgent memory work linked to transatlantic slavery and its afterlives. Mémoires des esclavages emerged from a distinctively French and Francophone context, but its content has more general applicability for wider debates in this area. As such, I find myself reflecting increasingly on the potentially reparative functions of translation itself: its commitment to the purposeful circulation of new knowledge and ideas both in unanticipated contexts and to new practical ends. Such an approach is implicit in Glissant’s own thinking on translation, which he understands as a creative relating and activating of linguistic and cultural systems initially and superficially seen as distinctive. In The Baton Rouge Interviews, Glissant notes that translation is ‘one of the most important arts of the future’, a nexus of imagination, creolization and unpredictability. ‘Translation is therefore’, he concludes, ‘one of the most important kinds of a new archipelagic thinking. It is an art of the flight’ – un art de la fugue.

Charles Forsdick, James Barrow Professor of French at the University of Liverpool and AHRC Theme Leadership Fellow for ‘Translating Cultures’

‘What are you reading?’ José Lezama Lima: the immobile traveller for immobile travellers, from William Rowlandson

‘Platicamos ya de mi calma móvil, de mi inmóvil trasiego, de mi ansiedad sedente’ (Let’s talk about my mobile stillness, my immobile activity, my sedentary restlessness)[i]

Plans during lockdown remain mostly unfulfilled. I’ve not shone with creativity. I’ve not read any Galdós (not that I’d planned to). I’ve not achieved mighty things. But I have read Camus’ The Plague and I have re-read José Lezama Lima’s Paradiso for the first time since dedicating four years of my life two decades ago to obsessive scrutiny of the novel for my PhD.

What tremendous comfort. What an experience.

Lezama was maestro of a dynamic group of poets, painters and a priest in 1940s and 50s Havana dedicated to artistic, poetic and spiritual exploration. A mystery school of sorts. Whilst proudly Cuban, their shared vision of culture was americana (which in Spanish means of all the Americas) and global. No image or culture was beyond their poetic reach. The aesthetic richness was also political. The poets and painters of Orígenes puzzled over what it meant to be Cuban, to be inspired by the poet-statesman José Martí, to resist the deadening impact of commercialism and corporatism and foreign dominance of economy and culture, to sing of Cuban identity as an identity. Their visions were inspiring. They were revolutionary.

Lezama rejected the corruption, venality, injustice and aggression of both Machado’s and Batista’s dictatorships. He was as conscious as Castro of the need to carry to conclusion the revolutionary project initiated in the nineteenth century wars against Spain and emblematised in Martí. Lezama’s was a revolution of art, and he threw his considerable energies into projects for the promotion of literature in Castro’s new order, becoming Director of Literature and Publications of the National Council of Culture, and later one of the vice presidents of the UNEAC, the Writers and Artists Union. No poet, painter or novelist in Havana would not have known of Lezama. Most were friends. Yet by the mid-60s the Orígenes group had disbanded and solitary figures were pushed into exile or silence.

Lezama’s vision of history was of the people’s capacity for creative expression. He saw culture as a process of transformation, expansion, exploration, integration, inclusion, interchange. Cultures are enriched by other cultures. Any culture failing to be enriched by other cultures will fail to enrich other cultures. This vision is articulated in his poetic essays of La expresión Americana (1957) and La Cantidad Hechizada ([1970], which include Las Eras Imaginarias). Lezama was deeply stirred by the need for change, but his revolution is aesthetic, poetic, spiritual, and often at odds with the political transformations happening around him. Paradiso was well received until news of the explicit scenes of sex, some gay, all gothic and macabre, reached the censors. An integrally Cuban novel, there was nothing overtly political, and a non-political book is political by being non-political. Nothing about the glories of the revolution, the depravity of Batista, the poverty of Cuba under imperialism. In fact, the story is about an asthmatic bourgeois kid from a military family living in one of the big houses on the Paseo del Prado. And his poetry continued to be baffling – blooms of odd words in odd syntax. No socialist hymns here. No stirring praise of Che’s New Man. No eulogy for collectivization. Paradiso cannot even be called elitist; it is baffling for everyone.

He penned a eulogy to Che Guevara after his death in Bolivia, ennobling him as a mythic hero, brother of Tupac Amaru, protected by Viracocha. Stirring stuff. But the text is weird (and very hard to translate.): ‘Girdled by the ultimate test, bare stone of the beginnings to hear the inauguration of the word, Death went looking for him.’ And it continues, in typically lezamiano strangeness: ‘Like Anfiareo, death does not interrupt his memories. At the moment of crisis, when necks are exposed, he was always protected by aristía, protection in combat, but also areteia, sacrifice, the zeal for holocaust. He sacrificed himself on the funeral pyramid, having undergone the terrible ordeals of his power for transfiguration.’[ii] And I’ve selected the simplest bits of this bizarre piece. I have often wondered whether there was mockery in his praise; perhaps not mockery of Guevara but of the official hero-worship. But then again, the language in this piece is no different from any of his other texts. Nothing is simple with Lezama.

His ostracism and his asthma increased with his international reputation. He was removed from official posts. His sister fled to Florida. Lezama died in 1976, his second novel, Oppiano Licario unfinished, out of favour by all but his close friends, hungry, thinner and sad.

Yet his star has risen over the last two decades, notable with the republication of much of his work, and the conversion of his house into the Casa-Museo Lezama.

‘I live on Trocadero, a narrow, hot and dusty street’, explained Lezama in an interview with Felix Guerra.[iii] Trocadero is indeed a dusty furnace. Your eyes water. The walls glare in the sun. It makes you thirsty. ‘I would give another eternity to have a tree in front of my house,’ he said. ‘So great is my longing that I would move house – I would abandon my house – just to have the one tree. I would live happily in a branch, if the sparrow made room for me.’ The casa-museo is blissfully cool inside, with cracked patterned tiles on the floor and open doors leading off a small patio. But there is no tree to be seen, not until you leave the house and strain your eyes to the end of the street where it joins the leafy boulevard of Prado, where Lezama used to stroll.

Cuba, like the British Isles, is an archipelago of trees. And like here, many of the old forests are lost. Lezama felt that loss personally: he used to pee against trees as a kid and he would have continued to do so, but ‘carezco de árbol íntimo (I lack an intimate tree).’ No tree in his patio. He felt that loss nationally: Columbus’s vision of wooded paradise, he says, is no more. He also felt it globally, and reflected sadly on the slaughter of trees in the Amazon: ‘When man swings his axe,’ he declared prophetically, ‘he swings it against his own neck. The man’s blood and mine flow in the mortal neck of the tree, and the tree will not survive this crime against itself.’[iv] And so quickly are the trees lost, he muses, that he will never find that tree in whose branches he might live. What an image: forest-felling as an act of suicide. How prescient. And these words are from over forty years ago, before the language of ecosystem collapse and climate change was so pervasive and so pressing.

He wrote strange poems. All his writing is strange. Voluptuous vine-creeping sentences of bizarre words, adjectives made from nouns and adverbs made from people’s names. Bedazzling landscapes filled with creatures, demons, monsters and erotic vegetation. Macabre and sinister sexual encounters. Arcane numima from archaic cultures. His art is often described as ‘baroque’, which captures something of its quality, but even the baroque is too static. I imagine Lezama sitting, hot and fat and asthmatic, daubing at his thin moustache with a white handkerchief, clutching his soggy cigar between chubby fingers, and planting dream-forests, word-woodland, jungle-visions. He wrote his own intimate trees.

‘Each tree,’ he wrote, ‘is a cathedral of leaves and each leaf a cathedral of seasons.’ How beautiful. How sad that he lacked his intimate tree. And yet his poetry compensated for this lack . He called himself, like the tree, un viajero inmóvil, a stationary traveller, ‘hasty to be still, to be serene beneath the moving sky.’[v] He scarcely left his house, scarcely left Havana, and left Cuba on three brief occasions.

‘Travel is little more than a movement of the imagination,’ he wrote. ‘Travel is to recognize, recognize oneself, it is the loss of childhood and the admission of maturity. Goethe and Proust, those men of great diversity, almost never traveled. Their ship was the imago. I am the same; I have almost never left Havana. I acknowledge two reasons: each time I left, my bronchial tubes got worse; in addition, the memory of my father’s death has floated at the center of every trip. Gide said that every voyage is a foretaste of death, an anticipation of the end. I don’t travel: that’s why I return to life.’[vi]

Lezama has been a great comfort over the past twenty years. He has been a great comfort over the last month during isolation. ‘No hay nada más real que la imaginación.’ Bodies are not essential for travel. Journeys are not measured only in miles. Dreams, visions, poetry and the imagination sustain us. And those of us lucky enough to have trees visible from our windows are blessed.

Good health to the trees. Good health to Lezama. Good health to all.

Dr William Rowlandson, Senior Lecturer in Hispanic Studies at the University of Kent

[i] ‘Para leer debajo de un sicomoro. Diálogo casi interminable con José Lezama Lima’ Por Félix Guerra – 17/11/2017 https://www.fronterad.com/para-leer-debajo-de-un-sicomoro-dialogo-casi-interminable-con-jose-lezama-lima/ (translation mine).

[ii] Lezama Lima, José (1988) Muerte de Narciso: antología poética, ed. David Huerta (Mexico City, Ediciones Era), 133.

[iii] Guerra

[iv] Guerra

[v] Guerra

[vi] Lezama Lima, José (2005) José Lezama Lima: Selections, ed. and trans Ernesto Livon-Grosman (University of California Press): 175.

The Making of ‘Urban Microcosms 1789-1940’. A conversation among co-editors Margit Dirscherl and Astrid Köhler

In the times of COVID-19, one of the many small but crucial things we miss is the opportunity for casual conversation among colleagues, be it at conferences, research seminars, or lunch breaks at work. In light of the current situation, which puts us and other colleagues in the UK and elsewhere in our home offices, we would like to share a conversation about our co-edited volume Urban Microcosms 1789-1940, which is the latest publication in the series imlr books.

Margit: Astrid, I remember that our project began, as so often, with a chat among colleagues, the kind of thing we miss these days. We spoke about our new research projects, and we knew they had quite a bit in common, although in the beginning we could not fully pin down what it was. You have an interest in spa towns, I have an interest in railway stations. Both our topics focused on European literary and cultural history of the 19th century – but that couldn’t be it.

Astrid: No, it wasn’t. And the proximity of spas to stations didn’t really matter either. Instead, both spas and stations appeared to be special places for modern societies: central to urban life, yet sticking out of its fabric, neither closed off from it nor entirely part of it, both principally open to everyone, yet each including a number of semi-public and even private spaces. In the conversations that followed, it also emerged that we both needed to venture beyond our disciplinary comfort-zones in similar ways. We each explored urban studies and cultural sociology, such as by Richard Sennett, Anthony Giddens and Michel Foucault, with the inevitable nod towards the ‘spatial turn’ in the Humanities. This may have been the reason why it seemed natural to collaborate in some way or other. And it did not take long to find the term that focalised our topics: Urban Microcosms.

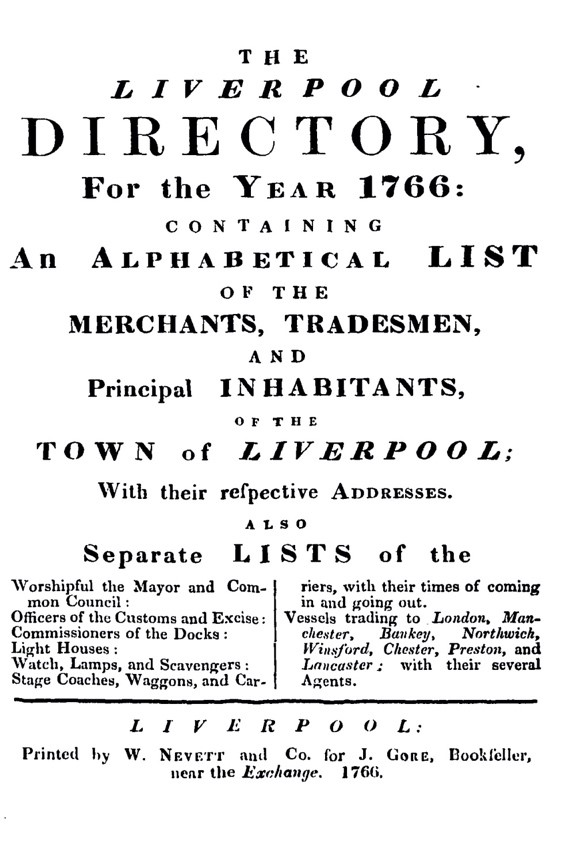

M: I recall you were the one who came up with this term. Once we had found it, everything else fell into place. We would, with the help of our literary texts and various other artefacts, put city life under a magnifying class, and we would invite others to join us in this endeavour. When we received the responses to our CFP, we could compile an inspiring conference programme that featured a wide variety of microcosms, including phenomena that structured city life, such as the radio, the sound of church bells, town directories, and of course the fascinating Belgian ‘road conferences’. Other papers addressed public and private parks, harbours, department stores, cafés, restaurants, and seaside resorts – although the latter are, like the spas you work on yourself, not located in cities!

A: They do, however, feature urban qualities. Of course, working on this new concept was challenging in a number of ways. Colleagues from across the humanities and the social sciences had written to us, and approached their respective ‘microcosms’ in different ways. This is why, when our conference guests arrived, we still weren’t sure whether we would find a solid enough common ground for discussion. After all, it was our aim not only to bring our ideas together, but to work on the shared concept of the ‘urban microcosm’.

M: Eventually, it wasn’t just this core concept we kept addressing, but there were also certain motifs that re-emerged, such as objects which seem to be core-accessories of urban life, like the parasol, at least in the 19th century, or rules and rituals, like the expectation to preserve silence in a museum. In terms of finding common ground, sociological concepts proved to be useful. For example, Richard Sennett’s seemingly simple yet illuminating definition of a city as a place where ‘strangers are likely to meet’ applies to the majority of our ‘microcosms’, in different yet comparable ways.

A: It was also from our conference discussions that the plans for the book and its subsequent structure emerged. Dividing the microcosms into exterior and interior places seemed straightforward – until we debated to what extent a railway station is an interior and/or an exterior place. We subsumed those microcosms where the relationship between place and space proved rather elusive – such as church bells and radio waves – under the heading ‘discursive spaces’, and finally we devised a separate category for those which are located outside the towns and cities altogether while insisting that they, too, are part of the networks of interconnected nodes spanning city, town and country.

M: Another challenging task was to produce a cover that was commensurate with the contents. Inspired by Paul Klee’s painting “Hauptweg und Nebenwege” (1929), we came up with a design which represents a unity and shimmers a little like a floodlit city, but which, when looked at more closely, is made up of networks of smaller units that relate to each other in a number of ways: colour, shape, proximity, harmony, antagonism. Sometimes paths emerged between these blocks, others came together to form larger structures, others again answered each other across the whole. And at the edges it was always uncertain whether and how far these patterns could continue into the unknown white space beyond. We were lucky to find an artist who exactly understood what we were aiming for.

A: Despite the wide spectrum of urban microcosms explored in the book, we are very aware that their potential number is almost inexhaustible: just think of market squares, river banks or cemeteries, theatres, hotels or brothels, the stairwells in large apartment buildings or indeed the public toilets or urinals! But we hope to have enriched the discourse with a term that is fruitful in that it opens up space for further research.

Margit Dirscherl, Lecturer in German at St Hugh’s, University of Oxford, and Astrid Köhler, Professor of German Literature and Comparative Cultural Studies at Queen Mary University of London

Urban Microcosms 1789-1940, ed. by Margit Dirscherl and Astrid Köhler, 320 pp.

El Zapatero en la Pandemia | The Cobbler in the Pandemic. A short story by Otoniel Romero Gómez

Por Otoniel Romero Gómez, artista colombiano y profesional de la ARN Colombia

Esta mañana un hombre de 80 años que pasaba todos los días frente a mi casa despertando al barrio con un grito quebrado pero sonoro ¡¡zapatoos!! ¡¡zapatoos!!! – en su carreta de madera lleva su taller para arreglar zapatos – volvió a pasar. Hace ocho días no se le escuchaba, desde el día que se anunció la orden de confinamiento en nuestras casas. Está mañana al volverlo a escuchar creí que todo ya había pasado. Sin embargo, esta danza macabra apenas está por empezar. Salí corriendo y guardando distancia, lo llame con afán y angustia , y le dije , casi suplicando, que se estaba poniendo en peligro, que se fuera a guardar, que por su edad y lo mortal del virus con los adultos, se estaba arriesgando a ser contagiado. Y levantando sus ojos azules y cansados, y mirándome con cierta concideración, me contestó: “Hijo, hace ocho días no recibo un centavo, no tengo ni para un pan, lo único que recibo me llega por el arreglo de algún zapato en mi cotidiano deambular por las calles de esta parte de la ciudad. Hace ocho días estoy haciendo caso, me estaba comportando como un buen ciudadano, pero hace ocho días que no recibo ni un centavo, la ayuda de la alcaldía no llega.” Y mirando hacia la calle vacía y dejando caer su cabeza canosa y bronceada, exclama como si pensara en voz alta: “¡¡¡No puedo esperar más!!! O me muero de hambre o me muero por el virus, no tengo ninguna otra opción. Por eso decidí volver a la calle, porqué el hambre no deja dormir. Se es buen ciudadano si se tiene la barriga llena; con hambre la vida es una illusion. ¿Qué puedo hacer?” El viejo se acomoda nuevamente la carreta sobre sus cansados hombros mientras se anuncia por los noticieros del medio día que habrá cárcel y multas para los malos ciudadanos que rompan con la cuarentena. ¿Que irá a pasar con este viejo de 80 años, que se marchó gritando, con rabia e impotencia, y que hoy en plena pandemia sale punzado por el hambre a jugar a la ruleta rusa gritando, “¡¡¡Zapatos!!! ¡¡¡Zapatos!!!” ?

The Cobbler in the Pandemic

By Otoniel Romero Gómez, Colombian artist working for a peace process programme

Translated by Alison Menezes, University of Warwick

This morning I saw again an eighty-year-old man who used to pass by my house every day, waking up the entire neighbourhood shouting in his sonorous but broken voice, ‘Shoes! Shoes!” In a little wooden cart he brings tools for mending shoes. He hadn’t been heard for the past week, since the order to stay at home had been given. This morning, on hearing him again, I believed for a moment that everything was over. And yet this macabre dance we’re living through has only just begun. I ran out and, keeping my distance, called him over urgently, anxiously. I almost pleaded with him that he was putting himself in danger, that he should go home. That because of his age and the mortal threat of the virus he was risking infection. He raised his tired, blue eyes, and looked at me with some consideration. Then he replied, ‘Son, for the past week I’ve not received a cent, I’ve nothing to buy bread with. The only money I get is by mending shoes during my daily wanderings around the city. For the past week, I’ve paid attention, I’ve behaved like a good citizen. But for the past week, I’ve not earned a cent, and the money from the Mayor’s Office isn’t enough.’ Looking out at the empty street and letting his grey and bronzed head fall, he exclaimed as if thinking out loud: ‘I can’t do it anymore! Either I die of hunger or I die of the virus, there’s no other option. That’s why I decided to go back onto the street, because hunger doesn’t let me sleep. Good citizens have a full belly. Hunger makes life nothing more than an illusion. What else can I do?’ The old man harnessed his cart back onto his tired shoulders. Meanwhile the daily news announces that bad citizens who beak the quarantine will be fined or imprisoned. What will happen to this eighty-year-old who walked off shouting in fury and powerlessness? Who today, in the middle of a pandemic, is forced by hunger to play Russian roulette shouting, ‘Shoes! Shoes!’

Otoniel Romero Gómez, Colombian artist working for a peace process programme