Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Stories from the Exile Archives: Internment and the Berger Family

The internment of nearly 30,000 so-called enemy aliens in May and June 1940 not only deprived those imprisoned of their liberty. It also broke up families already torn apart by exile, disrupted much-needed social networks and, in many cases, left dependants without support. In the second of a series of blogs commemorating the mass internment of refugees from Nazi Germany and Austria, Miller Archivist Clare George looks at what the archive of Austrian refugee artist Margarete Berger-Hamerschlag tells us about the impact on the family of the internment of her husband, Josef Berger.

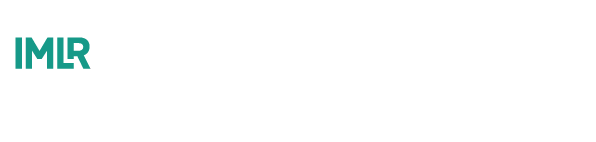

In 1920s Vienna, both Berger Hamerschlag and her husband had begun to establish themselves in their respective professional fields, she as artist and designer and he as architect and interior designer. By the 1930s however, work was becoming hard to find in impoverished Austria, and after the establishment of the Austrofascist regime, the couple emigrated. They spent two years in Palestine before settling in London in 1936, where their son Florian was born in 1937. In her artwork Berger-Hamerschlag reflected on her growing emotional attachment to the UK at this time.

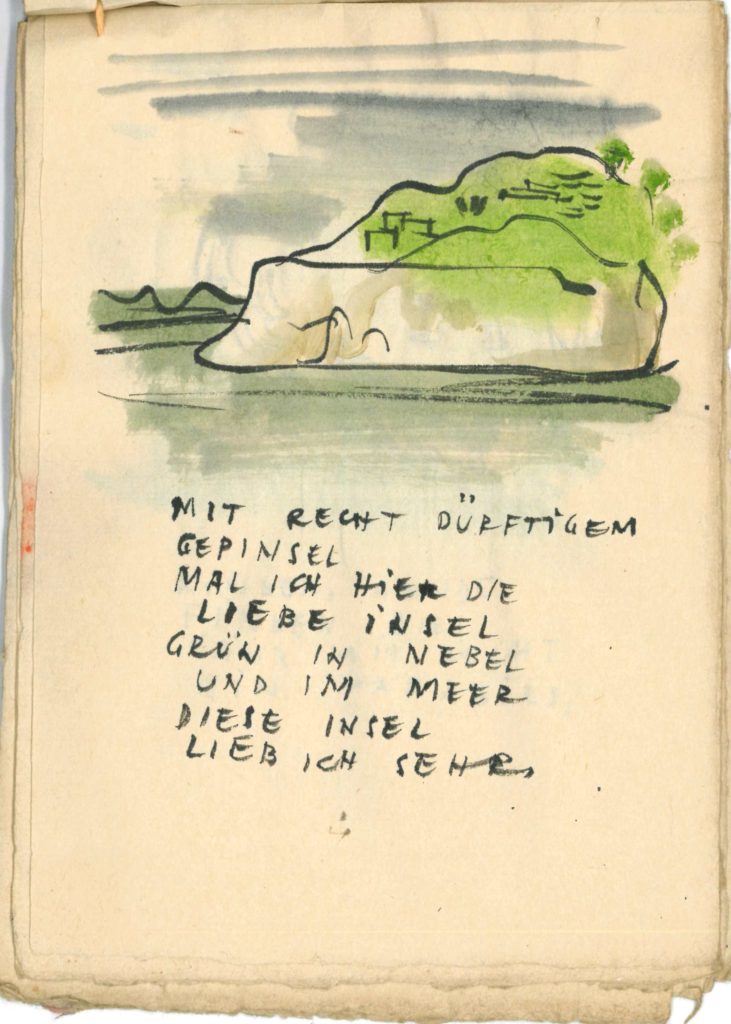

Their hope of returning to Austria disappeared with the Anschluss in 1938 and they focused on rebuilding their careers, making new friends and supporting other exiles in the UK. In the short time between arriving in the UK and the start of the war, Berger-Hamerschlag sold paintings, designed clothes for Elisabeth Bergner, Molly Fordham and the News Chronicle and had her work displayed at several international exhibitions, including the Unity of artists for peace, democracy, and cultural development in 1937. Her financial position remained insecure however, and she was dependent on her husband Berger, who achieved some success in architectural competitions.

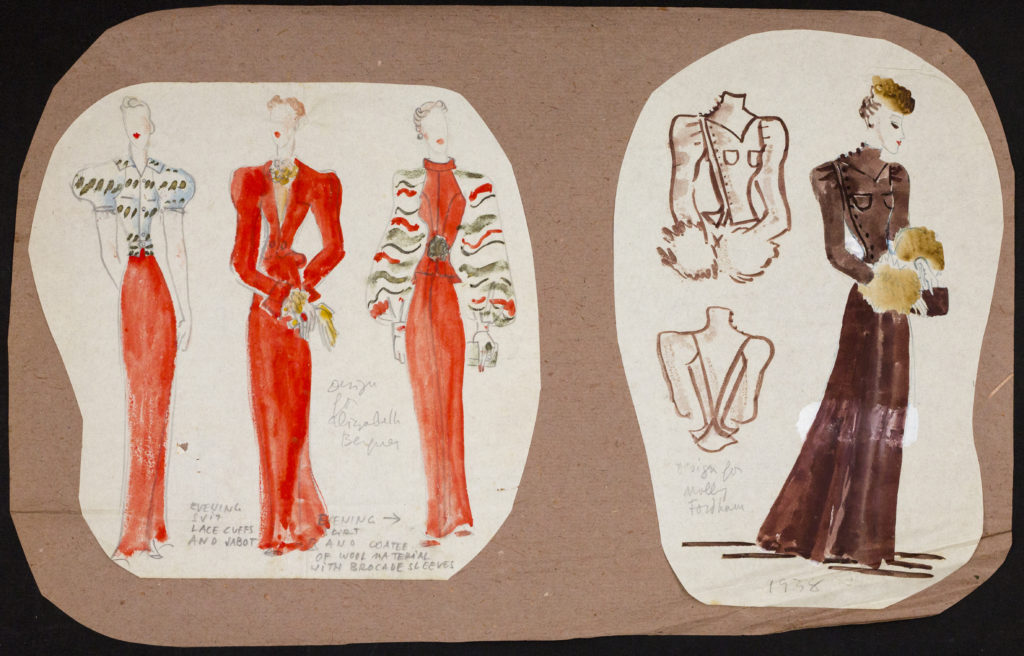

On the outbreak of war, Berger was called to attend an ‘Enemy Alien’ tribunal where, like 55,000 others, he was assessed as a Category C (no security risk) and exempted from internment, as his Home Office record at The National Archives shows. Eight months later, however, with rising anti-alien hysteria whipped up by the press and the decision to ‘collar the lot’, Berger was deemed a threat to national security after all and interned along with around 27,000 other Germans and Austrians.

The trials and hardships Berger-Hamerschlag went through whilst her husband was interned are documented in the hundreds of pages of letters Berger-Hamerschlag wrote to her husband at this time. The pain of their separation at such a difficult time was made worse by the dismal postal communications between the camp and the outside world. Three weeks after his arrest she had still received no word from him, as she complained in a letter to the censor of Mooragh Camp, Isle of Man, where he was being held. The postal system improved only slightly little over the following months.

The highlight of the letters for Berger were probably the updates on three-year-old Florian, whose interest in drawing and art was growing, stimulated perhaps by the stories and illustrations Berger-Hamerschlag created for him. The letters also gave news of refugee friends. On 7 September, for example, Berger-Hamerschlag reported joyfully that she had seen her brother-in-law Fritz Lampl, who had just been released from internment. However, much of what she wrote must have concerned Berger greatly. Payments she had relied on from the Unemployment Assistance Board had stopped while Berger was interned, and she was surviving on a bare minimum of food. Berger had to write to the UAB from Mooragh Camp to ask for more support for his wife and request that they be reinstated urgently. A letter a few weeks later confirmed that she would now receiving the grand sum of 25 shillings a week (less than £50 in today’s money) to pay the rent and buy food for herself and their child.

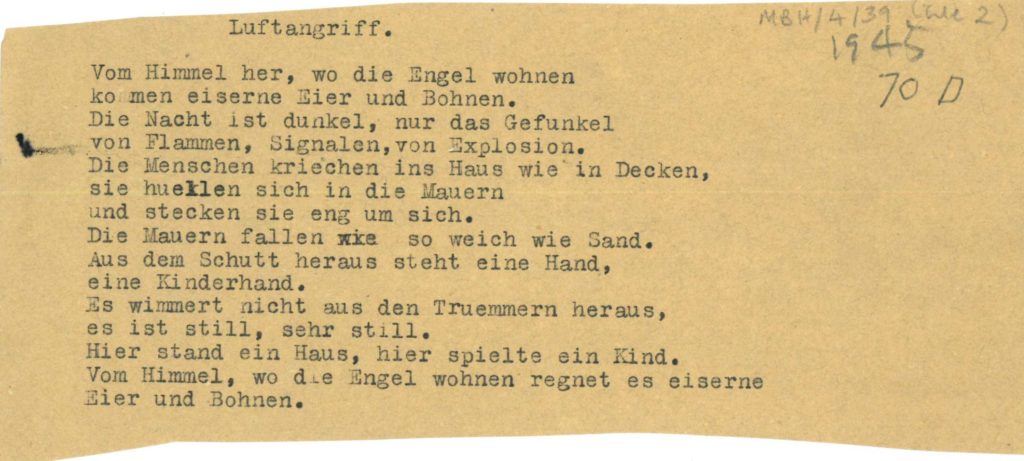

Another cause of anguish was the Blitz, which began two months after Berger’s internment and was accompanied by fears of a German invasion. Anti-German sentiment was running high, and Berger-Hamerschlag’s British neighbours clearly had little understanding of the difference between the German enemy they read about in the newspapers and the Austrian refugees in their midst, a letter from 14 September 1940 suggests. A week later, she and Florian faced a still worse when a bomb hit their house. They both survived but were now homeless, dependent entirely on friends and charity. Berger-Hamerschlag later reflected on the trauma of the Blitz in an unpublished poem ‘Luftangriff’.

The ordeal caused by the family’s separation came to an end only in late December 1940, when Berger was released after an appeal by a number of prominent figures in British art and architecture including Scottish artist, Sir Muirhead Bone, who was then on the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, his son the artist Stephen Bone, the art critic Eric Newton, and RBA Fellow Professor Charles H. Reilly. Soon after his release Berger was employed by London County Council to work on post-war town planning under Sir Patrick Abercrombie, and after the war the couple remained in the UK and gained citizenship. The publication of Berger-Hamerschlag’s book Journey into a Fog, recounting her experiences of teaching art in deprived London youth clubs in the 1950s, finally brought Berger-Hamerschlag financial independence in 1955. She had little time to enjoy this success, however, as she sadly died of cancer in 1958.

Berger-Hamerschlag’s papers were donated to the IMLR in 2010 and are now managed by Senate House Library on behalf of the Institute. Dr Anna Nyburg of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies carried out the initial sorting of the material and we are grateful to her research which has helped with interpreting some of the records. Further information about the archive can be found here and an online catalogue of the archive can be found here.

Read more Stories from the Exile Archives

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR.

Female Agency & Inner Thoughts in the First French Translation of Doris Lessing’s ‘Martha Quest’

Dr Mélina Delmas finished her PhD in Translation Studies at the University of Birmingham in April 2020. Her thesis, which is entitled “(S)mothered in Translation? (Re)translating the Female Bildungsroman in the Twentieth Century in English and French”, brings together Translation Studies, Gender Studies, the Sociology of Translation, and Reception Studies.

Martha Quest (1952) is Doris Lessing’s second novel after The Grass is Singing (1950) and the first opus of the Children of Violence series (1952-1969). This first volume follows the eponymous character during her adolescence on an African farm, and then in the big city where she takes on a job as a secretary while exploring the pleasure of parties and the attention of male suitors. Martha Quest was first translated into French in 1957 by Doussia Ergaz and Florence Cravoisier.

Martha Quest has been described as a coming-of-age story or Bildungsroman. If the Bildungsroman has traditionally been a male-focused genre, the nineteenth century notably saw the emergence of a female Bildungsroman. But, “gender often clashes with genre” (Marrone, 2000, p. 16) and, as social norms were dramatically different for men and women at the time, these ‘Bildungsromane’ were very different from their counterparts written by male writers about male protagonists. Whereas in the male Bildungsroman, the pattern of the life of the main character is said to be spiralling upward, the pattern of the female Bildungsroman is usually circular as the protagonist’s fate ultimately still leads her to walk in her mother’s footsteps and to become a wife and mother herself. However, the twentieth-century saw the rise of “a number of feminist Bildungsromane which more closely approximate the male model of the Bildungsroman in their delineation of the education, reassessment, rebellion, and departure of their respective female protagonist” (Goodman, 1983, p. 30). Still, female Bildungsromane are usually more focused on “the heroine’s inward, vertical movement toward self-knowledge” (Marrone, 2000, p. 18).

“Flashes of Recognition”: Inner Thoughts and Agency

Because the female journey is more of an internal one, the main protagonist’s inner life is paramount to understanding her perspective. Revealing the protagonist’s inner thoughts constitutes one of the narrative techniques used by the writer to give the reader access to the rebellion buried deep within the protagonist’s psyche. Moreover, it is through the protagonist’s internal monologues that her agency is displayed. In Martha Quest, inner thoughts are central to the reader’s understanding of Martha’s Bildung and development. For Stimpson: “[s]ince the evolution of consciousness matters so much, Lessing devotes a great part of Children of Violence to Martha’s own. The narrative is a detailed, subtle account of the methodology of growth, in which Martha is a case study, an exemplary figure, and our potential representative” (1983, p. 193). However, in the first French translation of Martha Quest, many of Martha’s internal monologues are cut. For instance, one of the pivotal moments of this inner journey, in which Martha has an epiphany and realises that she needs to set herself free, that “she must leave her parents who destroyed her”, is completely omitted in translation, as can be seen in the table below.

Table 1

| Martha Quest (1952) | Martha Quest (1957) |

| She wanted to weep, an impulse she indignantly denied herself. For at that moment when she had stood before them, it was in a role which went far beyond her, Martha Quest: it was timeless, and she felt that her mother as well as her father, must hold in her mind (as she certainly cherished a vision of Martha in bridal gown and veil) another picture of an expectant maiden in white; it should have been a moment of abnegation, when she must be kissed, approved and set free. Nothing of this could Martha have put into words, or even allowed herself to feel; but now, in order to regain that freedom where she was not so much herself as a creature buoyed on something that flooded into her as a knowledge that she was moving inescapably through an ancient role, she must leave her parents who destroyed her. So she went out of the door… (90-91) | Elle éprouvait une violente envie de pleurer, mais n’aurait voulu y céder pour rien au monde. Omission Elle franchit la porte… (112) |

In this scene, Martha has an insight into what her destiny will be: stuck in a marriage with no opportunities for growth. Wearing a white dress which resembles a “bridal gown” (90), Martha is waiting on the threshold of the farm – but also symbolically on the threshold of adulthood – for her parents to give her away to the young suitor who will accompany her to her first ball. According to Abel, Hirsch, and Langland, this type of scene is central to the novel of female development, which contrary to the male Bildungsroman, often operates in “brief epiphanic moments. Since the significant changes are internal, flashes of recognition often replace the continuous unfolding of an action” (1983, p. 12). This climatic moment in Martha Quest corresponds to what Susan Rosowski calls “an awakening to limitations” (1983, p. 49), and is part of the “submerged plot [which] inscribes revolt” (Marrone, 2000, p. 18). In this particular scene, we can also observe the performance of gender as described by Judith Butler (1990). Martha realises that she is obliged to play her part, forced to perform her gender: “it was in a role which went far beyond her, Martha Quest: it was timeless” (90). Because of the omission of this scene in the French translation, this dimension disappears in the French text and Martha’s agency in her own destiny is thwarted. She does cross the threshold in the translation but, by not having her inner thoughts translated, the significance of the gesture is lost for the French readers.

Other instances depicting Martha’s agency are also erased in the 1957 French version. In the final section of the novel, Martha decides to look for a different job rather than staying a secretary. Her quest for independence includes going for a job as a journalist. She is appalled when the only thing they offer her is to write for the women’s page. This episode, which shows the restrictions imposed on women in the professional sphere at the time, is omitted in the first French translation. In fact, most of her job search is summed up in one page. Martha’s aspirations to become a writer (255-256) and her sending some pieces to newspapers which get rejected are also cut. This omission is unfortunate as Martha’s quest for a professional vocation marks an important step in the development of the character and her quest for agency. Furthermore, finding a good job would enable Martha to be financially independent. It might prevent her from completing the circular pattern by getting married. Finally, another remark on the constraints imposed by society on women at the time is omitted in the French translation. During her first party, Martha is kissed forcefully by a young man. She is understandably shocked and angry. However, the reader witnesses her internal struggle between these feelings of resentment and the social expectation that she should want to be swept off her feet by a man: “She resented this hard intrusive mouth, even while from outside – always from outside – came the other pressure, which demanded that he should simply lift her and carry her off like booty” (99). The terms “pressure”, “demand”, and “booty”, as well as the expression “from outside – always from outside” clearly indicate that this is not Martha’s own desire but actually an external constraint imposed on her. In the 1957 French translation, the “pressure” from “outside” is omitted and thus the desire to be swept off her feet is attributed to Martha: “un sentiment tout autre qui lui faisait souhaiter d’être soulevée entre les bras de Billy” (a different feeling which made her want to be swept off her feet by Billy) (123). This reduces Martha to a heroine of romance novels whose main thoughts revolve around being seduced by a man. It erases Martha’s inner struggle between her actual sense of self and societal gender expectations, while exhibiting similarities with conventional female Bildungsromane in which the romance plot is predominant. Overall, around ten per cent of the original text has been cut in the first translation of Martha Quest. By suppressing all these inner thoughts, we are left with only the “surface plot […] conform[ing] to social conventions” (Marrone, 2000, p. 18) of Martha’s path towards matrimony.

Martha’s intelligence and her revolt towards the principles of society are also erased in the translation. According to Labovitz, in the Children of Violence series, “books are sign posts along the way of the heroine’s development, and indications of her emotional as well as intellectual life” (1988, p. 160). In the translation, however, Martha’s love for literature is downplayed. If most of the scenes in which she is reading are translated, the scene in which she is reading Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau (241-242) is deleted. These writers are considered high-brow, and thus maybe not something that a teenage girl would read. Furthermore, in several instances, the original text appears to be criticising gender roles and the status of women as objects of desire. Unsurprisingly, in the 1957 translation, these passages are again omitted. For instance, at her first ball, Martha notices that the only people who seem to enjoy the party freely are the girls under sixteen. Sixteen corresponds to the age at which young girls would make their entry into society and have to start looking for a husband. According to Martha, these girls are the only guests who seem “unbound by […] invisible fetters”, which implies that she views marriage as a commodification of women. The first translation omits this implied criticism of patriarchal society. Finally, when partying with the clique of young men she aptly names the “wolves”, Martha tries to be herself instead of playing the part of the dumb girl. She starts talking to her suitor about one of the books she has read. This is met by a sigh, and the young man then proceeds to mock her in front of everybody. Clearly, this is again a critic of stereotypical gender roles in which the intellectual realm is reserved for men. By omitting this passage, the 1957 translation by Ergaz and Cravoisier removes layers of meaning embedded in the original text.

Moreover, it seems that there is a will to turn the ‘bad girl’ into a ‘good girl’ in translation. I already discussed how the cuts pertaining to Martha’s inner thoughts erase her inner rebellion and align the novel with circular Bildungsromane in which the main protagonist’s “‘end,’ both in the sense of ‘goal’ and ‘conclusion,’ is a man” (Greene, 1991, p. 12). There are also instances in which her feelings of resentment are suppressed:

Table 2

| Martha Quest (1952) | Martha Quest (1957) |

| She only felt resentful that her father was ill … (152) | Seule l’agitait, à cet instant, la crainte dans laquelle la plongeait l’état de santé de son père … (201) |

| Her resentment […] had been not so much dulled as pushed away into that part of herself she acknowledged to be the true one. (183) | Omission (223) |

| Each kiss was a small ceremony of hatred (192) | Omission (229) |

| ‘What?’ she exclaimed indignantly. She felt furious. She suppressed that too. (267) | ― Quoi ? s’écria-t-elle effarée. Omission (303) |

In the second entry of the above table, we can see that the particular part of the passage in which Martha experiences resentment is omitted. In another example, the word “resentful” (95) is attenuated in French to become “contrariée” (upset) (118). Finally, when Martha resents her father for being ill as “it might be used against her as an emotional argument”, her resentment is turned into “crainte” (fear, concern) in French, which is a completely different feeling. Martha’s resentment at her father being ill does not fit into societal expectations of the time for a girl’s proper behaviour. Worry or fear are feelings that would have been considered more acceptable. Hatred and fury are also feelings which are either omitted or attenuated in the 1957 translation (Table 2, entries 3 and 4).

All the changes discussed above make Martha appear more proper in the French translation and they decrease her agency. These are not isolated example, but an overall pattern which paints a very different portrait of Martha compared to the original. Martha Quest was retranslated into French in 1978 by Marianne Véron. In this new translation, Martha’s inner thoughts are restored, thus giving a more accurate picture of her state of mind.

Dr Mélina Delmas, University of Birmingham

Bibliography:

Abel, E., Hirsch, M. and Langland, E. (1983) The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development. Hanover, N.H.; London: University Press of New England.

Butler, J. (1990) Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

Goodman, C. (1983) ‘The Lost Brother, the Twin: Women Novelists and the Male-Female Double Bildungsroman’, NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, 17(1), pp. 28–43.

Greene, G. (1991) Changing the Story: Feminist Fiction and the Tradition. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Labovitz, E. K. (1988) The Myth of the Heroine: The Female Bildungsroman in the Twentieth Century: Dorothy Richardson, Simone de Beauvoir, Doris Lessing, Christa Wolf. New York: P. Lang.

Marrone, C. (2000) Female Journeys: Autobiographical Expressions by French and Italian Women. Wesport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Rosowski, S. (1983) ‘The Novel of Awakening’, in Abel, E., Hirsch, M., and Langland, E., The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development. Hanover, N.H.; London: University Press of New England, pp. 49–68.

Stimpson, C. R. (1983) ‘Doris Lessing and the Parables of Growth’, in Abel, E., Hirsch, M., and Langland, E., The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development. Hanover, N.H.; London: University Press of New England, pp. 186–205.

The Intersection of the Demonic and Ecological Spaces in German Modernism

Amy Ainsworth (University of Cambridge): I am a 1st year PhD student researching the demonic as it may be traced in different kinds of primarily ecological space in German modernist literature, and the implications of its presence for those who must navigate these spaces. I am exploring the links between the use of the demonic as a literary device and the encroachment of modernity, the impact of the demonic in ecological spaces on the individual psyche, and the ways in which these ideas might inform our approach to the environment in modernist literature.

The demonic appears persistently throughout Western literary history, manifesting itself in a number of ways: as a destructive negative drive, as the persistence of irrationality in a supposedly rational world, as an enormously powerful creative energy. Given the intrinsically ambivalent nature of the demonic, it may materialise as a combination of these, and in other ways entirely. My research draws on a significant body of theoretical work on the demonic, whilst exploring the concept in a context rarely touched upon. The demonic is frequently linked with character – with the experience of the individual – but it has rarely been explored in a spatial context. My work examines the intersection of the demonic as a mysterious, irrational and profoundly powerful force or energy with different kinds of ecological space in German modernist texts.

The demonic as it emerges in a literary context as an unknowably, highly generative but potentially destructive force appears particularly potent when it can be found in natural spaces. Goethe, for example, who produced significant theoretical work on the demonic, linked the concept with the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, which appears to have had an enormous impact on the young writer. His work demonstrates profound awe and a respectful fear of the demonic as an unknowable, chaotic and uncontrollable force which moves through nature. There is therefore a precedent here for spatialising the demonic in an ecological context. Working in a German context, my research necessarily draws on Goethe’s theoretical work, which contributed in a significant way to the German conception of the demonic. It differs from the English-language understanding of the concept, in which it is more frequently linked with Judeo-Christian notions of evil. In a German-language context, although these links are still present, the demonic is often read – due in part to Goethe’s writings – as a powerful energy which may be simultaneously highly creative and profoundly destructive.

My own exploration of the literary demonic in ecological spaces focuses on modernist literature. These spaces as they are represented in modernist texts have previously been neglected as a focus of research, given modernism’s engagement with the individual’s psyche rather than with the external world. I would argue, however, that natural spaces in modernism have much to offer: they are frequently disquieting spaces which reflect or challenge the psychological experience of those who must navigate them. They are also not merely subordinate to human agendas – they are not simply there to be exploited. Rather, they foreground the ‘more-than-human’, which frequently takes the form of the demonic as a powerfully productive and destructive force. Locating the demonic in these spaces may therefore offer a new way of reading these spaces ecocritically. Those who come into contact with these modernist spaces are almost always forced to contend with a ‘something’ lurking behind them – an unknowable and sometimes threatening force which I will argue emerges particularly intensely in natural spaces. These are spaces which resist human exploitation, and in this literary context they have significant creative and destructive power. My current work explores these ideas as they appear in literary swamps and wetlands, with a focus on Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella Der Tod in Venedig (Death in Venice) and Stefan Zweig’s perhaps less-known but highly significant 1922 work Der Amokläufer (usually translated as Amok). These texts feature two very different kinds of swampy space: Venice, the swamp city, and in Der Amokläufer, a colonial outpost in which the unnamed protagonist attempts to escape his life in Europe. Both characters – middle-class, professional men – seek escape in the swamp but are forced to contend with more than they bargained for. The swamp, historically reviled and even feared, is a space of contradictions: it is lively and dangerous, teeming with life yet associated with death and decay. The demonic, as a force which is itself simultaneously representative of enormous generative potential and of destruction (frequently of the self), thrives in this kind of space. In both of these literary works, the swamp consumes the individual who attempts to navigate it in order to find escape in the unfamiliar exotic. These spaces are mysterious, powerful in their own right, and not quite controllable. They have a huge and ultimately fatal impact on the physical and psychological experiences of the protagonists of these texts. Tracing the presence of the demonic in these works demonstrates the immense potential of ecological spaces in literature, and is a fascinating way of exploring the representation of the psyche in modernist texts.

Amy Ainsworth, PhD student, University of Cambridge

German Jewish Perspectives on Home and Belonging – Sasha Salzmann and Max Czollek

On 4-5 June 2020, my colleague Godela Weiss-Sussex (IMLR) and I had planned to hold a two-day international conference at the Institute of Modern Languages Research with the title “From ‘Where are you from?’ to ‘Where shall we go together?’ Re-imagining Home and Belonging in 21st-Century Women’s Writing”. When the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, we decided to postpone the event which will now take place in the autumn of 2020. To still mark the dates of the initially planned conference, this blog entry engages with some of the key questions motivating our event from the perspective of contemporary German Jewish literature and culture by showcasing a short reading by Sasha Salzmann and an interview with Max Czollek. We look forward to presenting and discussing the many other approaches that will be part of our conference programme later this year, and we hope that this blog post will be the start of a fruitful exchange around the topics of home and belonging in 21st century literatures and cultures.

“Heimat” and Contemporary Germany

In the so-called “century of the migrant” (Nail 2015, 1), the meanings of “home” and “belonging” are shifting on a global scale. They are becoming more plural, fluid and entangled across national, cultural and linguistic borders, and the notion of home as a fixed location is being augmented by emphasising the process of “home-making” (Meskimmon 2011, 29) across spatial and temporal borders. At the same time, we are witnessing the return of violent nationalisms across the globe, oftentimes fuelled by a desire to turn back the clocks and reinstate (an always imaginary) homogeneity as the norm. These ambivalences are also visible in the contemporary German-language context, not least because Germany has such a complicated relationship with concepts of home and belonging. The German notion of “Heimat” (home/homeland/sense of home), which is hard to translate into any other language, has a deeply problematic history that connects the term to various manifestations of German nationalism, which found their most violent outpouring in the period of National Socialism. In recent times, debates around what “Heimat” might mean in the German context, and how to deal with the concept and its legacy, have resurfaced, not least in response to the arrival of several thousand refugees and asylum seekers from the Middle East and Africa since 2015. These discussions resulted in, on the one hand, conservative re-appropriations of the term, as evidenced by the 2018 renaming of the former Bundesministerium des Innern (Ministry of the Interior) into Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat or “Heimatministerium” (“Heimat”-Ministry). One the other hand, there are attempts to engage differently with notions of “Heimat” and belonging from the perspective of younger generations, as is the case for Nora Krug’s hugely successful graphic memoir Heimat (2018) or Saša Stanišić’s critically acclaimed account entitled Herkunft (Origins, 2019). And then there are those who reject “Heimat” completely, arguing that it cannot be untangled from exclusive and homogenising notions of belonging. A recent collection of essays entitled Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum (Your Home is our Nightmare, 2019) aims to give voice to all of those who have never been included in the concept of “Heimat” in the first place, while the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon at the Maxim Gorki Theatre challenged present-day German society to “Deheimatize it!”. It is perhaps unsurprising that these attempts come from individuals who are, in Fatima El-Tayeb’s words, constructed and considered as “undeutsch” (un-German) – “als nicht nur nicht zur nationalen Gemeinschaft gehörend, sondern diese durch ihre Anwesenheit gefährdend, destablisieriend” (not only do they not belong to the national community, they are also imagined to endanger and destabilise it by virtue of their sheer presence) (El-Tayeb 2016, 34). As such, individuals from “undeutsch”, minority backgrounds are continuously confronted with the dark and nightmarish side of “Heimat”, which affects all those who are not included in this supposedly idyllic space. As El-Tayeb and others argue, the concept’s seemingly harmonising potential actually depends on the exclusion of individuals and groups who are imagined as “Other” – hence the idea that one person’s home is another person’s nightmare.

The three approaches to “Heimat” outlined here – conservative re-appropriation, critical re-examination, and wholesale rejection – are part of a wider reassessment of belonging and “Heimat” in present-day, “postmigrant” Germany. As Naika Foroutan has argued, the underlying conflict in “postmigrant” societies, i.e. societies that renegotiate their epistemological, normative and institutional frameworks in the wake of large-scale migration movements, concerns the issue of plurality (Foroutan 2019). A strengthening of conservative notions of “Heimat”, which correspond with homogenizing and, in some cases, “(neo-)völkisch” thinking, can be seen as one strategy of rejecting the actually existing and increasing plurality in a “postmigrant” Germany. On the other side of the spectrum, the editors of and contributors to Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum and the organisers of the Herbstsalon seek to counter these strategies by acknowledging and promoting pluralistic, “deheimatized” notions of belonging.

A key area in which such re-assessments are currently taking place are the arts, which, as some argue, are more suited to develop new and alternative visions of belonging and togetherness: “Political discourses are not the only forums, and rarely are they the first in which the effects and affects of migration and plurality are felt and negotiated. In fact, stories of postmigration […] are created in everyday life and especially in the arts” (Ring Petersen et al. 2019, p. 58). It is for this reason that we have asked two prominent and leading voices in contemporary German Jewish discourse to give us their take on questions of home and belonging. While both are writers, they are also actively involved in the German-language cultural sector as curators of various artistic and creative platforms.

Unhomely Homes – Sasha Salzmann

In the video clip below, German Jewish author and playwright Sasha Salzmann, who also collaborates closely with the Maxim Gorki Theatre’s Studio Я, is reading from the English translation of their highly acclaimed debut novel Ausser Sich (Beyond Myself, 2017). The question of belonging – and of how we can think belonging differently – is, arguably, at the centre of the entire text. The novel’s title implies a subject that is somehow beside itself, that does not fully belong to itself. Belonging, or rather a definite knowledge of where one belongs, which is something that is often taken for granted in political discourse, is thus presented as improbable, maybe even impossible. A stable, rooted sense of identity is contrasted with what one could call, in the words of Édouard Glissant, “relation identity” (Glissant 1997, 144) – something that is not a given or an essence but that only exists in relation to otherness. Salzmann addresses some of these concerns in her reading of a chapter from the book entitled “zu Hause”/“Home”:

In the book, the quotation marks surrounding the chapter’s title signal a distance from the concept of home, pointing to complications of belonging: upon returning to his homeland Russia after migrating to Germany with his family, the protagonist of the chapter, Anton, has to realise that the place he considers home is no longer homely. What is more, he has to learn that this home was never his in the first place – as a Jew he was never a part of the imagined community of his homeland. This disenchantment with “home” also affects Anton’s father, who had hoped to find a (better) home in Germany. Although Salzmann’s reading leaves open what kind of account he will give of the family’s new home “Germania”, the fact that he had to rehearse his ostentatiously jovial answer beforehand signals that this new home also is not what it initially seemed. The chapter thus stages a clash between expectations and realities, between an individual’s choice over their sense of belonging and belonging as something that is imposed from the outside. Belonging is thus precarious and ambivalent and so is the notion of being “zu Hause” (at home).

De-integrating, De-heimatizing – Max Czollek

The ambivalences of home and belonging are also central for Max Czollek, who works as an essayist, poet, journal editor and curator. He rose to prominence with the publication of his recent polemic Desintegriert euch! (De-integrate Yourselves!, 2018). The book makes the case for a Jewish emancipation from what could be described as an imposed sense of belonging, namely the roles that Jews in Germany have to perform in what Czollek denounces as the German Jewish “Gedächtnistheater” (theatre of memory). Pointing beyond German Jewish discourse, Czollek stresses that many other minorities are also trapped in roles that hamper the expression of more multi-facetted, pluralistic senses of identity. What is thus needed are notions of belonging that can account for and accommodate the already existing diversity of contemporary German society. In the following interview, we asked Czollek about his take on home, belonging and integration and about how we may be able to imagine these differently in the future.

- Since our conference is concerned with renegotiations of home and belonging, we’d like to start by asking you what your understanding of home is, maybe with a particular view to the complicated German notion of “Heimat”.

Max Czollek: I’d like to start by differentiating between a political notion of “Heimat” and a personal idea of belonging and home. My critique is directed towards the political concept. I argue that the political notion of “Heimat” is one of many concepts producing the difference between those who are already here (“Germans”) and those who are coming from “elsewhere” (the Other, i.e. Migrants, Muslims, Jews, …). It is thus strongly connected to the demand for the Other to adapt to a specific notion of Germanness whose outlines remain blurry. The curious twist on “Heimat” is that people will always assure you that they harbour only the best intentions like using “Heimat” to make people feel at home and to identify with their respective community. The thing is, however, that you don’t have to want people to be excluded in order for them to be excluded. And if you say “Heimat” you are drawing on a specific German tradition of one people, one territory, one nation that will produce its own modes of discrimination. And we can see this happen today.

- Your work is very critical of certain dominant conceptions of belonging, as they for example manifest themselves in the integration paradigm. What is your problem with the notion of integration and how could we, in your view, re-think belonging along different lines?

MC: The concept of integration is another concept producing the difference between those who are here and those who are coming. Usually formulated as a demand (Integrate yourselves already!) or a lack (they are not integrated enough), it introduces three central aspects to the debate around belonging: (1) a specific albeit invisible group ascribes to itself the power to define who belongs and who doesn’t, (2) by calling on in-tegration society is being imagined as a place with one centre, and (3) the fantasy of integration rests on the idea that society needs homogeneity and harmony to function. I’d argue that you can find the first two points in other countries, the latter concept is connected strongly to a German idea of society and what it needs to function. Homogeneity and harmony, however, are not the basis of modern pluralistic democracies. Democracy, on the contrary, means a process of constant negotiation and struggle and this will continue to be so unless society succumbs to the homogenising demands of totalitarianism and authoritarianism.

- Can you say something about the German Jewish situation vis-à-vis the questions of belonging and integration raised above?

MC: The Jewish minority holds a special position in German society and its self-construction after 1945. In its endeavours to reconstruct the notion of a positive German national identity, “the Jews” are called on to perform a specific “ideological work” within the “Theater of Memory”. Both terms where introduced by Sociologist Michal Bodemann. The “Theater of Memory” is based on the interaction between the redeemed and rueful perpetrator society and its descendants on the one side and the surviving Jews on the other. This leads to a peculiar situation specific to the Jewish minority: because of its intense symbolic significance Jews and their perspectives are very visible – but this visibility is restricted to the roles assigned to them in the German “Theater of Memory”. There is no place in this for Jewish diversity extending beyond the boundaries of a perpetrator-victim binary.

- You are not only a political commentator but also a poet and performer – can you briefly comment on the interrelation between art and politics in your work? In what way do you think artistic discourse can or cannot contribute to broader socio-political developments?

MC: Instead of making a normative statement on the significance of art for each and every one of us, let me point to the empirical significance art and culture has assumed in the last decades in discussions about the future of the German society. This has been especially true for those minority groups that found themselves outside the established institutions of conflict resolution such as the trade unions and party politics. From the art-collective Kanak Attak to the post-migrant theatre of Shermin Langhoff, from stage-occupations by Jewish activists to the development of Hip Hop – art has served as a laboratory for discourses and perspectives that only later moved to the political sphere. For me, the question, therefore, is not if art can or cannot contribute to broader socio-political developments but in what way it does so and how we can accord more weight and attention to artistic interventions into the contemporary situation.

- Our conference brings together participants and scholarly work from a range of places, which are not limited to the German-language context. Can you say something about if and how the German-language (Jewish) background that you outline in your work relates to broader transnational debates and other linguistic contexts? Do you see potential for transnational solidarities and cosmopolitan affiliations?

MC: My work is deeply indebted to the works of James Baldwin, Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, bell hooks and many others. At the same time, it is closely connected to the specific German constellation of a Jewish experience, (post-)migrant communities and a hegemonic culture and its desire for normalcy and redemption. And I can hardly imagine any other way to deal with the challenges and complexities posed by the contemporary situation than to be as specific as possible. At the same time, I find similar notions in places ranging from the US to Israel, China to Argentina. There seems to exist a global and globalized critique of discrimination we share with each other and a localized adaptation whose premises are always in need of an explanation. This is not merely a question of precision but also of the recognition of the equal value and specificity of our perspectives on discrimination. Transnational solidarities rest on two things – the agreement on a certain set of values. And the ability to listen to and respect each other’s perspectives.

In the context of our upcoming conference on renegotiations of home and belonging in 21st century women’s writing, we hope to develop further some of the questions raised by Salzmann’s and Czollek’s contributions. It will be particularly interesting to see how the issues highlighted here connect to and differ from other national, cultural and linguistic contexts and what contribution (women’s) writing can make to these present-day political concerns.

Maria Roca Lizarazu, University of Birmingham

Mental Health Discourse: Taboo or Stigma?

Ffion Brown (Manchester Metropolitan University): I am a 2nd year PhD student researching how public perceptions of gender and mental health influence the way men linguistically construct their experiences with mental illness.

While there has been an increase in awareness on mental health in recent years, discourse related to mental health, especially mental illness, continues to draw upon taboo or stereotypical language in media representations (e.g. Simmie & Nines, 2002; Corrigan, 2004; Atanasova et al., 2019). This suggests that mental health discourse remains to be taboo within society and it is worth considering why that is and how reproductions of discourse continue to contribute to that taboo.

An aspect to mental health literature that will be discussed here is the relationship between the terms ‘taboo’ and ‘stigma’, both of which are prevalent in linguistic and medical examples of literature when discussing the more social contexts of mental health research. However, there is a tendency in the literature to use these terms almost interchangeably, highlighting that their use in this context is ambiguous and demonstrating a need to distinguish between them. Therefore, how are we able to understand this distinction in mental health discourse if their usage seems to be similar?

Firstly, taboo is defined in the dictionary as ‘a practice that is prohibited or restricted by social or religious custom’ (Taboo, n.d.), although it is suggested that taboo can also be abstract and refer to many ideas at any one time (Jay, 2009). This could lead to more taboos being imposed by society, allowing the concept of taboo to be extended to mental health discourse due to how it has been reproduced by the public. Secondly, stigma as a concept follows a similar negative pattern as taboo, although it tends to be used more as a feeling towards a person who is ‘discredited’ from other society members (Goffman, 1986: p.20). Further to this, the dictionary definition goes so far as stating that stigma is ‘a mark of shame’, (Stigma, n.d.) indicating something or somebody as being shameful. It is this fear of being signalled as different, or stigmatised, that impacts how someone would engage with relevant services and possibly result in uncertainty amongst members of the public due to a lack of information (Corrigan, 2004).

Given that the two concepts are related to one another, how then does stigma become taboo and vice versa? Hudson and Okhuysen (2014) posit that it is through social stigma that society can identify what is taboo, learned ‘through the socialization of speech practices’ (Jay, 2009) and the implementation of social sanction. One way in which social sanctions allow for the continued existence of mental health being taboo is the perceived reactions from others in society. This is where feelings of stigma come into play with the concept of taboo, hinting at the idea that through indulging in taboo practice or taboo discussions can lead to being signalled as different or ‘undesired’ (Goffman, 1986, p.11) to one’s peers. As a consequence, feelings of stigma could result in less service participation and less public discussions of mental illness, allowing for more negative stereotypes and imagery to come to fruition with no dispute.

While they do seem to be used interchangeably in the literature, if we take everything into consideration, ‘taboo’ and ‘stigma’ are two different concepts that work in conjunction with one another where taboo relates to a restricted practice or discourse and stigma is how that taboo is felt amongst society members. Yet, how can we identify this distinction in public representations of mental health discourse?

One crucial element of identifying why mental health is taboo in discourse is by exploring what types of representation take precedence within media reproductions. Corrigan, Markowitz & Watson (2004) indicate that ‘when the news media portray a group in a negative light, they propagate prejudice and discrimination’ (p.483). Referring back to a fear of being signalled as different (Corrigan, 2004) this can be applied to multiple types of discourse, including mental health as a way of introducing stigma. By negatively framing certain topics, society members become afraid of being viewed in the same way and therefore restrict themselves and others from being associated with that topic and thus contributing to the taboo concept.

Stuart (2005) states that ‘negative news stories grew at a faster pace’ (p.25) in comparison to positive stories when dealing with mental health as a topic. This means that as a taboo concept, mental health discourse will continue to be referred to as such and it would be difficult to overcome that when negative imagery is consumed more often than the positive. This is especially the case when stereotypical language of violence and incompetence is argued to be a cause for feelings of stigma amongst those who suffer from mental illness (Abdullah & Brown, 2011).

Ffion Brown, PhD student, Manchester Metropolitan University

References:

Abdullah, T., & Brown, T.L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 934-948. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003

Atanasova, D., Koteyko, N., Brown, B., & Crawford, P. (2019). Representations of mental health and arts participation in the national and local British press, 2007-2015. Health, 23(1), 3-20. DOI: 10.1177/136345931

Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614-625. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

Corrigan, P.W., Markowitz, F.E., & Watson, A.C. (2004). Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30(3), 481-491.

Goffman, E., & Goffman, E. (1986). Stigma : Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Hudson, B.A., & Okhuysen, G.A. (2014). Taboo topics: Structural barriers to the study of organizational stigma. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(3), 242-253. DOI: 10.1177/1056492613517510

Jay, T. (2009). The utility and ubiquity of taboo words. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 153-161. DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01115.x

Stigma. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stigma

Simmie, S. & Nunes, J. (2002). The last taboo : A survival guide to mental health care in Canada. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

Stuart, H. (2005). Fighting stigma and discrimination is fighting for mental health. Canadian Public Policy, 31(22), 22-28.

Taboo. (n.d.). In Lexico powered by Oxford’s online dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/definition/taboo