Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

A book about the little joys of life: ‘Vovô Tsongonhana’ by Augusto Carlos

Vincenzo Cammarata, PhD student at King’s College London, reviews Augusto Carlos’ Vovô Tsongonhana

Looking at the simple things in life, Vovô Tsongonhana (2005) describes the lives of an old man and a child, searching for happiness and harmony with the surrounding world. The message of this book is clear: people should be grateful for what they have and help each other. Sharing is caring, as we all know. Speaking with the voice of an imaginary story-teller, Mozambican writer Augusto Carlos narrates the story of an old street seller from Congolote, who regularly goes to Maputo to sell his artefacts, and one day decides to take a child off the street. The plot is linear: an old man, Moisés, nicknamed Tsongonhana (meaning little, short), brings an orphan child home and teaches him manual jobs, such as carving statues made of mafurreira roots, so he can sell them and make a living from it. This nameless child, called by the others Bula-Bula for talking too much, is then named ‘Duda’ after Tsongonhana’s deceased brother.

A touching story filled with optimism. Despite all the difficulties encountered, Moisés doesn’t stop hoping. He lost his wife and his two sons vanished, so Duda becomes his new family and the promise of a brighter and prosperous future society, based on equality and justice. Tsongonhana gives daily lessons of life, discussing his views about today’s problems. In his opinion, people should look back in history and think of a way out of the misery brought by years of wars and corruption. Wars are always wrong, they separate families, displace people, many of them die, destroy everything and cause starvation. In a world where people raise up barriers and build up walls, Tsongonhana’s vision of a global community, where each member mutually supports each other for the greater good, is like a ray of light in this dark age of separations. The old man also acknowledges the concept behind the European Union, a broad form of international cooperation formed by several countries, including those that historically took part in the infamous Scramble for Africa. In his mind, Moisés wishes that every country of the world was included in such form of cooperation, supporting each other, in everyone’s interest.

The sun shines on everyone. To achieve happiness and freedom, Moisés thinks that men should try to find themselves by re-establishing a lost contact with the surrounding nature. Talking to plants, stroking them, staring at the beauty of the world are all part of a process of reconciliation to where we belong. Each human activity should be carried out in accordance with the rhythm of nature. Animals deserve respect and it’s necessary to give them some time to complete their biological cycle, it’s not all about satisfying human needs, even if you are a hunter. The mafurreira, mentioned several times in the book, is a symbol of self-sustainability, as this gives the raw material to make statues and sell them in the market, but is also an indissoluble bond between men and their land. These plants have feelings like humans, as the author makes them ‘wait’ to have their roots picked by Tsongonhana and Duda in the early morning, when the sun is rising. Mafurreira trees also ‘cry’ when the old man dies, but the author/story-teller doesn’t know if those are tears of nostalgic sadness or happiness for a future re-encounter. When the spirit of Moisés leaves his body like a mamba (snake) changes its skin, the narrator tells us that the mafurreira tree would soon host Moisés’s spirit, as it becomes the place where everyone commemorates Moisés on his final farewell.

‘Conversas à volta da fogueira’. For its colloquial language filled with local words coming from the Bantu languages spoken in Mozambique, Vovô Tsongonhana is meant to be read aloud. As a narration within a narration, the writer tells the whole story as if he is talking to his readers, who are sat around a fire, holding a conversation (conversas à volta da fogueira). Within this narrative frame, Moisés evokes his memories and tells stories of his life to Duda, as well as the other children of the streets of Maputo. The importance of talking face to face, sharing experiences, ideas, is part of a long educational process, moulding the characters and sharpening the minds of the future adults. Thanks to his oratory skills acquired through experience, Tsongonhana advocates the importance of the elderly in society and their educational role as an invaluable source of knowledge. Oral literature collects the stories of the predecessors with the help of memory, that writes, like an invisible ink, the pages of History. Without a clear-cut distinction between story and history in oral tradition, where the real and the fictional may mutually interfere, Moisés says that everybody’s history is the consequence of their parents’ lives, that, in turn, were the continuation of their parents’ lives, and so on, up to the very beginning of everything. Every story is important; even the smallest one, contributes to the development of history. People need to learn History to understand the present and build a better future.

A book about the little joys of life. What makes us happy? How do we achieve happiness? Living in a world where simple things tend to be overlooked or even ignored, this book is worth being read to gain a more positive outlook towards life. We need to know where we come from to understand who we are and where we are going to. Experience and mutual help build a healthy society, and Moisés knows it. The wise words of Tsongonhana are food for thought. Overall, I must say it is a short but very enjoyable reading; thanks to the words of the elderly man, Duda walks through an imaginary path towards a prosperous and harmonious world, surrounded by mafumeira trees, where everyone lives in peace with each other.

Vincenzo Cammarata, PhD student, SPLAS (Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies) King’s College London

Encountering COVID-19: Lessons from Languages

As increasing numbers of epidemiologists and journalists highlight how the UK government consistently missed opportunities to tackle the spread of the new Coronavirus and the respiratory disease it causes (COVID-19), questions about the role of language and narrativisation have yet to be asked. Dr Joseph Ford discusses some of them.

Pressure on governments to tackle the fallout from the spread of COVID-19 across the world has been intense, but scrutiny of the initial actions taken by UK and US governments has been particularly probing in recent days. However, while public health experts like Helen Ward have criticised politicians who ‘refused to listen’ to scientific advice, they stop short of asking why politicians like Boris Johnson and Donald Trump ignored the advice of the World Health Organisation (WHO) and failed to follow the lead of countries such as China, Taiwan or South Korea (all of whom have managed to successfully suppress the virus with extensive testing and contact tracing measures).

To ask why countries like the UK and the US took so much longer to learn from the worrying signs coming out of China, or to listen more quickly to the advice of the WHO of course means asking difficult questions about the actions of the Chinese government and of international bodies such as the WHO. China is widely reported to have suppressed news of the detection of the virus, while the WHO ignored early warning signs from Taiwan back in December, because the UN does not recognise the country as a sovereign state.[1] But to watch politicians such as Trump incite racism and xenophobia, labelling the new Coronavirus a ‘Chinese virus’, or Johnson smirk at the idea that many in the UK were not following social distancing advice – and this, after having spent weeks ignoring warnings from the WHO and other countries experiencing the virus – demonstrates a sense of Western exceptionalism and scientific superiority that, as we are now learning, would never keep the virus at bay.

In France, meanwhile, racist narratives of colonial science have been shown to be alive and well, as two French scientists openly discussed the possibility of testing a Coronavirus vaccine in Africa, in order to verify its effectiveness on a population apparently already more vulnerable to the virus. The 1920s saw large-scale vaccination campaigns against sleeping sickness in Cameroon, the Central African Republic and the French Congo, when a handful of needles where used to immunise thousands of people. And, while these two scientists mention the testing of vaccines to control the HIV-AIDS epidemic, they are ignorant of claims that it was precisely the actions of Western virologists in Africa that led to the release of the HIV virus on the continent.[2]

There is a certain irony to both Johnson’s familiar smirk and the French scientists’ suggestion. In her article for the Guardian, Ward notes that it was precisely during those two wasted weeks before Johnson introduced a full UK lockdown that the prime minister was most likely to have contracted the virus, which led to his own hospitalisation and admission to intensive care. Meanwhile, African nations have shown superior levels of preparedness for the ongoing outbreak, and many nations have been aware of the importance of early testing and contact tracing. Three weeks into the lockdown in Rwanda, 110 confirmed cases of COVID-19 had been confirmed, while no deaths have been recorded yet. Compare that to more than 100,000 confirmed cases and 10,000 deaths in France, which after accounting for different population sizes is nearly two-hundred-times the Rwandan figures at the equivalent stage of the lockdown. Of course, this could all change, but African nations have not made the same mistakes that Europe and the US made in the early days of the crisis.

Amid these ironies and the actual science, there are fundamental questions to be asked about the capacity of Europe and the US to think critically about their initial responses to the spread of the virus in the rest of the world, and crucially about the way the West has narrativised the Coronavirus as ‘coming from’ the East. The virus has been clearly linked to regions of the world that the Global North considers ‘dirty’ or ‘unhygienic’, revealing racist tropes that are embedded in our language. The naming of previous respiratory viruses such as MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) by geographical location undoubtedly contributes to this problem.

In departments of languages and cultures across the UK, we have been at constant pains to stress that a languages education goes way beyond the skill of learning a language. To quote Julian Barnes, to understand another language ‘is to understand those who speak it.’[3] But language learning is not simply about common understanding of existing languages or cultures, it is also, as Alison Phipps writes in her book on the decolonial practice of language learning, about ‘changing human relationships of power around speech and language’ (2019: 26). This means acknowledging that at the heart of our encounters with other languages and cultures is a relation of power – and frequently an imbalance of power that privileges one speaker over the other.

These are precisely questions we have begun asking here at the Institute of Modern Languages Research (IMLR). Together with colleagues across the UK and the US, I and Emanuelle Santos from the University of Birmingham had organised a two-day symposium in March, which promised wide-ranging discussions about how imperial and colonial forms of knowledge-making impact on the teaching of languages. Yet, at the core of this project is also a question about how language learning is uniquely placed to encourage critical and self-reflexive understandings of the histories of power that configure and construct the ‘knowledge’ upon which our contemporary politics, society and science are founded.

Contained within the pages of Phipps’ recent book is the insight of the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe, who, some twenty years ago, wrote how ‘the experience of the Other […] has almost always posed virtually insurmountable difficulties to the Western philosophical and political tradition’ (cited in Phipps 2019: 43). It is often remarked that politicians like Boris Johnson possess superior cultural knowledge of the world, of ‘the Other’, through speaking languages (he apparently speaks French and Italian fluently and knows Latin). However, we must learn to understand that we cannot simply ‘know’ the world through learning dominant Western European languages, but must instead learn the redeeming powers of everyday encounters with languages and cultures we do not, and perhaps cannot fully ‘know’.

Indeed, we are learning about the virus and its impact on our bodies and our thinking every day. But it is vital to acknowledge that the virus was, and to a large extent still is, a scientific unknown. Scientists have very quickly gathered and accrued data and subsequently published knowledge about the virus and its effects, but this process of creating knowledge comes after an initial encounter with the unknown. The lesson from languages is that we are ‘encountering’ this virus as an unknown ‘Other’ and it is precisely this ‘encounter’ for which we were (and remain) unprepared. While there is little doubt that the demands of maintaining the liberal economic order have played a role the UK and US governments’ reluctance to enforce and maintain lockdowns, presumptions around superior science, or the specifically Western pre-eminence in acquiring data and synthesising ‘knowledge’, reveal the imperialist thinking at the heart of the Western political unconscious.

The Coronavirus has caught scientists off guard, as they rush to write new science, but decolonial perspectives grasped through linguistic and intercultural encounters, allow us to see the dangers of assuming our ‘knowledge’ or ‘science’ is superior to that of the Global East or South. Data does not exist in a vacuum, but circulates in a cultural ecosystem carried by languages. As the UK and the US look likely to be two of the worst-affected countries in this Coronavirus pandemic, it is vital that we examine how narratives of Western and European exceptionalism in the minds of politicians and scientists have led to the dither and delay that has already claimed so many lives, and will needlessly claim many more.

Dr Joseph Ford, ECR French Studies, IMLR

For a preview of the forthcoming symposium, ‘Decolonising Modern Languages: A symposium for Sharing Ideas and Practices’ (final dates TBC), see here.

[1] The reason Taiwan responded so quickly to the spread of the virus was because of their shared language with China and the fact that several Taiwanese citizens in Wuhan raised the alarm. Thanks to Thom Abbott for pointing this out to me.

[2] Thanks to Sarah Arens for highlighting these claims.

[3] This is taken from Charles Forsdick’s Twitter feed.

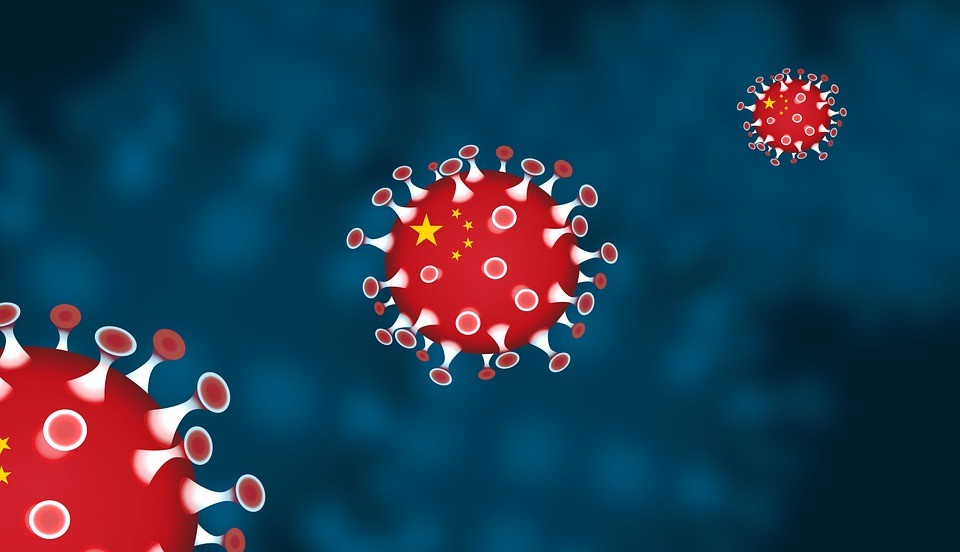

The Clothes on our Backs

Dr Anna Nyburg introduces her latest book and reveals how Jewish refugees brought design to the British clothing industry.

Anyone looking for an entertaining read in these difficult times could do worse than The Clothes on our Backs; How Refugees from Nazism Revitalised the British Fashion Trade.

Fans of 20th-century textiles will be well acquainted with the work of Jacqueline Groag, Marian Mahler, Tibor Reich and others. But they may not have made a connection with brands such as Kangol, Ettinger or Charnos. And yet both the textile designers and the manufacturers of berets, wallets and underwear share a common story: they were all refugees from Nazi Europe. Some 80,000 people came to safety in Britain before the outbreak of World War II. Most of these refugees were Jewish, or classified by the Nazis as such. Jews have long been active in the textile and clothing trades, since the Middle Ages in fact, when one of the limited options open to them was to walk across the country selling second-hand clothes and lengths of fabric. This was the beginning of the ‘rag trade’.

By the time of their emancipation in the 19th century, they had clocked up not only miles but also experience and skills: they knew who bought what, where and at what price. In the first two decades of the 20th century, they moved quickly from creating small fabric and tailoring shops, to founding modern department stores in Berlin and other cities in central Europe. These sleek modernist buildings were not just where women could now buy ready-to-wear clothes fit for their increasingly liberated lifestyle, but also hosted fashion shows and other fashion events.

Berlin in particular was the centre of prêt-à-porter: the manufacture, marketing and display of fashion garments took place in the capital of Weimar Germany. Along with Vienna, Budapest and Prague, it was a city where students could study textile design but also window display, fashion illustration and photography, subjects that were not usually on offer in British colleges as that time.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler came to power and with it came a threat to the livelihoods and, indeed, lives of the textile and clothing producers. Britain was one of the few countries where they would be safe from the Nazi menace. Just two who made it to asylum in Britain were Jakob Spreiregen and his nephew Joseph Meisner, Poles who had previously emigrated to France where they had set up their first hat business. They made berets by the traditional method of knitting an open shape, the top of which was joined up by hand, a process known as linking. Spreiregen arrived in Cumbria in 1937, taking advantage of a clever and creative scheme by local government to, on the one hand, save the lives of threatened Jewish industrialists in Europe and, on the other, bring much needed employment to the North of England. Kangol (K for knitting, ANG for Angora and OL for Wool) started in Cumbria with only four workers who had to learn beret making without the benefit of a shared language with their francophone employees. When war broke out it was Kangol who were given the order to make fatigue headgear for the armed forces. Who can think of Field Marshall Montgomery without his Kangol beret? Refugees, now ‘enemy aliens’, were largely interned on the Isle of Man unless they joined the Pioneer Corps or were engaged in production for the war effort, like Kangol. After the war, the company went from strength to strength, making the berets for the British Olympic team in 1948, followed by a Beatles model in the 1960s and a furry ‘furgora’. Kangol, like many other refugee entrepreneurs, were able exporters and, unlike their British counterparts, were not daunted at the thought of learning another foreign language or travelling, two experiences they had already weathered. Kangol won several of the Queen’s Awards to Industry for Export Achievement. Still trading today, albeit no longer from Cumbria, Kangol have celebrated their 80th birthday.

Among the many other refugees who made their mark in Britain were the founders of Silhouette, two German families who made underwear. The Silhouette story includes a radioactive corset, the fabulously successful ‘Little X’ girdle and a Silhouette musical.

Some came as designers, like the talented and tenacious Otto Weisz from Austria who landed the job at Pringle of Scotland’s first professional knitwear designer. It was he who came up with the concept of the twinset, that most British of outfits.

Then there were the refugee fashion illustrators, window display designers, photographers, journalists: they had every aspect of fashion covered, and British fashion flourished. Many of the companies are still trading today, although few people know the story of their desperate flight to Britain where they found a home but gave us in return employment, new design and technology, new fabrics and display practices.

Anna Nyburg is Lecturer at Imperial College London, and a Member of the Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies at the IMLR

The Clothes on our Backs. How Refugees from Nazism Revitalised the British Fashion Trade by Anna Nyburg was published in February 2020 by Vallentine Mitchell. Paperback copies can be bought directly from the author a.nyburg@ic.ac.uk at £15 (includes UK postage) or hardbacks are available from the publisher at £55.

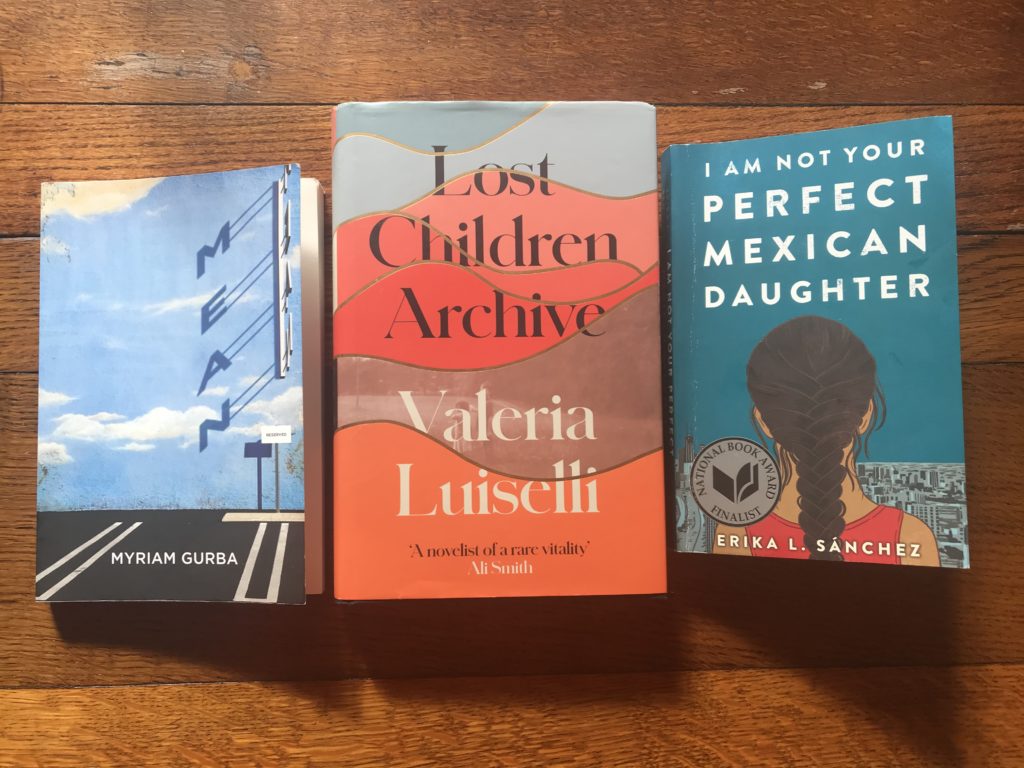

‘What are you reading?’ What (Not) To Read: Mexico-US Border Trouble, from Niamh Thornton

In early January and February 2020 an on- and off-line publishing storm unfolded over the publication and promotion of American Dirt (2020). Prompted by a lively and scabrous post describing it as “a racist brownface novel”, much of the debate ranged around the fact that it was receiving undeserved attention from influential celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey through her Book Club. Those who joined the fray were fellow Latinx authors angry at yet another narrative revisiting tired clichés about Mexicans and migration. There is much to learn through tracing the discussions and activism that coalesced in response to this novel when we think about who gets to tell stories and how the publishing industry and book promotion operates in the US (and elsewhere). I’ve mapped out some of this discussion previously, and I am sure there will be further scholarly work done in the near future. Meanwhile, prompted by the fact that the book has received a degree of “cultural consecration” (Bourdieu 2010 xxiv) in the UK featuring as it has on the BBC as Book of the Week (6-16 of April 2020), and inspired by others who have taken the opportunity to draw attention to authors that do merit attention, I would like to suggest alternative reading if you want to understand Mexican-US relations and its consequences on individual lives.

A post by Myriam Gurba prompted the discussion about American Dirt and, as a result, it is worth finding out more about her via her memoir Mean (2017). Whilst it is structured around a life-altering violent incident, much of the book considers what it means to come of age and come out in a small city in California as a Polish-Mexican. Often darkly humorous and sometimes self-effacing Gurba explores why being mean becomes a survival strategy in the face of racism.

Also centred on a violent incident, the young adult novel by Erika L. Sánchez, I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter (2019) explores the precarity of being the daughter of undocumented Mexican migrants in the US. The accidental death of Olga leads her sister, Julia, to find out more about someone she soon discovers was not the perfect daughter her parents had presumed she was. Told in a similarly darkly comic and energetic style to Mean, Julia’s quest is as much about figuring out her own future as it is about coming to terms with who her sister really was.

Another book that looks at childhood and the US border is the multi-award winning Lost Children Archive (2020) by Valeria Luiselli. It follows on from Luiselli’s short reflection on her time volunteering with undocumented children from Central America in New York, Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions (2017). In some ways it appears to extend the same first-person character and reads as memoir, but it is a fiction loosely based on Luiselli’s life experiences as a Mexican living in the US. Lost Children Archive is structured around a journey taken by the protagonist, her husband, and their two young children from New York through the southern states of the US. It is a novel of family, kinship, and adventure, that weaves through the protagonists preoccupation with the news about the perils faced by the migrant children from Central America, and her own uncertainty as to what she can do to help them. Formally innovative and highly affecting, Lost Children Archive is a powerful narrative capturing the personal and political challenges of living as a migrant in twenty-first century US.

Dr Niamh Thornton, Reader in Latin American Studies, University of Liverpool

Reading List

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2010. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Abingdon: Routledge.

Gurba, Myriam. 2017. Mean. Minneapolis and Brooklyn: Coffee House Press.

Luiselli, Valeria. 2017. Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions. Minneapolis and Brooklyn: Coffee House Press.

Luiselli, Valeria. 2020. Lost Children Archive. New York: Vintage.

Sánchez, Erika L. 2019. I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter. New York: Ember.

‘Shadowland’ – The story of Germany, told by its prisoners

Sarah Colvin introduces her new book on Germany from the inside

It will be one of the hardest days in your life, and you’ll never, ever forget those prison gates closing behind you.[i]

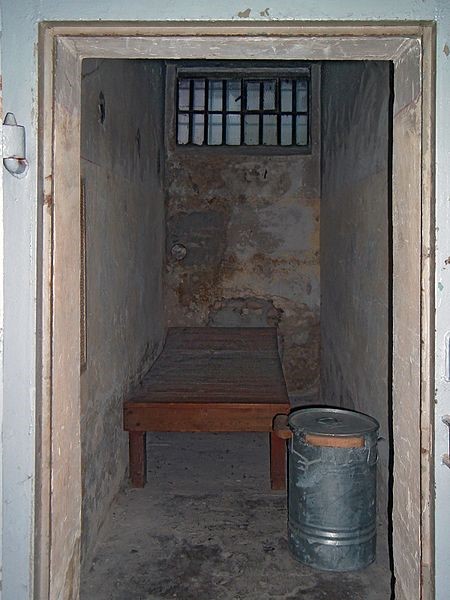

I get out of the bus and see grey walls, barbed wire, doors made of steel. They take us to a cell and our names are called. It’s a while before they call me. I feel terrible, and the lump in my throat just gets bigger and bigger. Then it’s my turn. … I have to get undressed and my clothes get searched again. I have to bend over and pull my arse cheeks apart. I have to lift my testicles. I have to pull my toes apart … The number of my cell is 172, my prison number is 357/9. The officer just unlocks and does the checklist with me; nothing is broken and everything is there. Then he locks the door behind me. My first moment alone in a cell.[ii]

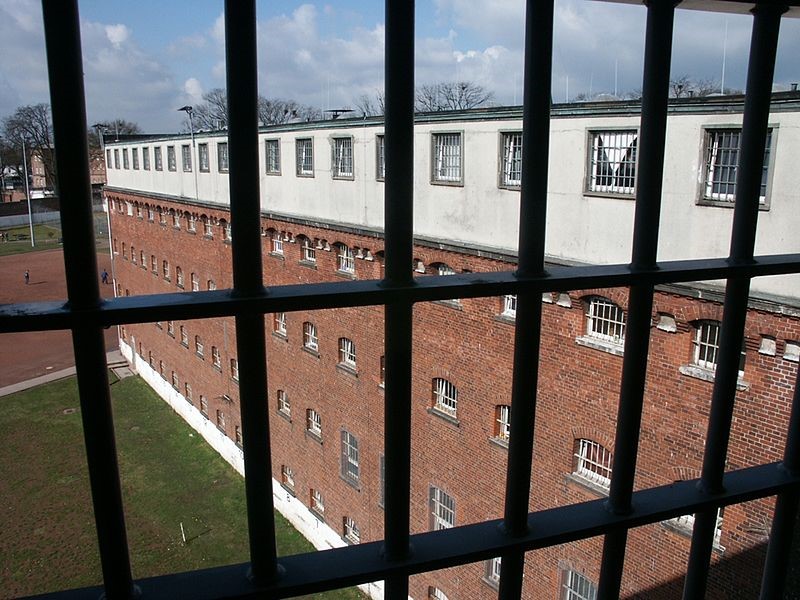

The world’s prison population is growing faster than its general population, and prisons are full to bursting. In overcrowded and understaffed conditions violence levels are high. Detention is hugely expensive while its efficacy is very much in doubt – “people just learn to be better criminals in here” wrote Oliver from a German prison in 2016. In 2019 Germany’s prisons were 88 percent full, with severe overcrowding reported in some.

It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.

(Nelson Mandela)

Shadowland tells the story of Germany after 1945 in the words of its prisoners. That is a different and often shocking perspective on the nation – but it’s worth bearing in mind that Germany locks up fewer people, in generally better conditions and with better human rights, than the UK or US. At 140 per 100,000 the incarceration rate in England and Wales is approaching double Germany’s rate of 78 per 100,000; the US tops the world charts with 655 per 100,000. German nationals in prison have the right to vote, unlike prisoners in the US or UK. Recently a prisoner union (Gefangenengewerkschaft) was founded in a Berlin prison, focused on issues like pay and pensions. Germany offers better provision for families and for women with children, and there is a glimmering awareness of the needs of transgender people.

CC-BY-SA

The story begins in 1945, in a country on the edge of social and legal collapse. Orphaned and abandoned children slept in the woods, stealing and scavenging, often laying the foundations for a “criminal career”. In the eastern zone hundreds of thousands froze, starved or died in Soviet Special Camps, or were deported for hard labour to the USSR. The GDR created interrogation centres for its secret police, the Stasi, and torture facilities including the notorious water cells and standing cells. Outside, in what some called the “big prison” of the walled-in nation, most people preferred not to know what was going on. Meanwhile in West Germany denazification was a challenge (“the prison guards were old Nazis,” one man reported – “a real truncheon brigade”), and a long-awaited grand prison reform erected, in the words of a prisoner, “little asbestos walls in Hell”.[iii]

Prison is a microcosm, a reflection of life outside.

(Peter Zingler, scriptwriter and former prisoner, 2016)

Over and again, stories from the inside say that prison is society’s mirror, and society needs to take a long, hard look at itself. In the 1960s a West German prisoner wrote a letter to the state prosecutor describing the case of X, a young offender who grew up in care homes and borstals and “continued his education” in prison. The courts declared X asocial and a psychopath. Not only the justice system, the letter points out, but every single person who had contact with the boy in an official capacity since he was fourteen years old must, therefore, have “failed disgracefully” – “don’t anyone tell me that it was all the boy’s fault.” Another writer makes the same point. “Yes, we’re abandoned, we’re excluded from human society. But do we really bear the entire burden of guilt?” “When you look at us it’s like you’re looking into a mirror of your society”, a man serving life told journalists who interviewed him. “Dear God, where do you think we come from? We’re not from the moon, we come straight out of your damn society and everything we carry with us in here we learned out there”.[iv]

Mirrors don’t always show things it’s comfortable to see. The gentle “Ostalgia” some feel for the East German past isn’t shared by anyone who spent time in an East German prison. Going to prison in West Germany was no walk in the park, but the exacerbated hiddenness of penal practices in the East, and the authoritarian bent of the state, made for peculiarly cruel and arbitrary conditions. Those who experienced them write of being “hung up” on cell bars or chained to the floor, or of prisoners left standing in their own urine or faeces in a flooded water cell. Prison in the GDR meant being denied access to the criminal or penal codes of the state that had incarcerated you, and permanent unclarity about what the future held. You might be released; equally you might find yourself in long-term solitary without a reason given. Erich Loest was held for 7½ years in East Germany’s notorious Bautzen II, 2½ of them in gruelling solitary, without ever being told which paragraph he had been convicted under. The Black East German writer, André Baganz, spent 5 years in solitary confinement. When he asked why his captors told him they did not need a reason.

I swore to myself that one day I would write down everything I was experiencing and publish it.

(Birgit Schlicke, on imprisonment in the GDR in 1988)

In 1990, German unification offered the opportunity for a new start. “The future’s in the air – I can feel it everywhere, blowing with the wind of change” sang The Scorpions. But how strongly did the wind of change blow on the inside? “It can’t be true that there are prison conditions like this in Germany”, wrote Katharina from a German prison in 2010, observing rats and broken windows in midwinter. She hated using the lavatory “because everyone had a perfect view of it from their bed.” A national report in 2017 complained that many shared cells still had no wall or partition dividing the washing facilities and WC from the main living space. “This kind of imprisonment ought to be a thing of the past”, wrote Martin Finke, after drinking his own urine in a punishment cell when his pleas for water were ignored.[v]

One woman was crying. They told her to stop or they would put her in the bunker. She was next to me in my cell. She didn’t stop crying and two officers came with a bucket of ice-cold water. They poured it over her and then put her in the bunker.

(Rita, FRG 2018)

Numerous present-day stories describe sometimes fatal instances of violence and medical neglect: “surviving your time in prison is a constant fear and worry”.[vi] And still, the cultural mainstream struggles to hear stories from the prison. Prisoners suffer from what Miranda Fricker calls a credibility deficit – as a radically marginalized group of people who often come to prison from already-marginalized communities, prisoners find that their stories are at best inaudible to those outside, at worst dismissed and disbelieved.

The people out there, on the other side of the wall, never believe a word we say.

(Peter Jörnschmidt, FRG 1972)

And still, for people in prison, one way of surviving incarceration is to write. “Writing can take you to freedom,” declared Peter Feraru – “the opportunity writing offers to change something, both in yourself and in your environment, is huge.”[vii] It would be sentimental to claim that a prisoner’s-eye view is more authentic or true than other perspectives. But it is probably not less true. In a cultural context where some of the most prominent figures in society are daily exposed as shameless liars, the status of narratives from prisons is changing. H. Bruce Franklin, a professor of American literature, noticed with a little surprise in 2008 that the Heath anthology of American literature now included a section called “Prison Literature”. In the same year the Publications of the Modern Language Association of America made incarceration the topic of its May issue, and Texas Studies in Literature and Language produced a special issue on “Cultures of Detention” for the Fall. In 2015, the American Book Review issued a number on prison writing.

“Communicating your experience is resistance to a power that is taking away your subject status”, wrote Karin Amann, a former writer in prison and now a jury member for the Ingeborg Drewitz Prize, Germany’s most significant literary prize for prisoners. “All the pressure that built up inside me was released via my pen”. “I can trash the cell when I’m desperate,” explained Karlheinz Barwasser, “or I can give the screw or another prisoner a smack in the mouth. But all those explosions come from the same place as my explosions on paper”.[viii] Thomas Galli, a former prison governor and a patron of the Drewitz Prize, sees writing as the opposite of violence. “Anyone who hurts others or causes severe damage is dividing people, creating fissures, digging trenches, causing injury,” Galli writes. “Anyone who punishes another human being by incarcerating them is dividing people, creating fissures, digging trenches, causing injury”, he goes on. “Literature, by contrast, brings us together”.[ix]

Sarah Colvin, Schröder Professor of German and Fellow of Jesus College, University of Cambridge

[i] Dirk Glebe, Handbuch Knast und Strafvollzug. 2nd edition. Norderstedt 2011, 17.

[ii] Harald A. Dreßler, “betr.: alltagsrealität im knast”, in Ingeborg-Drewitz-Literaturpreis (ed.), Risse im Fegefeuer. Hagen 1989, 63-65.

[iii] Peter-Paul Zahl, “Der große Reso-Schwindel” in Karlheinz A. Barwasser (ed.), Schrei Deine Worte nicht in den Wind: Verständigungstexte von Inhaftierten, Tübingen 1982, 64-67 (64).

[iv] A.P. “Brief an den Staatsanwalt” in Birgitta Wolf (ed.), Die vierte Kaste: Junge Menschen im Gefängnis. Hamburg 1963, 144-49 (145-47); H., in Wolf (ed.), Die vierte Kaste, 274; Peter, in Klaus Antes et al. (eds), Lebenslänglich: Protokolle aus der Haft. Munich 1972, 84.

[v] Katharina, 116 and 119; Nationaler Stelle zur Verhütung von Folter 2017, 24; Markus Finke, “Arrest”, in Koch (ed.), Mit der Flaschenpost gegen einen Ozean: Briefe aus dem Knast. Münster 1998, 82-84 (83).

[vi] Anon., in Der Lichtblick 372 (2017), 17.

[vii] Peter Feraru, in Uta Klein and Helmut H. Koch (eds), Gefangenenliteratur. Hagen 1988, 118.

[viii] Karin Amann, “Eindrücke eines Jury-Mitglieds” in Ingeborg-Drewitz-Literaturpreis (ed.), Gestohlene Himmel: Widerstehen im Knast, Leipzig 1995, 12-15 (13); Karlheinz Barwasser, “Sich als starke Mauern begreifen” in Helmut H. Koch and Regine Lindtke (eds), Ungehörte Worte: Gefangene schreiben. Münster 1982, 107-11 (107-8).

[ix] Galli, “Von Mensch zu Mensch”, in Ingeborg-Drewitz-Literaturpreis (ed.), Begegnungen in der Welt des Widersinns, Zell/Mosel 2018, 9-12 (11).