Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Internment and refugee organisations in the Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Archive

The internment of nearly 30,000 of the 80,000 refugees from Nazi Europe in the UK in the summer of 1940 disrupted community organisations and the vital support networks which provided a measure of relief to the traumatised refugees. Austrian Jewish exile actors Martin Miller and Hanne Norbert were active in a number of these organisations, notably the Austrian exile theatre, the Laterndl. In this blogpost Miller Archivist Clare George looks at some of the records in their archive for evidence of how mass internment in the summer of 1940 affected such organisations.

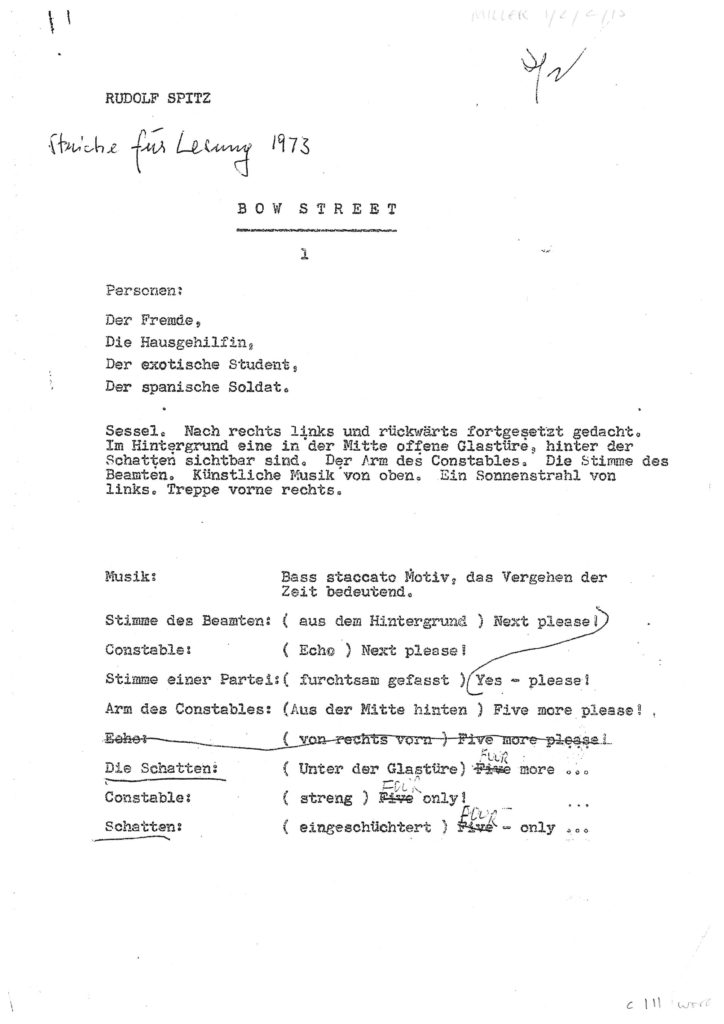

The Austrian exile theatre was established in the spring of 1939 with the aim of contributing to the fight against Nazism and in the first year of its existence it provided an opportunity for the refugee community to share stories and the experience of exile. The theatre reflected on the issue of hostility to the refugees in UK in the sketch ‘Bow Street’ by Rudolf Spitz, which was staged in the company’s first production, Unterwegs, in June 1939. Set in Bow Street Magistrates Court, the sketch saw the trial of three refugees being overseen by Judge Commonsense, General Bias and Mrs Charity. The Times described the sketch as the theatre’s ‘most ambitious piece, … which reflects upon the grim present’ and The Spectator reported that the sketch had ‘a real and unforced pathos that brought tears to the eyes of weaker members of the audience’. The scene appeared almost to anticipate the ‘enemy alien’ tribunals that would start a few months later, with the positive outcome of the trial and Mrs Charity’s triumph over General Bias perhaps reflecting the gratitude to the UK felt by many newly-arrived refugees in 1939.

This early sketch was in fact unusual in its focus, since the Laterndl players aimed their satire principally at Nazi leaders and developments in Austria and Germany. In March 1940, as the UK’s press was demanding the imprisonment of the refugees as ‘spies’ and ‘fifth columnists’, the company produced one of its most popular anti-Nazi shows, The Eternal Schwejk. In April 1940 the actors began rehearsals for a new production of Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper, and in early May the theatre group was confident enough of its future to plan the publication of a yearbook to mark the first anniversary of its existence. By the time the Dreigroschenoper opened in late May however, the mass arrests had begun, and the company struggled to keep up with the loss of the actors to the internment camps. When first one and then a second actor playing the role of Mackie Messer was interned, the challenge of finding a third was just about met but it was clear that the theatre would have to suspend its activities.

In August the remaining company members attempted to re-open the theatre. With the support of the Laterndl’s patrons, PEN members Janet Chance, Herman Ould and Storm Jameson, they wrote to the Advisory Council on Aliens at the Foreign Office for support. One of the Council’s functions was ‘to suggest measures to maintain morale for aliens in this country so as to bind them more closely to our common cause’. Pointing out that the theatre had been run ‘solely by exiled anti-Nazi writers and actors’, receiving ‘considerable publicity’ and ‘good audiences’, Laterndl writer Rudolf Spitz asked if the theatre could apply for ‘a grant to ensure its first expenses’. How the Council responded to the Council is not known, but in any case the theatre did not reopen at this point.

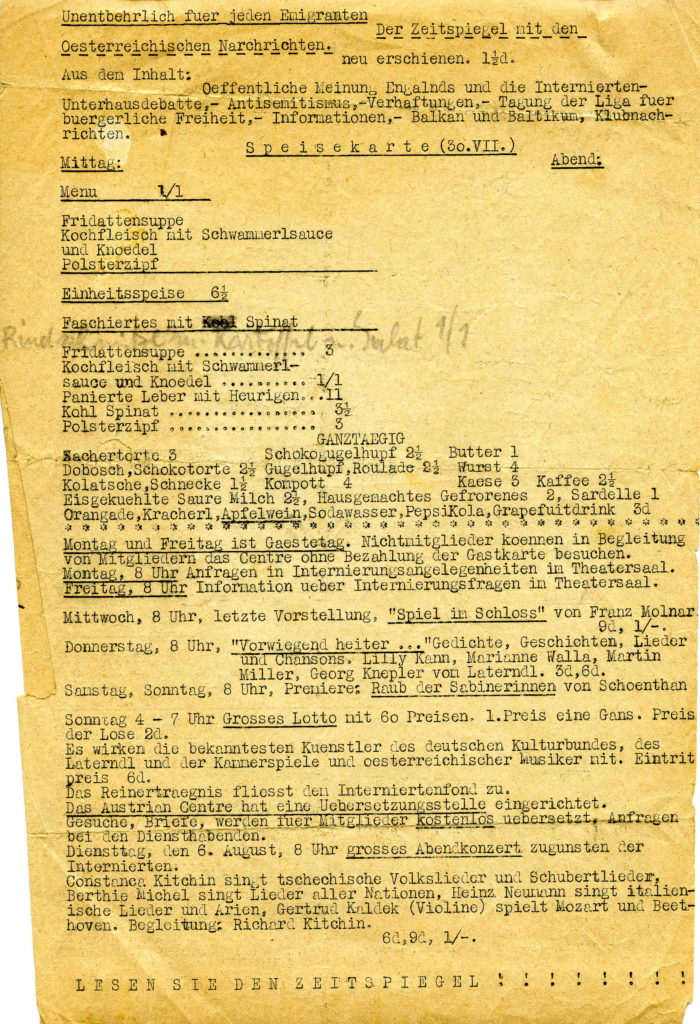

The Laterndl’s parent body, the Austrian Centre near Paddington, London, also came under severe strain through the crisis, with many of its staff and most of its members interned. The Centre had been established by Austrian Communist refugees in March 1939 and by 1940 it was the largest Austrian exile self-help organisation in the UK. This newssheet from 30 July 1940 documents some of the ways it responded proactively to the challenge of mass internment in support of the community. Meetings and information events were held twice weekly to provide support and practical help for those whose loved ones had been arrested. The Centre’s newspaper, the Zeitspiegel, led with articles on wider UK public opinion on internment and debates in the House of Commons.

The Centre also launched an entertainment programme of concerts and literary performance to raise funds for the internees. Some of the Laterndl actors who had not been interned contributed to the programme, amongst them Martin Miller. In a fascinating oral history interview carried out by Charmian Brinson in 1995 with Norbert (by then Hannah Norbert-Miller), the latter revealed that it was in fact Miller’s work at the Centre and the Laterndl which had indirectly enabled him to avoid internment in June 1940. Miller, who had been classed as Category C (no security risk) at a tribunal in October 1939, was then living in Putney in south west London. It was a considerable journey from there to both the Laterndl at Swiss Cottage and the Austrian Centre at Paddington, and to save on fares Miller would stay at work and sleep in the offices overnight. When the police came to arrest him early in the morning in June 1940, they were therefore met with the simple message that he was away from home, at which point they appear to have given up. Norbert-Miller commented that this was ‘a thing I just can’t understand. Instead of thinking this very suspicious, they just never bothered to find him. I used to meet him in Marble Arch, courting at 6 o’clock in the morning’.

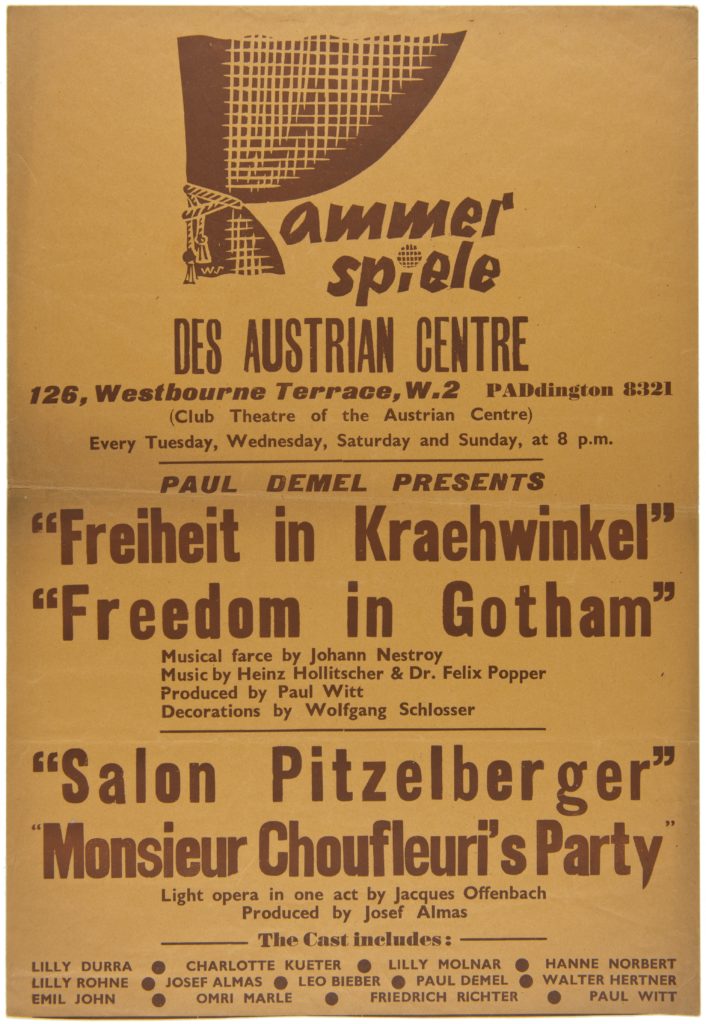

As well as the programme of weekly concerts and literary events for fund-raising at the Centre, space and support was also given to a new theatre group, the Kammerspiele des Austrian Centre. The group brought together actors from the Laterndl who had not been interned, including Hanne Norbert and Lilly Durra, with those in a similar position from the Free German League of Culture, which had also been forced to close. The Kammerspiele also involved a number of German-speaking refugee actors from Czechoslovakia, who were not under threat of mass internment since they were considered to be ‘friendly aliens’. Very few traces of this theatre company have survived but this poster shows that their productions included Nestroy’s Freiheit in Kraehwinkel and Offenbach’s Salon Pitzelberger. The company probably did not last more than a few months, however, and it was more than a year before the community could announce it had a fully functioning theatre again, with re-opening of the Laterndl in new premises in September 1941.

This blogpost draws on research by Professor Charmian Brinson and Professor Richard Dove into the archive of Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller. The archive was kindly deposited at the IMLR by the Millers’ son Daniel Miller in 2001 and is managed by Senate House Library on behalf of the Institute. Further information about the archive can be found here and an online catalogue of the archive can be found here.

Professor Brinson’s oral history interview with Hannah Norbert-Miller was carried out in 1995 as part of a series of interviews carried out by members of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies with German-speaking refugees from Nazi Europe. Further information about the interview is available here.

Read more Stories from the Exile Archives

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR.

Reading for the Everyday in Postwar French Fiction

David Ewing is a doctoral candidate in Modern French at the University of Cambridge. His research considers the relationship between everyday life and narrative fiction in postwar France.

A history of the everyday in modern European literature might begin with Baudelaire, who refused the Romantic flight from daily reality to the realm of the marvellous: by bringing thought to bear on poetry, the everyday could be made to eat away at itself, eventually yielding a marvellous truth that would cancel and replace it. Generations later, the Surrealists would find only new means to the same end: the dissolution of the ordinary into the extraordinary. Meanwhile, Flaubert, Baudelaire’s partner in prose, was to develop a style that could linger on the everyday, but less to celebrate its richness than to underscore its banality. More hospitable was Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), a work whose poly-ness (-phony, -rhythm, -valence, etc.) was able to transfigure – but not yet banish – the everyday. The view from the mid-twentieth century, however, was that literature had been unable to come good on the possibilities opened by Joyce. If Claude Simon’s La Route des Flandres (The Flanders Road, 1960) bears notable similarities to Joyce’s masterpiece, it does not so much metamorphose the time, speech, and life of the everyday, as cool those aspects to a point of stasis; and if this process generates possibilities of its own, these have less to do with everyday reality than with literature as a project unto itself.

This is a caricature of the history of literature that underpins Henri Lefebvre’s formidable body of writings on everyday life. An abridged version of the story appeared in the first volume of his Critique de la vie quotidienne (Critique of Everyday Life, 1947); additional scenes are to be found in his primer of 1967, La Vie quotidienne dans le monde moderne (Everyday Life in the Modern World). In the latter work, Lefebvre asked what had changed between Ulysses and La Route des Flandres: the capacity of literature to transform everyday life through representational means, or everyday life as such? The answer, in short, was both, with the upshot that only critique could hope to grasp, and transform, the totality of the everyday. At least one facet of this argument – namely, that narrative fiction after modernism struggled to find a productive relationship with everyday life – has proven durable: in Modernism and the Ordinary (2009), Liesl Olson suggests that ‘theorists like Lefebvre begin to write about the everyday when it becomes a question of whether the novel or postmodern writing more generally can represent the everyday through the conventions of realism.’[1] But in what texts is such a crisis of representation most acutely posed, and what is offered as a way out? If it is not straightforwardly a flight from the everyday, what can the path of travel tell us about the potential of narrative fiction vis-à-vis everyday life?

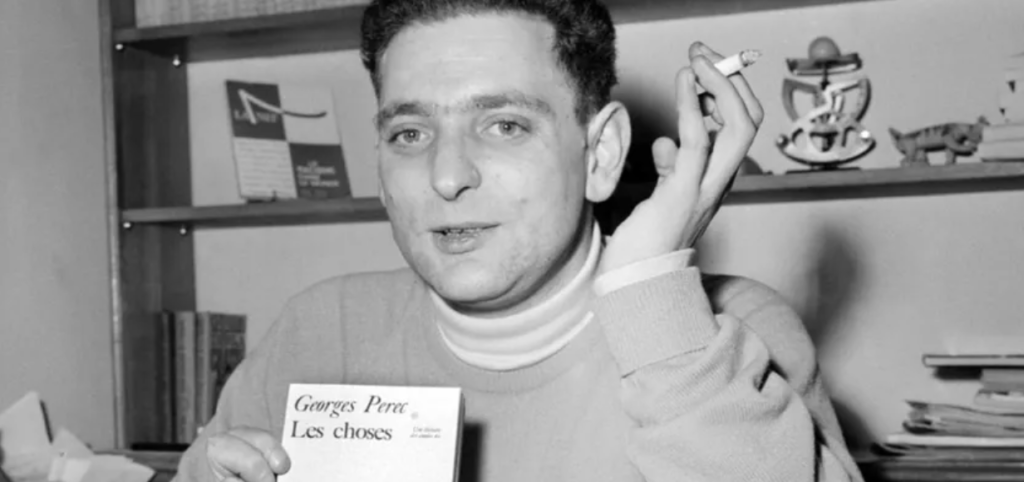

My research homes in on the relationship between ordinary experience and French narrative fiction in the period bookended by the publication of Lefebvre’s first volume of the Critique in 1947 and the appearance of its final instalment in 1981. In the thirty or so years following the Second World War, writers such as Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Sarraute, Michel Butor, and Georges Perec, whose names are often found in parentheses accompanying an invocation of le nouveau roman (and, with it, rather un-ordinary connotations of abstraction, formalism, and elitism), were seeking to restage the encounter between the novelistic form and experience. To be sure, the category of experience is capacious; only with some force can it be reduced to the everyday. But in taking a corpus of texts written in the wake of literary modernism and plotting the movements staged between ordinary experience and its counterpoints (extraordinary experience, the event, death, life grasped in the singular, and so on), it is possible to generate a set of ideal types that represent the possibilities opened by experimental fiction for dealing with – and, ultimately, vesting value in – the everyday. This way of reading for the everyday not only allows us to ask how successfully such texts worked on the everyday lives of their original readers; it also allows us to rethink, or reperceive, the phenomenological aspects of the everyday through some of the most daring apprehensions of experience, space, and time in the history of the novel.

David Ewing, doctoral candidate at the University of Cambridge

[1] Liesl Olson, Modernism and the Ordinary (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 14.

A Museum for Me | Un Museo Para Mi

On 10 May 2020, a unique virtual museum for English and Spanish-speaking audiences was launched at the University of Liverpool as part of the Culture Unconfined digital festival and AHRC-funded MVR Research project, led by Professor Claire Taylor.

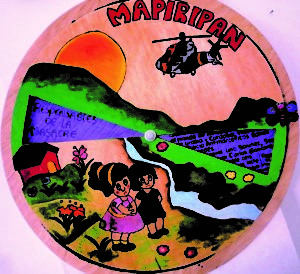

“A Museum for Me | Un Museo Para Mí” creates a space for survivors and exiles of the Colombian armed conflict to share stories, and helps make visible the work of the Colombian Truth Commission (la Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición) with members of the Colombian diaspora.

Dr Cherilyn Elston, Lecturer in Latin American Cultural Studies at the University of Reading, and a member of the UK and Ireland Hub in support of the Colombian Truth Commission,[1] interviews Professor Taylor and Dr Lucia Brandi (MVR project), about this exciting new initiative.

Cherilyn: First can you just briefly tell us who or what the MVR project is?

Claire: MVR stands for Memory, Victims, and Representations of the armed conflict in Colombia – it’s an AHRC project led by Liverpool with research partners in Colombia and the UK. We’re just drawing to a close, in terms of the initial investigations, but entering a really exciting new phase, focusing on translating MVR findings into specific actions with lasting impact. For example, we are working with community actors to address the invisibility or silencing of particular social groups within the conflict, and gender-blind or identity-blind representations of violence. A Museum for Me is one of the legacies of the MVR project, thanks to the UK’s Global Challenges fund (GCRF) and the Museo Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá.

Cherilyn: Addressing the invisibility of particular social groups within the conflict is hugely important, and chimes with my own research on gender and the armed conflict in Colombia, as well as my work with Colombian migrants and exiles living abroad who have been historically silenced in peacebuilding processes and mainstream narratives of the conflict. How would you describe A Museum for Me?

Lucia: A Museum for Me began life as a very simple idea and single product- we worked with the designer at the Museo Nacional de Colombia, Camilo Sánchez, to create craft kits for building your own mini-museum. We ran workshops for adults and children in the UK and Colombia, in which participants created mini-museums and placed objects and exhibits inside that tell their own stories. The workshops were really popular, and some of the creations were even displayed at the Tate Liverpool and the Museo Nacional de Colombia for our inaugural exhibition on 25 February this year. The workshops seem to function on different levels for different participants – for embedding memory, for consciousness-raising, honouring loved ones, as focus groups, inter-generational communication, or for just reflecting on what is important to you – the more the museum kits are used, the more functions they reveal. Now we have a whole range of products, but I think the most meaningful activities are always the simplest.

Cherilyn: Why the move to a virtual museum? Is that just a response to lockdown?

Lucia: Yes and no – I think we were always planning a digital platform for the project, but obviously lockdown has accelerated our actions. In fact, I think it has led us to a whole new layer of community engagement that complements face to face workshops. A Museum for Me is no longer a set activity or product, but rather it exists as a nexus of virtual and physical spaces where victims, survivors, exiles, artists, human rights activists, researchers, museologists and NGOs can take centre-stage. People use the platform to communicate personal memories or relate the testimonies of others, clarify truths, showcase their social action, and intervene directly in the representation and discourses around their person and stories. These stories come in myriad formats, from plain narrative and text, to music, poetry, dance, visual arts – in essence, the character of A Museum for Me has been determined by its contributors, who include the UK Representative of the Colombian Truth Commission, and the many volunteers of the UK and Ireland Hub, who are reaching out to exiles and gathering testimonies as part of the peace process. For example, A Museum for Me supported the Commission’s efforts to include LGBT voices in analyses of truth, recognition and exile. And I would add that the platform is not delimited or exclusive – for example, we just recently saw in Refugee Week how Mujer Diáspora (a UK-based network of exiled Colombian women, which I know you are closely involved in) created content in English in order to connect with non-Spanish-speaking audiences, and celebrate an opportunity for making links between all survivors of war and conflict.

We’ve also had expressions of interest in our content from museums outside of Colombia, in other Latin American countries, which shows how the activities speak to many other national contexts. This energy and creativity are the momentum behind the site.

Cherilyn: You mention English-speaking audiences – so is most of the content in English?

Lucia: Absolutely not, in fact the site is a good example of the Spanish/English translanguaging practices of the diaspora, who move between codes freely according to the source / target / function / context of a speech act. At the same time, there is more than enough content in each language to suit monolingual English or Spanish-speaking audiences. I do think the language choices people make tells us something about how the platform is viewed and could be used in the future, within and beyond specific communities. In fact, all the materials are still available online for public use, and we’d very much encourage people to download the packs and create their own museums and other kits.

Cherilyn: As a collaborator with the UK Hub in support of the Colombian Truth Commission, I know that both the act of sharing, and of listening to, personal testimonies of human rights abuse, is highly sensitive terrain and potentially very distressing – why would anyone choose to contribute their story to A Museum for Me, or for that matter, choose to visit?

Lucia Yes that’s entirely true, but for me, I think it’s because we are living through an historic moment – the Colombian Truth Commission is starting to wind-up its reception of testimonies and getting ready to produce its final report – people know this opportunity will not come around again, and are more determined than ever that truths, which they have held close over decades, should reach the public domain, and that the fate of loved ones should be brought to light. That’s why the activism of the Colombian diaspora, and groups such as Mujer Diáspora has been so central to the shape of the Truth Commission, and it’s why A Museum for Me is so timely. It’s no contradiction to also describe A Museum for Me as joyous and inspiring – profound depths of grief are matched only by the heights of energy and creativity of contributors, and an unshakeable commitment to peace, well-being, and non-violence. It is actually a very life-affirming and uplifting experience, and an important reminder that violence is not the last word in the Colombian story.

Dr Lucia Brandi, Research Associate, Impact and Engagement, AHRC project ‘Memory, Victims, and Representation of the Colombian Conflict’, University of Liverpool

[1] The UK and Ireland Hub in support the Colombian Truth Commission was created to fulfil the mechanisms for truth, reparation and recognition of victims agreed in the peace accords. Made up of individuals and organisations from the Colombian diaspora and civil society, its members included trained interviewers, who take testimonies for the Truth Commission. Please contact nodoreinounidoeirlanda@gmail.com for more information.

The Irish in South America – Stories from Statues

Ciaran Higgins discusses the role of Irish people in South America

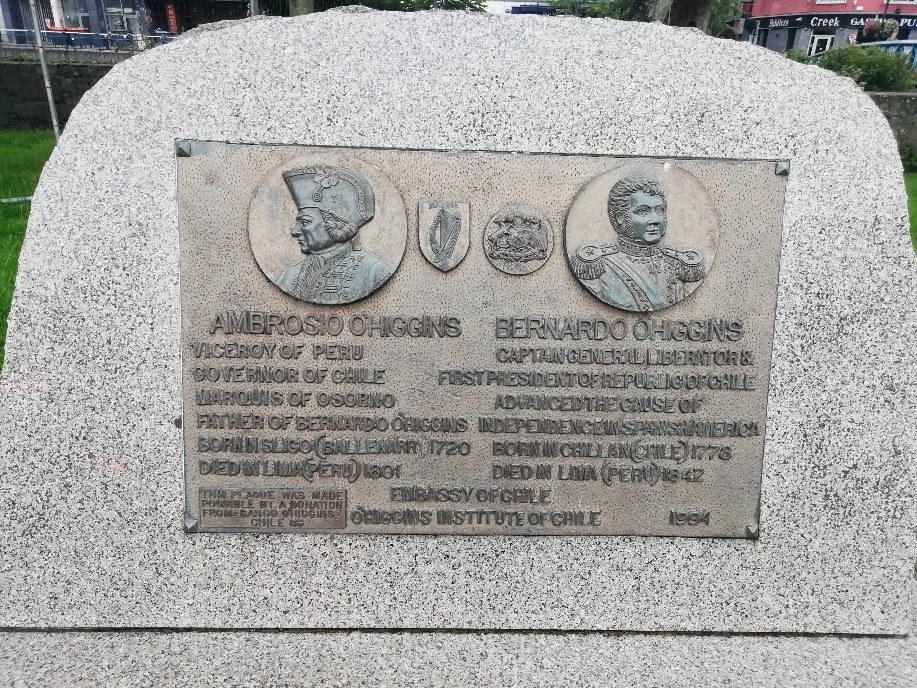

The photo above is of a plaque in Sligo, Ireland, commemorating a famous nationalist, a man who personally took up arms and overcame a large empire. His exploits led to streets and squares named in his honour, appearing on coins and stamps, there is even a football team that bears his name. It commemorates Bernardo O’Higgins, a man who made his name in South America, not in Ireland. As the first leader of an Independent Chile, his legacy is widely recognised there, as well as in Peru for similar revolutionary activities. He appears here alongside his father, Ambrosio O’Higgins, who originally hailed from Sligo, but rose through the ranks to become a leading official in Spanish South America.

Seeing this plaque again made me think about it in relation to the statues protests, attitudes towards historical figures and how they are commemorated. The O’Higgins duo achieved a lot, but they are stuck in an obscure spot in a Council car park. It was a gift from a bank in Chile, erected in the 1990’s. It sums up to me an overlooked history of the role of the Irish (and British) in South America. There are better memorials to Bernardo O’Higgins, one in Dublin and another at Richmond in London where he lived as a young man, but he is rarely noted in this part of the world.

Admiral William Brown, another remarkable figure who emigrated from the West of Ireland, ended up in charge of the Argentine navy. He is acknowledged by a worthy, if rather stern, bronze statue in Foxford, Co Mayo and one of more recent vintage in Dublin. These were also all gifts from South America.

Daniel O’Leary, a Corkman went to Venezuela in the early 1800s with thousands of British military volunteers fighting in the independence campaigns. He learned Spanish and became aide de camp to Simón Bolívar, later documenting the life of this seminal figure using first hand documents he preserved. In 2010 a well crafted bust of O’Leary was erected in a park in Cork city, and as recently as 2019 a plaque marking his birthplace was unveiled.

I once met a man who was part of a Uruguayan rugby team who survived a plane crash in the Andes in the 1970s and who ate the remains of their perished comrades to stay alive. He was an alumni of the Stella Maris school in Montevideo, founded by Irish Christian brothers in the 1950s, a school that contributed greatly to the development of Rugby in Uruguay. I was unaware of this connection until he pointed out the Shamrock on his old school tie and explained that historical link.

The Irish diaspora in the Anglo Saxon world is well documented and celebrated, but their involvement in non-English speaking societies less so. If the son of an Irishman had become the first leader of Canada I am pretty sure we would know a lot more about him. This blind spot can be down to the sheer weight of numbers that ended up in North America, but language and cultural memory must play its part. I can’t think of a traditional Irish song that recounts these Latin American stories.

In the English speaking world, it was easier to relocate, fit in, but also keep that contact with the Old World. Stepping outside that, into countries with a different language and ways of doing things to home, made them less visible, part of a distant ‘other’ world. Among my own ancestors, there was a history of emigration to the US, and I am still in touch with their descendants today. There is a family story of a Great, Great Uncle who made the move to Central America, and was never heard of again. He disappeared into that ‘other’ world.

There have been attempts to raise awareness of the history of the Irish in South and Central America, including exhibitions in 2016 and 2017. It is a worthy initiative. As the interest in learning the Spanish language increases in the UK and Ireland, perhaps we will re-evaluate historic connections with Latin America. The Council in Sligo are currently renovating the car park. I will be curious to see what becomes of the monument to a decisive figure in South American history.

Ciaran Higgins is Communications Officer for the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Open World Research Initiative

Stories from the Exile Archives: Records of Internment Camp Cultural Activities in the Papers of Arnold Gerstle

Many of the German-speaking refugees interned as ‘enemy aliens’ during the Second World War had backgrounds in the arts, and cultural endeavour flourished in the Isle of Man internment camps. In this blog post, Miller Archivist Clare George looks at the records of some of those activities in the papers of Arnold Gerstle, a Jewish refugee who was interned in Mooragh Alien Internment Camp near Ramsey on the Isle of Man in May 1940.

Gerstle was born in 1893 in Ichenhausen near Ulm in Bavaria, a village of around 2,700 inhabitants with a Jewish community of 300. In 1925 he married Henrietta Urnstein, born in Hesse in 1893 and also of Jewish heritage, and after the Nazis came to power the couple fled to the UK. In 1939 they moved to Tyneside in the UK to take advantage of the government scheme supporting refugees to establish businesses in areas of high unemployment. Together with fellow refugees, brothers Josef and Michael Mayer, Gerstle set up a manufacturing company in Team Valley, Gateshead, initially producing manicure and brush sets but later expanding into sports bags and children’s toys.

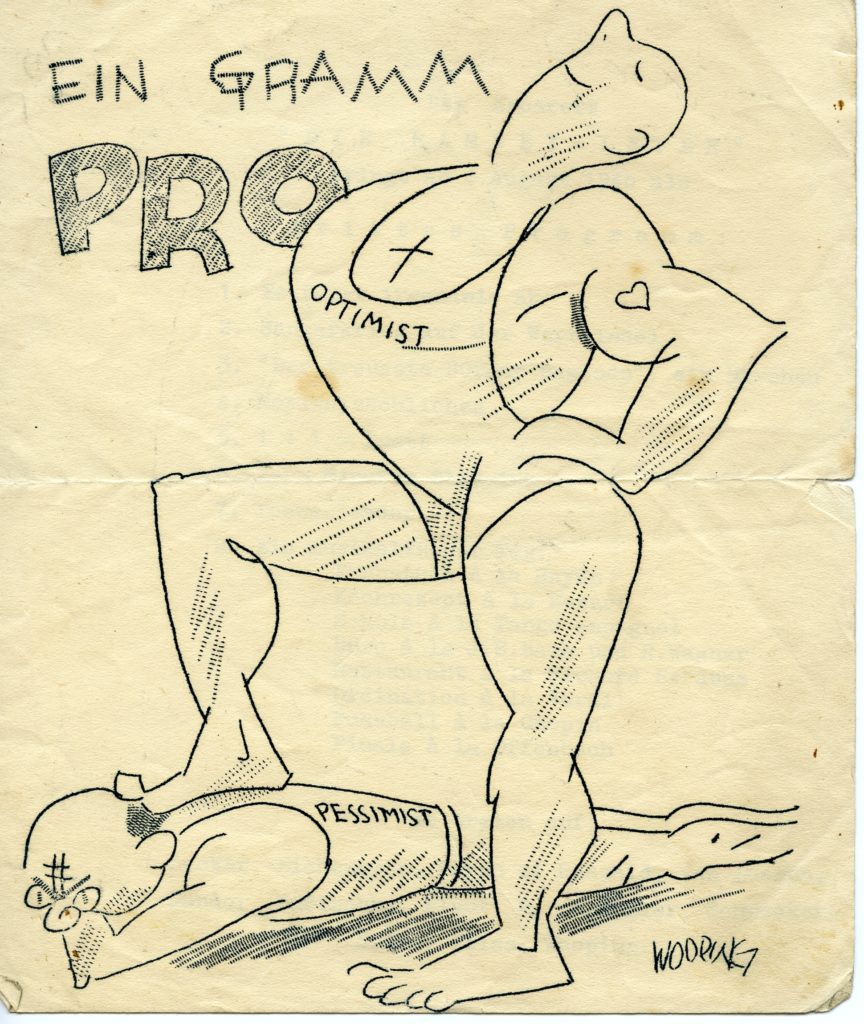

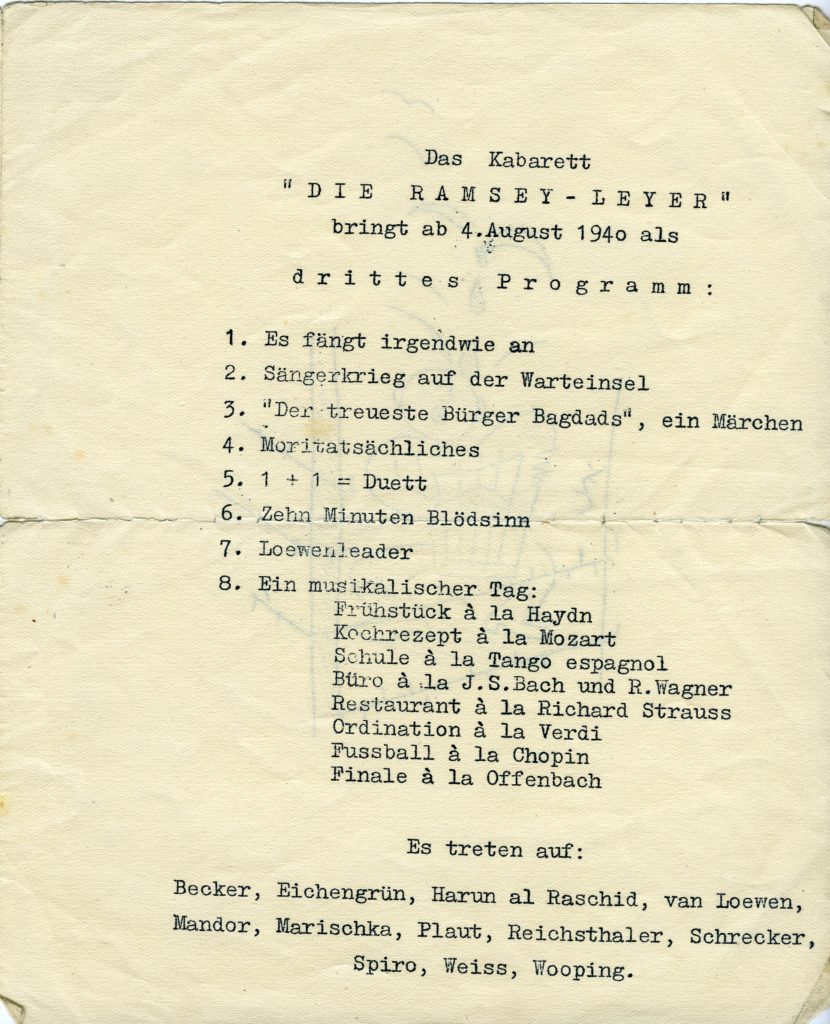

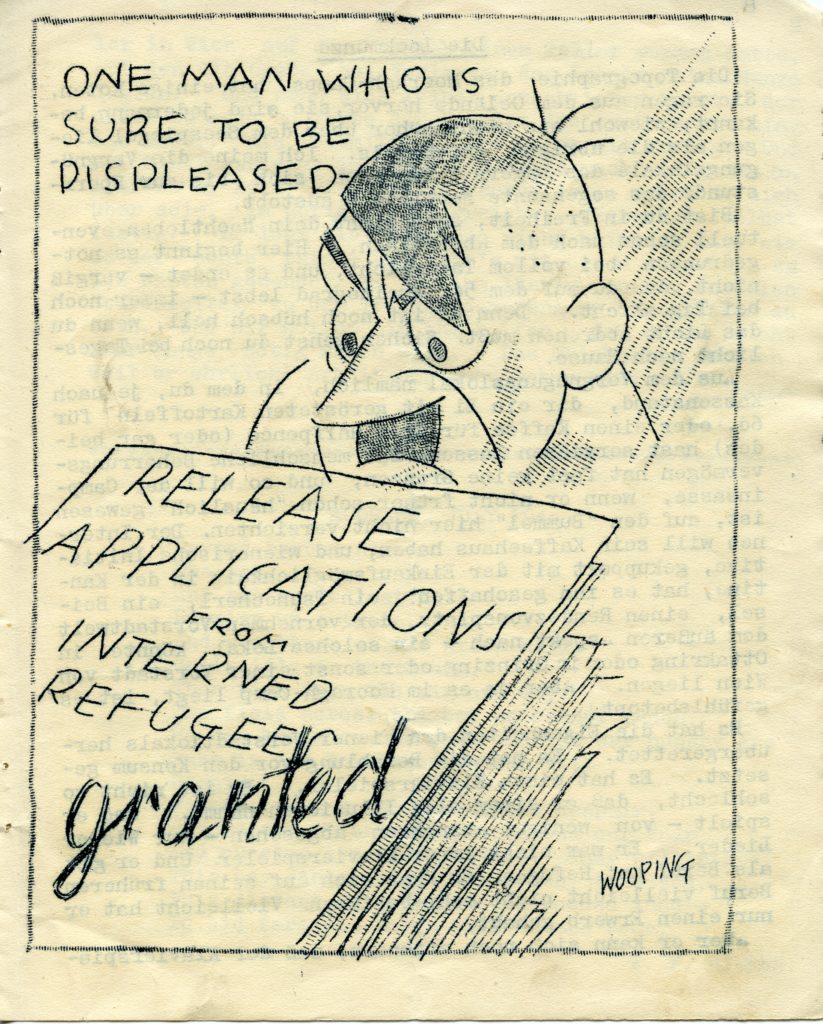

Gerstle was one of the first internees at Mooragh when it opened on 27 May 1940, the first internment camp on the Isle of Man. At its peak the camp held 2,900 internees, with whom theatre productions were immensely popular, though sadly relatively few records of these activities have survived. Whether Gerstle himself took an active role in them is not known, but in any case we know that he took the trouble to retain amongst his possessions one of the now rare theatre programmes designed by cartoonist Willi Wolpe (‘Wooping’) for the third Kabarett production by the Ramsey-Leyer, staged in August 1940.

Many of the eleven members of the Ramsey-Leyer were highly experienced theatre performers. Wolpe had co-directed the first cabaret by the Free German League of Culture, ‘Going – Going – Gong’, in London in July 1939. Franz Marischka and Josef Plaut were professional actors, and Fritz Schrecker was also an experienced actor who had worked in political cabaret in Vienna until 1938 and co-founded the Austrian exile theatre, the Laterndl, in London in 1939. Another performer listed is Harun al Rashid, an in-joke whose reference is now sadly lost (at least to the present writer, though she would be delighted to hear if anyone has any insights into this!).

The programme gives few details of the individual items performed, so we can only guess from the titles that some may have been written or adapted in the camp, like the ‘Saengerkrieg auf der Warteinsel’. Others we know were taken directly from Austrian political cabaret and had been brought to the UK by exiles and reperformed in London. The humorous songs collectively titled ‘Ein musikalischer Tag’ were written in Vienna by Hans Weigel and Herbert Zapper, and had formed the finale to the Laterndl’s first production in London, Unterwegs, in the summer of 1939. The third item on the programme, Der treuste Bürger Bagdads was a short play by Jura Soyfer, a young left-wing cabaret writer who was imprisoned by the Nazis in Dachau and had died in Buchenwald in February 1939. Written as a topical satire for performance in Vienna in 1937 and reperformed at the Laterndl in early 1940, the play’s production in internment in the UK would surely have stirred strong emotions and heightened the refugees’ sense of injustice at their situation.

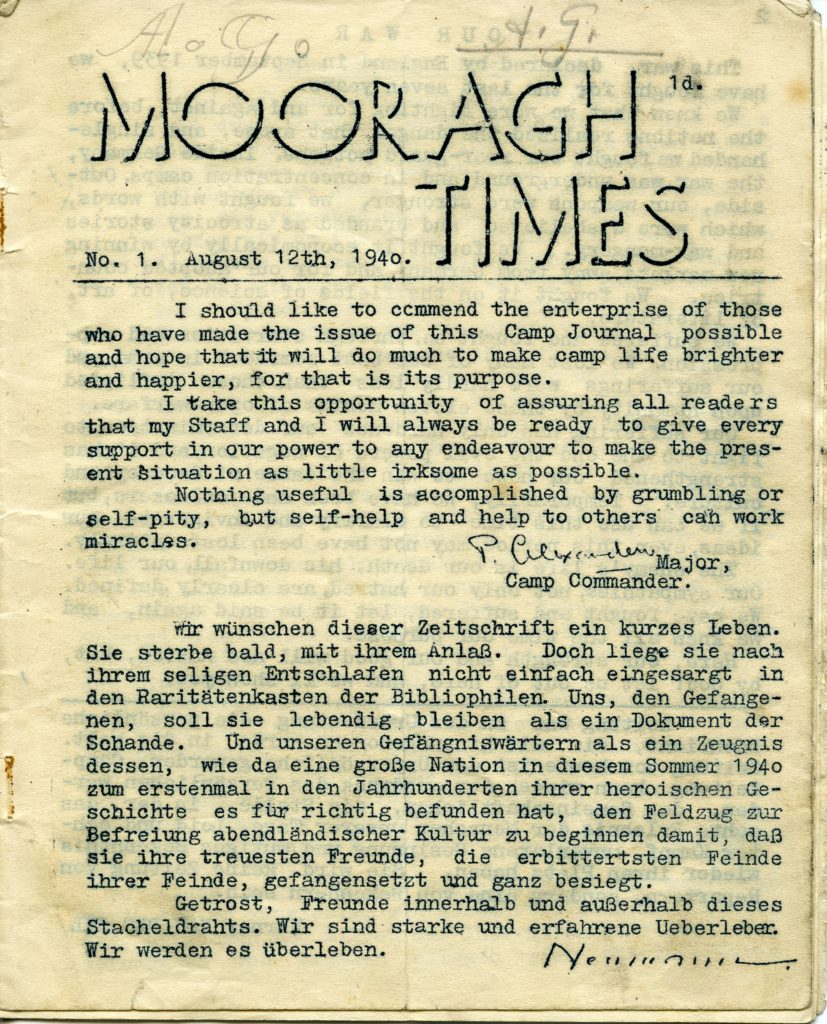

Gerstle’s papers also include the only issue of the predominantly German language internee camp newspaper to have been produced: the Mooragh Times dated 12 August 1940. The 16-page paper features stories, poetry and commentary on camp life and the wider situation of the refugees, clearly demonstrating the self-confidence and ambition of the editors, who included writer Robert Neumann and Rabbi Werner van der Zyl. Several articles reflect on the guidelines on the release of internees published in a government White Paper on 1 August. One internee, Friedrich Steiner, contributed a satirical news report about the discovery of a previously unknown human-like species on the Isle of Man called ‘Interniten’, who busied themselves with writing application forms and adhered to a new religious faith in the mysterious notion of ‘release’. Cartoons with a clear message on the policy of internment, written in English to reach the British authorities, were supplied by Wolpe (who later worked on propaganda art for the Ministry of Information – see https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/theartofwar/artists/wooping.htm).

The Camp Commander, Major P. Alexander, used his foreword to the journal to praise the internees’ enterprise in producing it. After the event however, he concluded that it was too critical of the British government’s policy of mass internment, and permission to publish further editions was withdrawn. He advised that the editorial team should instead write something to boost morale and make people laugh. Soon afterwards rules for camp journals were drawn up stating that ‘such journals should be purely for the purpose of brightening camp life and are not permitted as vehicles for complaints and political propaganda of any sort’.

Fortunately these fascinating records of camp life were retained by Gerstle when he was released from the Isle of Man in late summer 1940, and later in the war, when he and his business partners were forced to move their business to Newcastle, the papers went with him. Gerstle gained British citizenship in 1947 and remained in Newcastle until his death in 1958. His wife, Henrietta, died in Israel in 1974. Their papers were kindly donated to the Institute of Germanic Studies by the Gerstles’ son, Mr Jacob Gerstle, in 1998.

This blogpost draws on Jennifer Taylor’s ‘”Something to make people laugh?”: Political Content in the Isle of Man Internment Camp Journals, July-October 1940’ in ‘Totally Un-English?’: Britain’s Internment of ‘Enemy Aliens’ in Two World Wars (2005).

Read more Stories from the Exile Archives

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR.