Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Languages of Disease in the Contemporary Francophone World

Steven Wilson reports on the conference Languages of Disease in the Contemporary Francophone World, held on 19 February 2021

Building on recent studies into the language used to represent disease in modern metropolitan France, Languages of Disease in the Contemporary Francophone World, supported by the IMLR’s Regional Conference Grant Scheme, aimed to widen the scope of enquiry into the geographical zones, cultural and political contexts of the broader francosphère. This is a community of countries and regions where many of the world’s recent pandemics, including Ebola, HIV/AIDS and cholera, have had devastating effects. The event was originally scheduled to take place at the University of Stirling in February 2021 but (and with inescapable irony) the coronavirus pandemic forced us to move it online. Hosting the workshop on Zoom nonetheless allowed almost forty delegates from across the world to join the discussion, while the backdrop of Covid-19 reminded us of the important role that modern languages have to play in representing and making sense of disease, one of the major global challenges of our time.

Taking account of current restrictions, the project organisers, Dr Hannah Grayson (University of Stirling) and Dr Steven Wilson (Queen’s University Belfast), decided to re-shape the event into a multifarious digital project comprising connected elements. An initial structured interview with Dr Charlotte Baker (Lancaster University), published on the IMLR website, was used to set out some of the context and key questions for participants to engage with. In the interview, Dr Baker gave details of the scope and impact of her work as Principal Investigator of the AHRC project ‘Alternative Explanations: Disability in African Contexts’. At the ensuing workshop, seven speakers, from the UK, France, Sweden, Finland and the USA, gave presentations, in French or English, following an opening keynote talk by Dr Éloïse Brezault (St. Lawrence University, New York State), entitled ‘Fantômes, intrus et épidémie dans Atlantique de Mati Diop ou comment repenser la crise migratoire à travers la maladie’. Dr Brezault’s keynote outlined many of the conceptual parameters of the project via an analysis of Diop’s critically acclaimed film.

The workshop was structured to allow for maximum discussion. Key areas to emerge included: the politics of epidemics across the francosphère; how the gender politics of francophone countries inflect the language used to describe disease; how disease is associated with practices and behaviours that mark cultural difference; and the duty of society when faced with disease. Presentations and discussion focused notably on what francophone literature, film, music, graphic art and testimony reveal about the role of language, genre and form in giving expression to diverse (including non-Western) experiences of disease. In a context where the global response to the coronavirus pandemic has been coordinated by the World Health Organisation, research presented at the workshop underscored the political, ethical and healthcare imperatives of avoiding approaches to disease characterised by universalism. Dr Baker, in the final section of the event, responded to the presentations and discussion, focusing on the crucial question of voice in representations of disease; she reminded us that, by paying attention to a multiplicity of voices – particularly from underrepresented groups – not only do we bring to the fore new languages of disease, but our research can play an important role in addressing health inequalities.

used to describe disease; how disease is associated with practices and behaviours that mark cultural difference; and the duty of society when faced with disease. Presentations and discussion focused notably on what francophone literature, film, music, graphic art and testimony reveal about the role of language, genre and form in giving expression to diverse (including non-Western) experiences of disease. In a context where the global response to the coronavirus pandemic has been coordinated by the World Health Organisation, research presented at the workshop underscored the political, ethical and healthcare imperatives of avoiding approaches to disease characterised by universalism. Dr Baker, in the final section of the event, responded to the presentations and discussion, focusing on the crucial question of voice in representations of disease; she reminded us that, by paying attention to a multiplicity of voices – particularly from underrepresented groups – not only do we bring to the fore new languages of disease, but our research can play an important role in addressing health inequalities.

We look forward to developing our reflections into a publication in the near future. In the meantime, the organisers would like to thank all participants for their contribution to the event, and express particular gratitude to Cathy Collins at the IMLR for her organisational support.

Dr Steven Wilson, Senior Lecturer in French Studies, Queen’s University Belfast

Words, Music and Marginalisation

Tom Smith (St Andrews) reports on this conference held in September, supported by the IMLR’s Regional Conference grant scheme

Words, Music and Marginalisation was initially scheduled to take place in person in September 2020 in St Andrews, hosted by the School of Modern Languages and our new Laidlaw Music Centre at the University. Due to the coronavirus outbreak and the subsequent lockdown and travel restrictions, the conference was moved online via Microsoft Teams. Although we were disappointed not to come together as a community in Scotland, this online solution enabled us to bring together more scholars and remove financial and travel barriers that early-career scholars and other colleagues might have faced.

As part of this switch to online delivery, I am very grateful to the Institute of Modern Languages Research for their support and patience as we adapted to the new situation. Our budget funded bursaries to enable access to the online conference for early career and postgraduate scholars.

In order to achieve the broadest reach within Modern Languages and across disciplines, I was delighted to secure the collaboration of the Forum of the International Association of Word and Music Studies (WMAF). The WMAF is a network of early- and mid-career scholars who meet regularly to explore the intersections between music, literature and contemporary theory. Working with the WMAF enabled the conference to support early career and postgraduate scholars as much as possible and to create a supportive environment where academic hierarchies were minimised.

The conference attracted 43 submissions for papers from scholars based across the world. In the end, we were able to accommodate 31 separate papers with 36 speakers. 70 people attended in total. Speakers and attendees joined us from Canada, China, Denmark, France, Germany, India, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, South Korea, Turkey, the UK and the USA. Within the UK, we placed a particular emphasis on encouraging attendees from Scotland and the North of England, with speakers or attendees from the Universities of Aberdeen, Durham, Edinburgh, Liverpool Hope, Manchester Metropolitan, Northumbria, St Andrews, from the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and from one (then) independent scholar in Aberdeenshire (since at the University of Reading).

The keynote lecture, ‘Listening at the Margins: Hearing Identity in Opera’ from Imani Danielle Mosley, Assistant Professor of Music and Music History at the University of Florida, provided a valuable theoretical reflection on the meaning of ‘marginalisation’ for artists who find themselves at the centre of the cultural canon. It was just a shame that her focus on Benjamin Britten’s operas Peter Grimes and Billy Budd could not be complemented on this occasion by the sound of the sea from the clifftops in St Andrews! The keynote lecture was extremely well received and attended by 70 people. It can be viewed on the University of St Andrews YouTube channel here:

Scholars gave papers on a range of literature, film and music, including German and French Studies, but also on Modern Languages research in a broader context: Cambodian/Khmer, Chinese, Hawaiian, Indian, Māori, Turkish. In line with our focus on marginalisation, several participants proposed to focus not only on European languages and cultures but on non-Western and Indigenous writing, film and music, facilitated by an overarching shared interest in music as a cultural phenomenon. To complement our virtual location in Scotland, a number of speakers focused on Scottish culture from postcolonial (Cherry and Hoene) and feminist (Haller-Shannon) perspectives, including Hoene’s engagement with Gaelic-language musical culture and ceòl mòr.

Throughout the conference, methods from Modern Languages, especially literary, film and cultural studies, proved invaluable tools in analysing, challenging and circumventing the discourses in musical and literary culture that marginalise certain people. Of particular note were the methodological reflections on trans scholarship and composition (Allphin), feminist history (Haller-Shannon) and film aesthetics (Hart and Ertan). The particularly high standard of methodological innovation by postgraduate students was impressive, and speaks to the vibrant state of the broader discipline. Queer studies and post- and decolonial methods were central to many papers, and there was a productive mix of historical work, close readings and theoretical analysis.

We were greatly inspired by the conference and look forward to building on the networks and relationships formed. Our thanks to the IMLR’s Regional Conference Grant scheme and for the Institute’s support throughout the process!

Dr Tom Smith, Lecturer in German, University of St Andrews

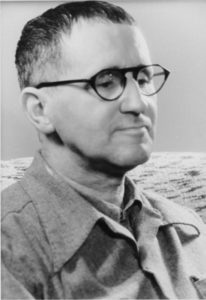

Widening the Circle. Thoughts on Brecht in Song workshop on Friday 18 September 2020, by Jack Tarlton and Stephen Sharkey

On Bertolt Brecht’s 123rd birthday, actor Jack Tarlton and playwright Stephen Sharkey look back at their Brecht in Song workshop held as part of the OWRI project in September.

Jack Tarlton: It started with the choice of books that I took into lockdown with me in March 2020, which included Bertolt Brecht’s Collected Plays: One. As I worked my way through the scabrous life of Baal in the first of the nine plays, I was struck by how the flint-edged street language of each scene seemed to trip itself up and become less clear and robust when it came to Baal’s songs. The imagery became cloudy and the forward momentum lost. I was intrigued by this, and although not a translator, lyricist or musician, I have been lucky in my role as an actor and director to have worked closely with those who are. I therefore thought it would be interesting to bring together a group of translators curious about the world of theatre and song, and five actor-singer-songwriters into a virtual workshop environment to see what would happen. Could they forge new versions of the songs of Brecht that lived and breathed as short dramatic performances?

First, though, I asked a previous collaborator, the playwright, adaptor and lyricist Stephen Sharkey – whose new version of Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui had been produced at the Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse – to join me in preparing the workshop. Together we researched Brecht’s life and plays and selected the five songs that we would rework. Five songs that each provided a specific idiosyncratic challenge – ‘Der Choral vom großen Baal’ from Baal, ‘Das Lied von Fluss der Dinge’ from Mann ist Mann, ‘Lied vom Flicken Und Vom Rock’ and ‘Bericht über den Tod eines Genossen’ from Die Mutter, and ‘Obacht, get Obacht!’ from Die Heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe. Supported and hosted by the Institute of Modern Languages Research, we were ready to see if the experiment would work.

On Friday 18 September we all gathered online, and after a session in which I shared my research on the importance of music and rhythm on the life, health and artistic development of the young Brecht, Stephen shared his own adaptation of ‘Das Lied vom Weib des Nazisoldaten’ from Schweyk im Zweiten Weltkrieg. The international group of translators gave their feedback to it, before the performers each took a verse and quickly collectively performed their own rough ‘n’ roll take on the song. After lunch I allocated a song and a team of translators to each performer, and they were off into their own break-out rooms to discover what they could create together.

My research had revealed that the adolescent Brecht had a close circle of friends and collaborators who would meet regularly in his attic to create verses, songs and short plays. As the workshop progressed it felt to me as though we were widening and diversifying that circle and making it our own. Brecht and his friends would then gather in a local tavern to share their work. Our tavern was the online gig that we held that night, where each song, reworked in a matter of hours and all truly alive and strikingly relevant were sung loud to an eager audience.

Below, published for the first time, are those five new versions of Brecht in song.

Stephen Sharkey: Translating the words of a song from one language to another is a devilishly difficult undertaking. How to convey the complexity and vivacity of great lyrics, the gut feeling here, the twisty-turny ironic word-play there, the explosive energy in another place? The linguistic fingerprint is impossible to replicate perfectly. But we have to try – few of us are able to read and fully appreciate songs, poetry, lyrics in a language foreign to us. For me as a playwright grappling with Brecht’s singular genius armed only with rudimentary German, existing translations and a decent dictionary, the Brecht In Song workshop was a revelation. The professional translators who Zoomed in from around the world – live from a cafe in Istanbul, or from a sitting room in Berlin – brought their urbane, incisive expertise to bear on the five Brecht songs we chose to explore.

First though, it was a real shot in the arm to have them read aloud and comment on my work-in-progress translation of ‘The Song of the Nazi Soldier’s Wife.’ Their enthusiasm was infectious, their rigour and focus impressive, and all these qualities were evident when they partnered up with our brilliant actor-musician-performers to make their own versions of the five songs.

After a whirlwind afternoon’s collaboration, an online audience gathered round their laptops to listen in to Aminita, Hannah, Jochebel, Michael and Robert, performing songs from four of Brecht’s plays. I had not expected to have quite so emotional a reaction to the pieces, but each had its own goad or sting or attack – Brecht (and collaborators) really knew how to land a line like a punch to the gut. It was a powerful reminder of how front-footed, scabrous, and vigorous is the voice of Bertolt Brecht in his plays and poems. I was moved by the voices, the physical presence of the singers, their gaze – even down a below-par internet connection. It was a painful reminder of what we’re all missing in 2020, how we need the shared experience, to be in rooms together. And how much we miss the theatrical room, in all its many forms.

Jack Tarlton is a Scottish actor, director and teacher. His stage work includes lead roles with the National Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company, Young Vic and the Royal Exchange, Manchester. Screen work includes The Imitation Game, 8 Days to the Moon and Back, Traces, Outlander, Doctor Who and The Genius of Mozart. He has taught Shakespeare and modern drama studies and adapting prose and translating for the stage at the University of London, University of Buenos Aires, Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Oxford University, East 15 Acting School and for The Old Vic and Out of Joint, and was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Modern Languages Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He can be found on Twitter @jacktarlton.

Stephen Sharkey has translated and adapted a wide variety of classic and classical stories for the stage, including works by Euripides, Aristophanes, Wilde, Defoe, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Dickens and Goncharov. His most recent work includes an adaptation of WHITE TEETH, Zadie Smith’s modern classic novel, in a major production at the Kiln Theatre by artistic director Indhu Rubasingham, a version of Tolstoy’s THE DEATH OF IVAN ILYICH for one actor, and INKHEART, adapted with Walter Meierjohann from the children’s novel by Cornelia Funke for Home, Manchester. His new translation of Brecht’s THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF ARTURO UI was commissioned and co-produced by Liverpool Everyman & Playhouse and Nottingham Playhouse. He can be found on Twitter @steshark.

Pious positions in Huguenot Memoirs

Nora Baker (Jesus College, Oxford): I am a second-year PhD student researching the self, humility, and cultural influences/pressures in memoirs written by Huguenot refugees in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, a law which had previously granted a certain degree of religious freedom in France. The Revocation effectively banned Protestantism in the kingdom, though policies aimed at eradicating French adherents to the reformed religion – known as ‘Huguenots’ – had been steadily increasing since the debut of the Sun King’s reign. 1681 saw the launch of the dragonnades, a practice which forced Huguenot families to harbour state soldiers in their homes, and provide for their feed. In return, these soldiers were instructed to harass their hosts and attempt to convert them to Catholicism.

Artist’s impression of Gamond from an English translation of her memoir, entitled Blanche Gamond: a French Protestant Heroine (1870)

In light of the oppressive measures taken by the Crown, it is not surprising that the late seventeenth century saw something of an exodus of Huguenots from France: an estimated 150,000-200,000 left for countries where they could practise their faith without interference. The road to exile was often fraught with danger, however – women who were caught risked being locked up in convents or prisons, and men could be condemned to servitude on the King’s galley ships. Many of those Huguenots who managed to safely settle aboard composed accounts describing their experiences of escape and confinement. My thesis explores the portraits that authors of such texts sought to craft of themselves and of their lives.

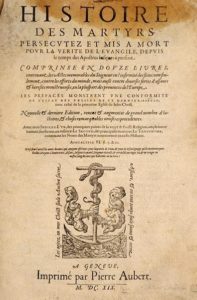

I look at the autobiographical writings of imprisoned women, enslaved men, and of refugees trying to put down roots in new lands. These authors may have experienced persecution in different ways, but they share an adherence to an established minority religious culture which informs both their narrative choices and their personal concerns. Formed amid the turmoil of the sixteenth-century civil wars, French Protestant writing counts the concept of martyrdom among its most prevalent topoi, and post-Revocation texts are no exception to this focus. Many authors appeal to their readers’ sympathies by showcasing how they have followed in the footsteps of models of piety documented in martyrological volumes. The writers I study did not actually face death for their faith – all eventually managed to escape France and penned their memoirs in exile – but we are often encouraged to interpret their stories, and the suffering depicted therein, as akin to the violence endured by believers who did die. Blanche Gamond, a young woman who was incarcerated in Grenoble and Valence, peppers her narrative with scenes that mirror or echo the actions of those souls who feature in the most popular French Protestant martyrology, Jean Crespin’s Histoire des Martyrs.

Title page of the 1619 edition of the Histoire des Martyrs (continued after Crespin’s death by Simon Goulart)

Though the last edition of Crespin’s edition was published in 1619, it maintained its place as a treasured text for the Huguenot community into the dawn of the eighteenth century: memoirist Jean Migault recalls his wife taking comfort from the tome as she lay on her deathbed in 1683.[1] The cultural memory of persecution faced during the Wars of Religion helped Huguenots living under Louis XIV build a framework to understand suffering in their own time: pain was a virtuous thing, a sign of God’s favour, rather than of disgrace. Jean-François Bion, a convert to Protestantism after a posting as a galley chaplain, shows in his account of ship slaves that even new members of Huguenot society were wise to the value the community placed on victimhood. Conscious of his former association with the oppressor, Bion takes care to emphasize his presence among the enslaved, caring for their wounds, listening to their stories, receiving praise from them for his open-mindness even before his conversion. He symbolically lowers himself to their level and links his fate to theirs as he describes how his own clothes became infected with the same vermin that afflicted the slaves.[2] To the Early Modern French Protestant society, this humble status was much more honorable than the earthly glory available to Nicodemites.

[1] Migault, Jean, and Yves Krumenacker. Journal de Jean Migault, ou, malheurs d’une famille protestante du Poitou, 1682-1689. Les Éditions de Paris Max Chaleil, 2011, p. 50.

[2] Bion, Jean François, and Pierre M Conlon. Jean-François Bion et sa Relation des tourments soufferts par les forçats protestants. Librairie Droz, 1966, pp. 86-87.

Nora Baker, PhD student, University of Oxford

The Songs of Pedro Ximénez Abril y Tirado: Poetry and Art Music in Postcolonial Bolivia

John Sloboda reports on this online seminar held in September 2020, co-hosted by the Institute of Modern Languages Research and the Institute of Latin American Studies (School of Advanced Study, University of London) and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, under the Open World Research Initiative (OWRI) of the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

This seminar was the launch event for a project to make the first professional recordings, public concerts, and performing edition of a selection of the songs of Pedro Ximénez Abril y Tirado (PXAT) from the several hundred manuscripts held in the National Library of Bolivia, Sucre. The project falls under a developing strand of the artistic and scholarly work of Guildhall School, focusing on Hispanic music, inaugurated and led by Professor Sir Barry Ife.

L-R: Nigel Foster, Rafael Montero, Jonathan Eato, during the recording session on 19 August 2020, St Matthias Church, Stoke-Newington, London

Pedro Ximénez Abril y Tirado was one of Latin America’s most successful and prolific composers of the early 19th century, whose work spanned the critical period of the establishment of independent Latin American states in the period after the end of the Spanish Empire. Known at the time as “El sinfonista de los andes”, he learned his craft during colonial years, but was able to contribute to the body of early postcolonial repertoire. In the 20th Century his work fell from view. It is only now, with the greater interest in postcolonial studies and the rehabilitation of indigenous musics that his work has begun to receive scholarly and artistic attention. His work exemplifies the cosmopolitanism and cultural mobility that was an important strand in the establishment of a distinct Latin American cultural life. At the peak of his career he occupied a prestigious position as director of music at Sucre Cathedral, the most important cultural and religious city of the newly created state of Bolivia, under the direct patronage of President Andrés de Santa Cruz.

These secular songs exemplify this cosmopolitanism in both words and music. The poems are drawn eclectically from European and Latin American sources (including, unusually for the time, some women poets, such as Caroline-Stéphanie Félicité Du Crest (France 1746 – 1830), and the Ancient Greek poetess Sappho). In his post-colonial period he set to music South American poets like Esteban Echeverría and Manuel Martínez, from Argentina and Mexico respectively, who took their inspiration from the culture in which they were living, working in the neoclassical and romantic poetic style. Echeverría’s writings also inspired the Argentinian constitution after independence from Spain. The music also shows stylistic variety. Whilst the predominant style draws on European models (with similarities to Mozart, Haydn, and Bellini), there are also strong indigenous influences in some, particularly in a set of “Jaravi”, songs drawing on the ancient traditional genre of Andean music and indigenous lyric poetry.

In all of these respects Pedro Ximénez exemplifies the cultural syncretism that has been a prevailing feature of Latin American music at many historical junctures. At a time when the impetus to de-privilege the European classical canon grows ever stronger, Ximénez is a neglected composer of the highest quality whose works deserve wide contemporary exposure and integration into the corpus of established art songs.

The project was conceived and initiated by Rafael Montero, freelance singer and project leader, an Argentinian of native American Bolivian descent. In a conversation between Dr David Irving (ICREA, Barcelona) andJuan Conrado Quinquiví Morón, a musician and researcher based in Sucre, Bolivia, participants heard how Montero established a partnership with Morón, who has taken the primary initiative to start transcribing and editing the 300 or so songs whose original manuscripts (hitherto in private ownership) have recently been acquired by the National Archive of Bolivia. To date some 40 of the songs have been transcribed, and it is from these 40 that a selection is being made for the project. Morón has designated Montero to be the first to record these songs.

PXAT was a prolific composer, and also composed many works other than songs including 40 symphonies, masses, vespers, salves, tonadillas, music for guitar, piano, Christmas carols and songs. Participants learned that there has been a gradual revival of regional interest in PXAT, which has led to a range of publications and performances, and a commercial recording of all extant works for solo piano. Even so, less than 5% of his works have been performed in modern times, and the songs hardly at all.

In a conversation between Professor Barry Ife (Guildhall School of Music & Drama) and Dr José Manuel Izquierdo König (musicologist and author of doctoral dissertation on Tirado) it was noted how unusual PXAT’s career trajectory was, at a time when most musical formation was offered by the Church. PXAT was supported by his family, prominent in the Arequippan elite, and pursued a career focused mainly on secular music until at the height of his reputation he was appointed Chapel Master and Professor of Music at Sucre cathedral, after which point his output concentrated on church music. However, it was during these later Sucre years that these secular songs, many written earlier for guitar (which was PXAT’s great passion), were rewritten for piano, in view of changing attitudes to the guitar in newly postcolonial Latin America.

In conversation with Professor John Sloboda (Guildhall School of Music & Drama) Rafael Montero introduced the three songs recorded specifically for the seminar. Because of Covid-19 restrictions on access to performing and recording spaces, recordings were made with a modern concert grand piano, although the main project will use a fortepiano of the type in common use at the time. Two of the songs (A Maria, and A Dolores) were Cancións, which – as observed by pianist Nigel Foster – have strong elements of the bel canto style of composers such as Bellini (a link confirmed in the discussion pointing to PXAT’s writing out of bel canto ornamentation of the song of an Argentinian contemporary). The third song (Jaravi No, 11 A Donde vas, dueño amado) draws heavily on the indigenous Andean form, which is a lament for the loss of loved ones, and which, in this contemporary performance is dedicated to all those who have died from the Coronavirus in recent times. This performance is now available on youtube at: https://youtu.be/qxpuJR0-nZE .

The seminar concluded with a lively discussion from among the 60 or so participants. There was a notable concentration of Spanish-speaking voices from the South American continent, complementing the European attendees, a positive feature of an on-line event such as this, which compensates for the unusual restrictions under which this event was prepared for and held. Particular thanks are due to Dr David Irving and Rafael Montero, who through their real-time translations ensured that Spanish speakers could better follow the proceedings.

(Details of contributors can be found online here)

Professor John Sloboda, Guildhall School of Music & Drama