Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

The Challenges of Performing Austrian Refugee Theatre 80 Years On: Hugo Königsgarten’s ‘Die Rückkehr’

Clare George introduces the Making Theatre in Exile project:

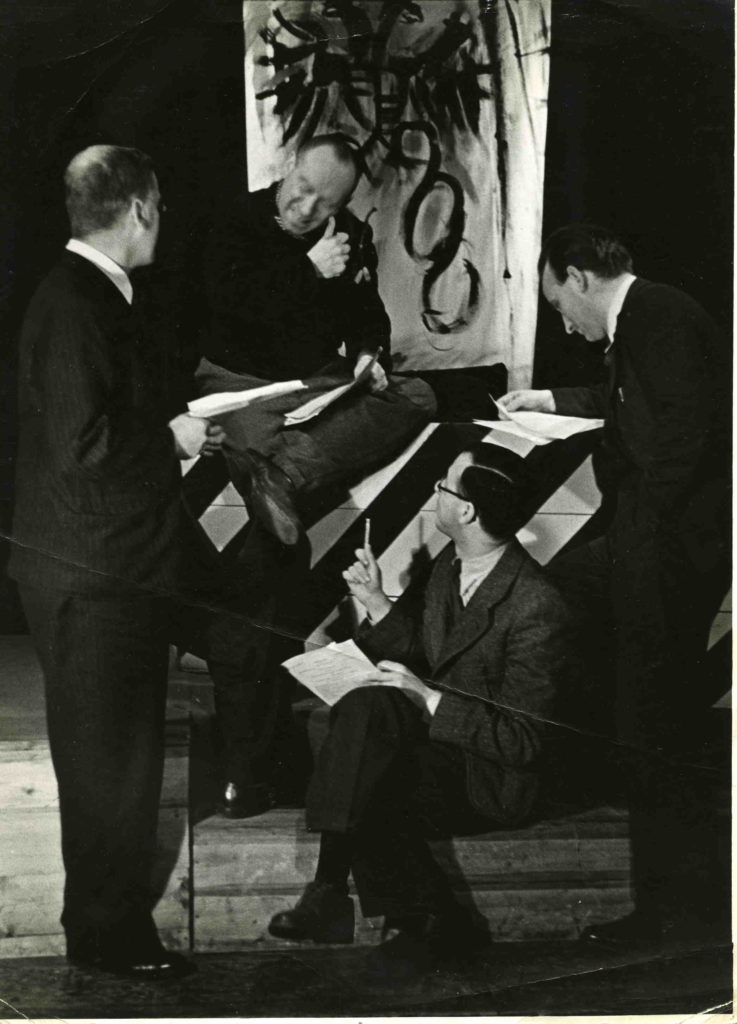

The ‘Making Theatre in Exile’ (MTIE) project, which culminated in a specially produced performance piece for the ‘Being Human’ Festival at the Hampstead Jazz Club on 14 November 2019, grew out of an attempt to revive the scripts in the Miller Archive of the Laterndl, an Austrian exile theatre from the Second World War. Since that time the scripts had been stored away in boxes, consulted and analysed by academic researchers, but unused by actors and unseen by theatre audiences for whom they were written. Would the stories written by and about a group of German-speaking refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe for the Laterndl theatre still have relevance 80 years later, or would the change in performative context be so great that they would have little meaning for today’s audiences?

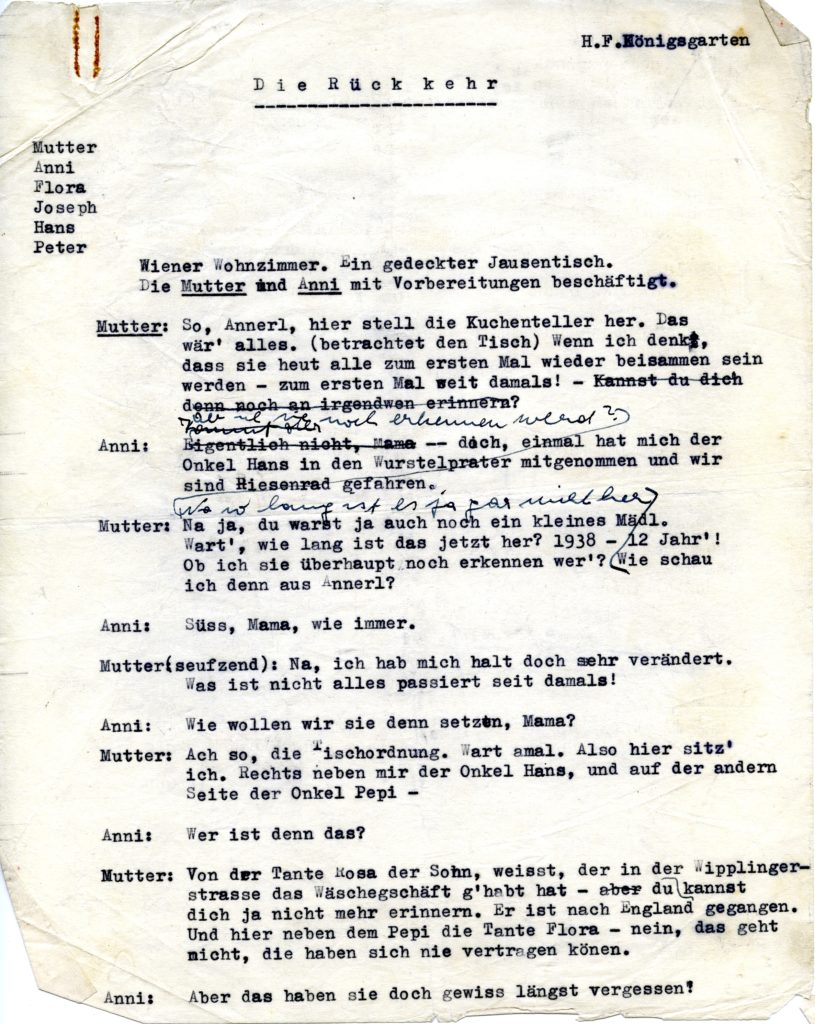

A possible obstacle to the successful engagement of audiences in the UK with the scripts was their translatability. The Laterndl had attempted to appeal to British visitors, marketing its productions in both English and German, but its primary audience was the Austrian refugee community and performances were predominantly in German. In order to increase local community awareness of the theatre the project would need to find a way to make the sketches accessible to non-German speakers. As in the original, a compère would introduce each sketch in English, and English translations of some of the shorter scripts would be provided in the programme. However, some of the longer scripts, like Hugo F. Königsgarten’s comedy ‘Die Rückkehr’ (‘The Return’) for example, presented more of a challenge.

Set in 1950, ‘Die Rückkehr’ sees members of a Jewish family reunited in Vienna for the first time since the end of the war, most of whom have spent the past 13 years scattered across the world in exile and who now plan to settle back in Austria. The sketch anticipates the increasingly transnational identities of those who spent years in exile, and who bring back to Austria the language and customs acquired in the countries where they found refuge. The sketch pokes particular fun at the British through the UK-based refugee Onkel Hans, who plans to establish a café in Vienna to introduce the Austrians to the delights of British cuisine like ‘beans on toast, spaghetti on toast’. Such humour clearly appealed hugely to the local refugee community and may have provided an outlet for the frustration of those who found Britain an alien and often unwelcoming environment.

Because much of its humour is based on the multilingual (in)competence of those who have been in exile, translating the sketch directly into English would have lost much of its meaning. Onkel Hans describes the weather and his journey in a comical mix of German and English littered with ‘false friends’ and mistranslations: for instance, ‘a stormy crossing’ became ‘eine stürmische Kreuzung’.(1) These probably worked with the increasingly bilingual Laterndl audiences, but for non-German speakers amongst the MTIE audience, they would have little meaning. Re-animating scripts like these required bilingual performers like those from the international theatre company Foreign Affairs, specialists in theatre in translation. They followed Königsgarten’s German and English script and retained the original humour, but their performance also added new layers of meaning through the linguistic and performative versatility of the actors. In ‘Die Rückkehr’ the three actors covered seven characters and switched from German to French, British English, American English and Cuban Spanish in rapid succession, making it an entertaining scene even for those with little German.

A work-in-progress performance of ‘Die Rückkehr’ and other Laterndl sketches was staged in April 2019, following which a more ambitious plan was conceived by Foreign Affairs director Trine Garrett and Miller Archivist Clare George. Rather than presenting the sketches as discrete items, the production would weave them together with extracts from letters, reviews and other records in the archive to create a new production about the Laterndl and the archive. In the opening scene the actors would ‘discover’ the Millers’ papers in an old suitcase, a performance device which would then frame the individual scenes, with the actors transitioning between their roles as ‘discoverers’ of the records and the figures whose voices are captured in them. Adding this historical context would make the sketches more meaningful to today’s audiences, and emphasising the discovery of the sources of the stories would provide scope to explore the idea of ‘discovering’ the past through the provisional piecing together of information from fragmented archival traces.

‘Die Rückkehr’ provides an interesting example of how this was achieved. A clash of voices from newspaper reviews retrieved from the suitcase reflected the mixed reviews that the sketch received from the exile community. It was in fact one of several that sparked a fierce debate in 1941 over the role of the exile theatre and whether it should promote political engagement or simply entertain. Whilst one reviewer praised the sketch for its great comic value, another, in the Austrian Centre’s Zeitspiegel, advised sternly that rather than making jokes about the return to Austria, the theatre should show ‘wie es wirklich aussehen wird, damit wir alle besser für ihre Verwirklichung kämpfen können’.

A series of letters from Königsgarten to Miller, one of them referring to a now missing alternative script for ‘Die Rueckkehr’, provided an opportunity to highlight the instability of the ‘realities’ of the past constructed from archival records. In one letter, dated early August 1941, Königsgarten proposes that the Laterndl stage a comedy featuring the exiles back in post-war Vienna; he was sure of its success as ‘eine richtige Lachszene’ and the script was already written. By the time the production opened the following month he was having second thoughts, however, particularly about the ending. A second letter reveals that he now wanted ‘Die Rückkehr’ to deliver a stronger, more serious message about the possibility of continuity between past and present and to show, he implied, that returning exiles could pick up where they left off and that the family could become ‘Austrian’ again. He enclosed a new ending for the sketch, which he asked Miller to use instead; it would, he wrote, introduce a grandfather figure who would represent the possibility of ‘die Rückverwandlung der Familie in eine österreichische’.

It was decided that for the MTIE project the second letter would be ‘discovered’ and retrieved from the suitcase only after the sketch had been performed. Without knowledge of the second ending, the audience would assume the sketch they were watching was a re-performance of the original from 1941. Only after the sketch, with the reading of the second letter, would the information about a new ending be revealed, which would call into question the status of the script in the archive and thus also the (re-?)performance. Such uncertainty underlines the challenges that researchers face when trying to uncover the realities of the past from archives, whose meaning shifts according to contextual information that may or may not have survived.

Königsgarten’s intention of showing the possibility of Jewish exiles returning home and families seamlessly becoming ‘Austrian’ again may appear rather innocent to audiences today, given the events that took place in Austria between the performance in 1941 and its setting in 1950. Königsgarten was presumably hoping to offer some comfort to the community despite any knowledge that he may have had about what was happening in Austria. There is no record of whether Königsgarten’s second script was actually used by Miller, but the MTIE performance attempted to underline the shift in historical perspective since the sketch was first performed by subverting the notion of the grandfather representing continuity. Without him, the actors interject, there is no one to transform the family back into being ‘Austrian’ again. The very absence of this symbolic figure signals the impossibility of the continuity that Königsgarten had optimistically imagined.

The ‘Making Theatre in Exile’ project was an attempt to bring back to life the records of a refugee theatre which helped bring together a community living in fear and uncertainty in London 80 years ago. Those records, so carefully retained and preserved over decades by the Millers, inspired a new multi-layered performance which retold their stories in ways which reflected the shifting meanings of the archival records but also tried to make them meaningful and relevant to today’s audiences.

Dr Clare George, Miller Archivist (Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies)

The Making Theatre in Exile project was generously sponsored by the Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust (University of London) the Austrian Cultural Forum London, the Being Human Festival, and the AHRC-funded Open World Research Initiative (OWRI)

(1) A ‘stormy crossing’ is a ‘stürmische Überfahrt’ in German; a ‘stürmische Kreuzung’ is a ‘stormy crossroads’ in English.

Bringing Archives to Life for the Being Human festival

Clare George introduces the Laterndl, providing the background behind the Making Theatre in Exile project

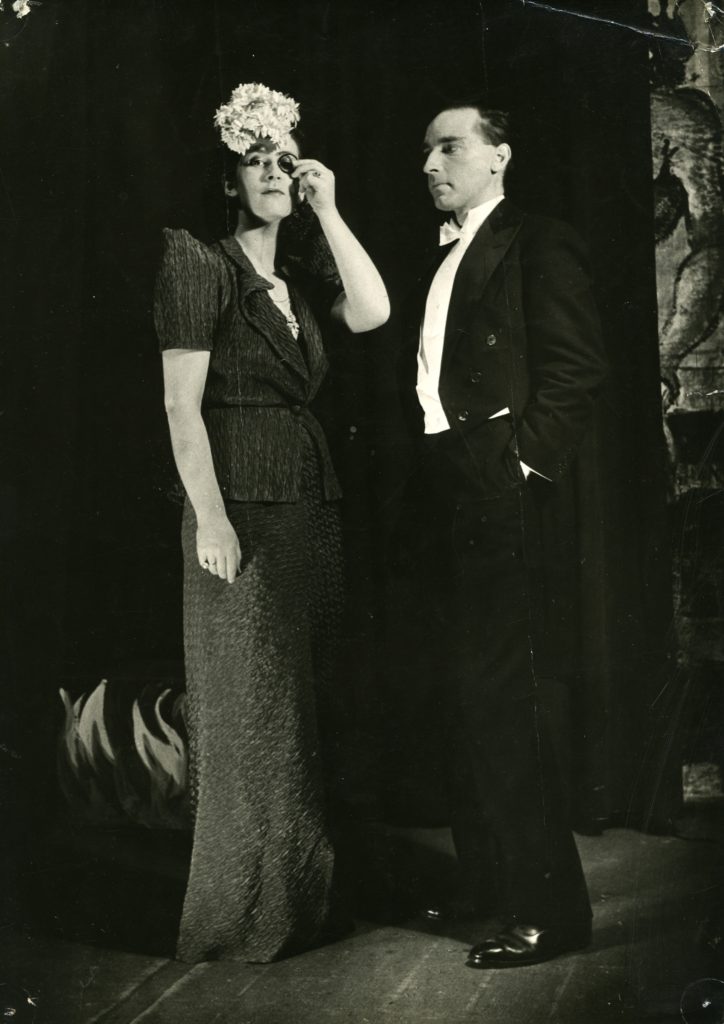

Eighty years after it first opened in Hampstead in November 1939, the story of the Second World War Austrian exile theatre, the Laterndl, was brought to life by the international theatre group Foreign Affairs as part of the 2019 Being Human Festival. The ‘Making Theatre in Exile’ (MTIE) project saw performers delve into the archive of its director Martin Miller and weave together extracts from letters, scripts and newspaper reviews to create a 1930s’ Viennese cabaret-style evening of sketches and songs with accompanying music arranged and performed by pianist Malcolm Miller.

The Laterndl was founded in June 1939 by members of the Communist-inspired refugee support organisation, the Austrian Centre. The idea was to establish a theatre that would ‘keep alive the light of Austrian culture’ at a time when Austria had politically ceased to exist. It was to be modelled on the Kleinkunstbühne or small arts theatres of mid-1930s’ Vienna, where many of the Laterndl actors and writers had produced political cabaret before fleeing Austria. These semi-underground stages had provided one of the few remaining public spaces in which criticism of the regime and the growing influence of Nazi Germany could still be expressed during the Austrofascist period of 1934-1938. Apart from two breaks, enforced by the compulsory closure of all theatres at the start of the war and the internment of many of the actors as enemy aliens in May 1940, the Laterndl performed regularly for the following six years. The theatre provided a platform for an array of new works telling stories from the refugees’ world and attracted nearly 10,000 visitors within the first seven months alone. It raised British awareness of Nazi atrocities, support for the war against Hitler, and brought a beacon of hope to the 30,000-strong traumatised community of Austrian refugees.

Despite these achievements, like many other refugee groups in history, the Laterndl left relatively few archival traces of its activities. Its existence is noted in the state records at The National Archives, but only in the context of the potential dangers posed to the nation by its members gaining UK citizenship after the war. As archives theorist Andrew Prescott notes, the experience of exile generally appears in the official archives as ‘an anomaly, with fleeting and transitory individuals and groups seeking help or posing problems’, so to find the refugees’ own stories we must look outside the scope of public records. Sadly, no central records store was recovered when the Laterndl ceased its activities in 1945, so we are reliant on those records which survived the selection and omission processes of individual actors. This is a subjective and arbitrary matter even for fixed groups in settled times, but still more so for those living with the hardships and uncertainty of refugee life in wartime London, for whom record-keeping would hardly have been a priority.

Given this context, the fact that two of the theatre’s main figures managed to salvage and preserve a significant number of records of the Laterndl’s activities over many decades is a cause for some celebration. Hannah Norbert-Miller (then Hanne Norbert) and Martin Miller, who was to become her husband, were key figures and involved in many different aspects of the theatre’s productions for the first three years of the Laterndl’s existence at least. In addition to Miller’s directing, both were lead actors, and Norbert-Miller also played the role of English-language compère. Their records, whilst not covering all the productions, nevertheless represent probably the most complete archive of the theatre in existence and offer an unparalleled insight into the refugee actors’ world. Researchers in the IMLR’s Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies have used the Laterndl programmes to show how, as in Vienna, each production consisted of short dramatic sketches and songs, often of a topical and satirical nature. The fragments of English-language compère scripts reveal how the actors appealed to non-German speaking supporters like Sybil Thorndyke, H.G. Wells and J.B. Priestley. Letters from writers and other figures close to the theatre point to the deliberations and heated political discussions which must have taken place amongst the artistic team but which often went unrecorded. Newspaper clippings from both the British and exile press show the enthusiasm with which both German and English reviewers greeted the opening of the Laterndl, as well as the differing views on its role as the war progressed.

The MTIE project aimed to showcase the value of the Millers’ archive for opening a window into this little-known aspect of Second World War history. The performance incorporated letters, memoirs and compère scripts to evoke the moving Laterndl performances which kept alive the work of Jura Soyfer, a cabaret writer whose scripts were smuggled out of Austria by his girlfriend, Helli Ultmann, after his death in Buchenwald Concentration Camp in January 1939. Another bundle of letters revealed how Martin Miller’s Hitler speech parody, first performed at the Laterndl, achieved international acclaim after its broadcast by the BBC German Service on 1 April 1939. It would be the first of many satires by German-speaking writers used by the Corporation as part of its anti-Nazi propaganda campaign. Selected sketches by the theatre’s in-house writers were woven into the performance, some performed for the first time since the 1940s, including a song based on the sole surviving record of the Laterndl’s very own ‘Schwejk’ production composed by the theatre’s musical director, Georg Knepler, and harmonised for this production by pianist Malcolm Miller.

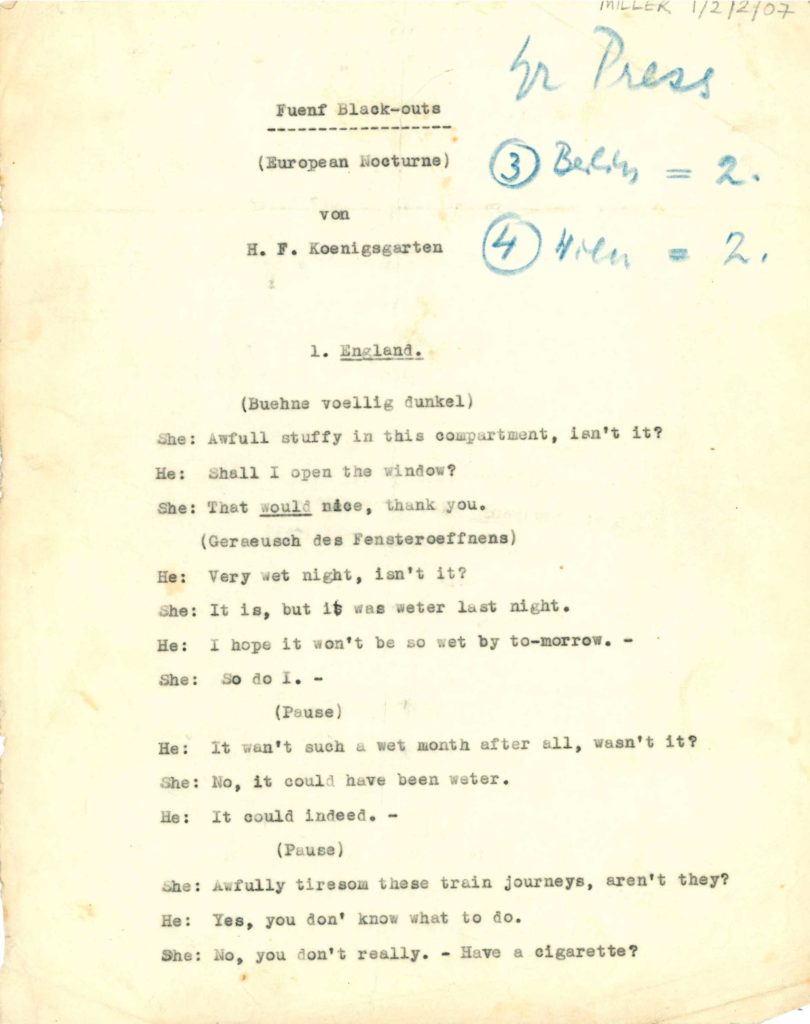

For all the stories of the Laterndl captured in the archive, many more were not – either because the records were lost along the way, or because they were never captured in the first place. Whilst spotlighting those traces of the refugee actors that have survived, the project also aimed to acknowledge the gaps in our knowledge: the issues, problems and questions that they faced and which we will never know about as they are unrecorded. MTIE opened with the discovery of a battered old suitcase containing a jumble of fragile, yellowing papers, some just scraps, to which the actors repeatedly returned – sometimes finding new and illuminating stories, but sometimes searching in vain for a particular record. One such sketch, ‘Five Black-outs’, ended abruptly at the third Blackout scene because the rest of the script was missing; rather than covering up the gaps with a new and fictionalised ending, the performers jolted to a stop. In this way, the performance aimed to expose the notion that the records present us with a complete and knowable account of the refugee theatre’s history as an illusion.

Acknowledging the gaps in the archive and our knowledge of the past of course enhances rather than diminishes the value of the archival material which has survived. As the MTIE project hoped to highlight, those rare glimpses into a little-known past afforded to us by the Millers’ records give us great reason to be thankful for their survival.

Dr Clare George, Miller Archivist (Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies)

The Making Theatre in Exile project was generously sponsored by the Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust (University of London) the Austrian Cultural Forum London, the Being Human Festival, and the AHRC-funded Open World Research Initiative (OWRI)

From Refugee to UK Citizen

Jana Buresova talks about women refugees from former Czechoslovakia to the UK, from 1938 onwards

The ‘refugee question’ remains perpetually topical. Government policies wax and wane, public sympathy ebbs away or gives way to prejudice, and the refugees in question generally remain anonymous, no longer ‘stories’. Yet behind the headlines and the broad sweep of history are the personal challenges, successes and failures worthy of consideration, and the contributions to the host country that merit recognition — as in the case of women from the former Czechoslovakia who found refuge in Britain between 1938 and 1950 (and onwards).

These women risked their lives to escape. Yet how does one reconcile the difficulties experienced in a foreign country, with the benefit of safety from an oppressive authoritarian regime, be it fascism or communism? If the past is truly ‘another country’, should one leave it behind, or recreate it in a new one? Is there indeed a choice, and if so, how is this realized in an alien environment? These dilemmas resonate into the twenty-first century.

It is exactly such issues that my book addresses. Although it focuses on women, it certainly does not exclude men, nor is it a composite review of gender theories. Rather, it complements works concerning the Czechoslovak armed forces that served in Britain during the Second World War and aims to fill a gap about the lives of women refugees hitherto neglected in British-Czechoslovak socio-political historiography.

That gap was apparent from both perspectives. Young people growing up during the communist era had little or no notion of the lives of their compatriots in Britain, regarded as traitors by the regime. Meanwhile, many second generation children in the Diaspora have, as mature adults, only belatedly sought information about their parents’ backgrounds. The gap was therefore treated in two ways: by archival research and, despite the potential pitfalls of oral history, by giving the women a ‘voice’ and recording it for posterity.

My book traces the chronology of these refugee women from Czechoslovakia to Britain: their reasons for leaving, arrival and adjustment, internment, experience of cultural institutions, wartime service, contributions to society and, ultimately, the problems of repatriation/remigration. It also highlights certain challenges faced by women alone: the ‘gender role swap’, whereby women had to take on the head of family role from the men, and their role as mothers, raising children with a sense of Czechoslovak identity away from the homeland.

Many of these women came to feel liberated in exile. Owing to straitened circumstances, some women developed useful practical skills, while others found that their independence allowed them to pursue careers not previously imagined to be within their scope. What emerges is a sense of humour, a will to ‘get on and make the best of things against all odds’ and a determination to ‘do their best for their children, to give them a better chance in life’. The majority of women interviewed had created a future built on the past.

I have been asked why I never included anything of my own family background, but it was important to stand back from the topic I wished to present in a balanced, not a personal or emotive manner. Nevertheless, it is there, embedded in the various accounts of other people!

Interviewing them was a privileged insight into their private lives and thoughts.

Jana Barbora Buresova is the author of “The Dynamics of Forced Female Migration From Czechoslovakia to Britain, 1938–1950“. Following its publication in 2019, she was awarded the Honorary Silver Medal of Jan Masaryk ‘For outstanding contributions to the development of relations’ between the Czech Republic and Britain.

She is currently a committee member of the Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies at the University of London, where she completed all her degrees, is co-authoring a book about the Czech Refugee Trust Fund in Britain, and interviewing Second World War refugees/camp survivors for an oral history archive project.

Five Days ‘Exploring Theatre Translation’ in Buenos Aires

Jack Tarlton (actor, director and teacher) talks about the recent workshops held in Argentina, ‘Exploring Theatre Translation‘:

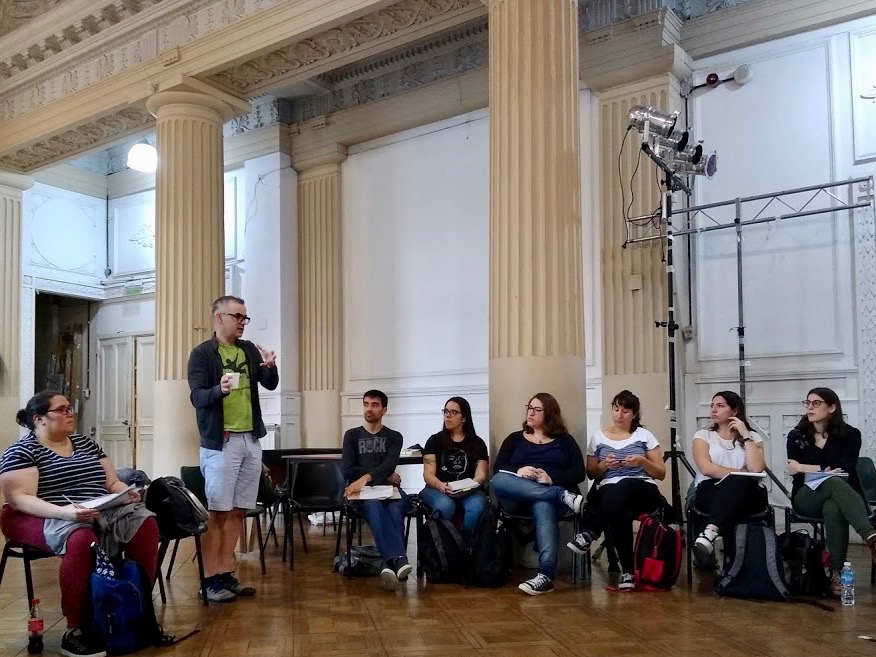

Monday 4th November 2019: A taxi ride through the rain-pelted streets of Buenos Aires. Beside me is Catherine Boyle, Professor of Latin American Cultural Studies at King’s College London and Primary Investigator of the Language Acts and Worldmaking Project. In the front getting the full experience of the wayward traffic is John Donnelly, playwright and screenwriter. The three of us have never worked together before but today, along with Lucila Cordone and María Laura Ramos of the Argentine Association of Translators and Interpreters, we start Exploring Theatre Translation, five days of workshops with a group of student translators. Using three of John’s plays we aim to offer practical guidance on how to approach the often mercurial process of theatre translating, culminating in the group translating a section of his latest play, The Porter, to be performed in a staged reading on Friday night.

We’re working in Paco Urondo, an arts space that is part of the University of Buenos Aires, which John perfectly describes as “raffishly beautiful” and is the former dining room of what was the city’s first luxury hotel. The room is cavernous and the sound of tango music dancing through a PA system echoes around the space and welcomes us in. We meet Lucila, María Laura and the students and arrange our chairs in a wide circle. Although each of us brings a wealth of practical expertise and we have a well worked out plan for the week we are keen to keep a sense of discovery and improvisation alive, so this does feel like an experiment. And the bulk of the workshop will be carried out in English and we have yet to assess the level of fluency amongst the students. I briefly introduce the team, give a very quick overview of what we hope to achieve and then hand over to John for “The Match Game.”

John starts, striking a match and then attempting to give his life story while it remains lit – “When I was young my friend’s father would take us to football matches where I learnt a lot about storytelling and about how men relate to each other” – before handing the box of matches around the circle. “I am a student of Lucila’s” – “I live outside of Buenos Aires” – “I am scared of fire but actually this isn’t too bad.” – “If I cannot become an actress then I will die.” Instantly, you get a sense of everyone in the room, while watching how they try to keep the flame alight or blow it out is as illuminating as what is actually said. What I hear most is “I am very excited to be here” and although I think initially this is perhaps just filler, I quickly realise that there is a true sense of excitement and anticipation in the room towards the project. It’s good to learn too that people are coming to the workshop from widely different backgrounds; some have experience of working on the stage while others have never translated drama before. And to discover that their proficiency in English seems very high.

We start by looking at the first few pages of The Knowledge, a play of John’s that was first performed at the Bush Theatre in 2011. We deliberately have not given it to the group beforehand so the first read is a collective rush, as we each take it in turn to read one line of dialogue going round in the circle, and meet a group of unruly secondary school pupils trying to undermine their new teacher. Challenges are thrown up straight away. How would you translate the very first line – “Top Shop?” What action has preceded the start of the play? What is the equivalent in Spanish of an English character using the Spanish word “Nada”? The group is divided into pairs to locate these challenges and to attempt a very rough first draft of the scene in Argentine Spanish.

When it’s time to report back we quickly realise that most became mired in the first page or so. The specific references to the South East of England have prompted lots of conversations about where to locate the play. With Catherine encouraging them to set aside these worries for now we then give them a longer passage to work on which results in a far greater fluidity and the translated passages are shared by the end of the afternoon. Students in groups of five gamely hunker around a laptop to read and bring the scene to life. We finish by asking the students how they would translate the title The Knowledge, with its multitude of meanings into Spanish.

By now the rain has abated leaving a bright but still muggy afternoon, through which we walk to Lenguas Vivas, where Lucila and María Laura teach, for a reading of part of John’s version of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull and a Q&A. I auditioned for the original production by Headlong in 2013 so I am extremely happy to finally play Konstantin to John’s Petr, with the other parts read by Catherine and two of the students. In the Q&A that follows John speaks of his belief that Chekhov’s original does not exist as it once did; that the passage of time and its elevation to classic status has blunted the force that it once had, of his desire to make the audience experience it anew from the famous first line onwards, and how he took the play apart and tried reordering scenes only to reassemble it in Chekhov’s design. There is an open, relaxed feeling to the event. Students whisper our questions and answers to their tutor in Spanish to be assessed and others who are walking by are drawn into the room to join us. Behind us the last of the rain clouds are burnished orange and deep grey as the sun begins to set on our first day.

Tuesday 5th November: Bright sunshine this morning and which will last all week. After Catherine leads us through a series of bilingual tongue twisters we settle down with The Pass, which explores a footballer struggling to deal with fame and his sexuality. First performed at the Royal Court in 2014, it was released as a feature film in 2016.

We gave the play to the students last week so that they were fully aware of the whole story. Over the course of the play’s three acts it is revealed that what one character is doing to another is very different to what it originally appeared to be and we felt it was fundamental for the translators to grasp this. We read a section of the first scene and then ask for comments. In an attempt to not get caught up in an over-complicated discussion we encourage each student to simply start with “I noticed that …” or ask us a simple question such as “What is … Portsmouth?” This provides short, insightful points upon which to start a dialogue and we adopt it as a working model for the rest of the week, locating and unpicking the specific challenges for each script.

With a far greater understanding gleaned of the first scene I then turn their attention to a later scene to encourage them to attune their thinking to how an actor would approach the play. Together we work out the objective of each character; what they want from the other, the obstacle that is stopping them from achieving this and the actions that they perform to get around it. As a writer John will do this with his own text and I feel it is important for the translators to find that perspective also, to dig into the play and not to look down on it purely objectively. I set them the task of writing an action for each line to show what the character is doing to the other with it, but having thought that I had explained the concept clearly when they present their work almost all of them misunderstood the brief. This proves an extremely important lesson for us. We have to remember that this work is tricky and we are trying to teach it in a language that is not the students’ original and so to strive always for clarity. Upon giving my own thoughts on what the actions are however they all seize the concept and we finish the afternoon with everyone successfully translating these two sections of the play and performing them for the rest of the group. There is a real feeling of achievement from all as they share their completed work. Another quick-fire round of how they would translate the title of the play and we are done before all head to the theatre for the evening.

Wednesday 6th November: This morning it is my turn to lead the morning game and soon everyone is miming, shouting and running back and forth with “Lemonade”, a game that I was introduced to at youth theatre and have never tired of sharing. Properly warmed-up we then turn our attention to The Porter.

It is a taut, unsettling play about class, sex, shifting loyalties and how much we can believe the past. It is a play with sweaty palms. The students were sent it some weeks ago and respond brilliantly to it on our first read together, discovering that the first dramatic arc concludes at approximately thirty-five minutes in. This will be what we present on Friday evening then, which will be very first time the play has been performed in public. John divides this into seven sections and the group into pairs to work on a section each. We have learnt that two people work best together, enabling each translator to use the other as a sounding board and their combined energy to drive them forwards. After some time with their pieces we come together for questions and “I Noticed That…” which prompts the drawing of a detailed league table of British supermarket chains, music festivals and types of tea. It starts to come into focus that this play is set in “this imagined England” of John’s, a landscape created though his own perception of nationhood and class and now to be engendered anew through an Argentine perspective.

Each pair is then given the rest of the morning and into the afternoon to produce a rough first draft. Each have their own specific challenges, from dealing with seemingly out of character vocabulary, to the sexual subtext of everyday interactions, to translating a passage of 17th Century metaphysical poetry. Our guiding note to them all is to think about what the characters are doing to the others with each line, that “the force of the utterance” – as David Bellos puts it in his book Is That a Fish in Your Ear? – is far more important than the literal sense. Above all, John encourages them to be bold, to take ownership of the text, it is becoming theirs now.

In the mid-afternoon we gather to read it. And already there exists a new play. A bit rough and with the joins showing, but it has a momentum and a playfulness that speaks to us all, even to John and I with our limited grasp of Spanish. It is hugely inspiring to see how after only three days this group who are still getting to know each other have created something so strong and supple and which will be given to the directors and actors to start work on tomorrow morning.

Thursday 7th November: John has already spoken about the process of writing and staging a play as being one of release. As a playwright you write a play, which is then given to the director, who gives it the actors, who finally give it to the audience. Here though, the play was given to the translators first and this morning it is their turn to release it to Nicholas Lisoni, the director of Paco Urondo who will lead the actors Annalia Malvido, Horacio Vera and Ezequiel Lozano in an initial table-read before handing it over in turn to his long-time collaborator Andrés Binetti who will direct the staged reading tomorrow night. This is the first time that the translators will discover how actors coming to it purely as a piece of dramatic text without being part of its creation will respond. We feel it is important for the translators to sit in on the all sections being read, to learn the discipline needed to be a translator in the rehearsal room, and so after Nicholas leads us all in our morning warm-up, everyone gathers for the first read-through.

As the actors work through the play I feel the thrill of a different kind of release. I would normally worry if the more I worked on something the less I understood it, but here I find it exciting that something that had been so familiar to me just yesterday now already exists in Argentine Spanish, with its own shape and inner structure, the details of which I will never fully grasp. There are still surprising moments of recognition though when a line lands in Spanish and I instinctively know what it was in English. What a fantastic way to start to learn a new language.

After the reading the actors have many questions for the students, most of which are about punctuation and the uncharacteristic vocabulary that they felt was inconsistent. This turns into a passionate debate with everyone involved before Catherine has to remind the group only to comment on their own section.

Everyone is buoyed by the first read-through, especially when Nicholas half-jokingly asks if the rights are available. An early lunch and then the students have the bulk of the afternoon to rework their sections based on the feedback they have received. Warned against too much tinkering by Catherine who reassures them that the work is already very strong, most of the reworking involves finding greater clarity. We reconvene and the play is read once more by three of the group and then a final opportunity to redraft before tomorrow morning.

This evening tickets have been arranged for us all to see Minefield, an extraordinary play directed by Lola Arias and performed by eight veterans of the Falkland / Malvinas Islands conflict. Thrilling, moving, funny, angry and compassionate it is one of the finest pieces of theatre I have seen for a very long time and I am so glad that I can experience it as part of a predominantly Argentine audience.

Friday 8th November: A staged reading can mean many things. Often it involves actors simply reading from their chairs but Andrés Binetti shows the same dynamism in approaching the play as he does in the highly physical warm-up game that he starts the day with and that definitely needs no translation. Although they still have their scripts in their hands the actors fully embrace the text, combining a beautiful naturalism with a heightened, abstracted staging. An impromptu performance space is erected using six chairs, stage directions and sound effects are spoken and scraped through a microphone, the characters intimidate one another by hovering over each other, or seduce each other by sitting a certain way in a chair. Simple lines are mined for nuance, while a longer passage that originally elicited laughter from the group is played with a solemnity that while possibly was not what was intended is fascinating to see transformed in that way. I can only imagine how empowering it must be for the students to see their work being treated with the same robust respect that any professional script would be. Also, the physicalisation reveals real differences in British and Argentine behaviour. While every morning here starts with a kiss Hello, does the moment when a husband makes a show of kissing his wife on the cheek carry the same weight?

Working through what we would normally call lunch, time is called on the rehearsals in mid afternoon so that the actors can rest before the evening show. We spend the remaining time sharing our observations of the rehearsal process, using our now familiar prompt of “I Noticed That …” Catherine then shares her experience of being a translator in numerous rehearsals, encouraging all the students to stand up for their work and to find their own agency within the company.

We then break for the chance of some late afternoon sun for those who want it, while I arrange the chairs for the audience as the lighting is rigged for tonight’s performance.

When it comes it is magical. Ezequiel, Horacio and Annalia perform with vitality and real emotional investment. The process of release is completed as the audience takes this play as their own, staged by the actors and director in a day, and translated in two days by a group who only came together at the beginning of the week.

Afterwards a photograph is taken of us all and I am suddenly made aware of how many people were involved in creating the piece tonight and that although it was the culmination of the week, it was probably not the most important part. I believe that what was more important was the process itself. Three people from Britain and two from Argentina discovering how best to impart their knowledge and to draw the best out of each other and how we in turn could learn from the students. It was they who provided the real engine of the work. They responded brilliantly to our proposals and deadlines, producing multiple scenes from The Knowledge and The Pass, learning from John’s own experience of adapting The Seagull and then melding their separate scenes into one cohesive whole for The Porter. Over five days there truly was an exchange of ideas as we discovered how best to translate the human experience from one culture to another.

Our time together exceeded all my expectations. So now, the work begins to bring an Argentine playwright and actor to a group of students in Britain. I can’t wait to get started.

Jack Tarlton is an actor, director and teacher. His stage work includes lead roles at the National Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company, Young Vic, Royal Exchange Manchester, Sheffield Crucible and in the West End. His screen work includes “8 Days: To the Moon and Back”, “The Imitation Game” and “Doctor Who”. He has directed numerous staged readings of international work and has taught Shakespeare and modern drama studies and adaptation of prose for the stage at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, Oxford University, East 15 Acting School and for The Old Vic and Out of Joint and was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Modern Languages Research at the University of London.

Generously supported by the AHRC, OWRI Cross-Language Dynamics, and Language Acts and Worldmaking, AATI, and Instituto de Artes del Espectáculo and Centro Cultural Paco Urondo (Universidad de Buenos Aires)

Where are all the women?

Barbara Spicer reports on the ‘Translating women’ conference held at the IMLR on 31 October – 1 November 2019

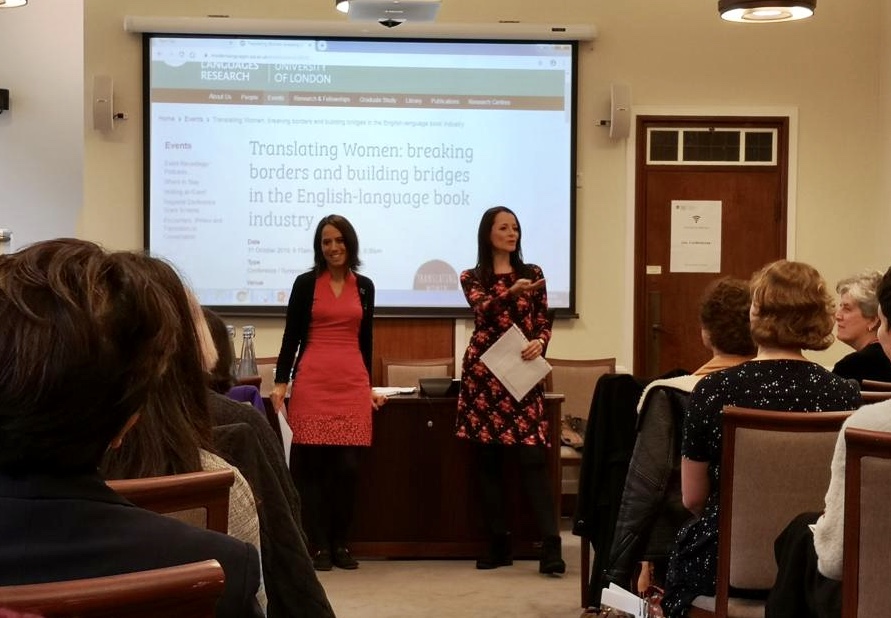

Translating Women 2019 was more than just a conference. Literary translator Tina Kover, speaking at the two-day event at the IMLR, captured the warmth, conversations and hospitality beautifully: it felt like a ‘family reunion’. Indeed, the event reunited people who already knew each other virtually; translators, activists, authors, academics, publishers, students at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. The aim of the organisers, Helen Vassallo (University of Exeter) and Olga Castro (University of Warwick) was to promote synergies between academic and publishing contexts. My own reasons for attending were both personal, as a reader and feminist, and academic, as a postgraduate research student investigating the translation process through a feminist lens.

In her inspiring keynote on the first day, Margaret Carson (City University New York) outlined key events in the timeline of the Women in Translation (WIT) movement, including her co-creation with Alta L. Price of the WIT Tumblr in 2015. Although there are still more men being translated, published and reviewed, according to Carson ‘the gender gap and other exclusions in translation are now part of the conversation’. In a digital age, this conversation is increasingly happening online. (Carson’s ‘Notes from the “Translating Women” conference’ are available on the WIT Tumblr.) One of the awareness-raising initiatives highlighted in the keynote was Meytal Radzinski’s Bibliobio blog and Twitter presence. Radzinski, who self-defined as ‘just a reader’ during a plenary session on the second day of conference, inaugurated the WIT month in August 2014 having realised the gender imbalance in her own reading.

In the panel session that followed on the visibility of women in translation, freelance literary translator Rosalind Harvey stated that it is necessary to look critically not only at who is being translated but how they are being marketed. This point was taken up by Aysun Kiran who examined the ways Turkish female-authored books are being presented in English translation through their paratexts. Kiran gave an example of a reductive review which features on the cover of Ece Temelkuran’s Women Who Blow on Knots: ‘A beach-read with brains and bounce’. It is hard to imagine the same type of description being applied to a book by a man. The gendered notion of the ‘Great Writer’ in literary translation may linger on, but as Carson asserted, ‘it’s becoming harder and harder to defend in light of #WIT activism’.

In the panel on translation as activism, Chicago-based writer and translator Aviya Kushner introduced the concept of ‘expectation bias’, or what society expects from women writers. Kushner noted the inherent bias in telling any woman what she should write about, and how this affects how and where translations are published and received. This bias, she argued passionately, erases their individuality and narrows ‘the full complexity of women’s lives’ to their domestic sphere. I was particularly moved by Kushner’s readings of two female poets she had translated. One, 92 year old Riwa Soffer, does not conform to societal expectations in her writing. Her poetry deals with lust, sex and ageing. And why not? A wealth of literature is still not getting into readers’ hands, and the editors-as-gatekeepers have, as independent scholar Oisin Harris stated in the session on networks of translation, their own personal histories and gendered readings.

On the conference’s second day, speakers discussed WIT initiatives, networks, ideologies, and the geopolitics of translation. Another reader-driven initiative, Project Plume, was launched by Salwa Benaissa in 2019. An independent literary review, its aim is to champion women from underrepresented languages in English translation. A comprehensive and chronological recap of the conference is available on the Project Plume blog. Corine Tachtiris (University of Massachusetts Amherst) discussed the importance of intersectionality in the discussion on geopolitics, highlighting the ways in which other biases intersect with gender bias to amplify marginalisation. In a thought-provoking presentation, Tachtiris urged the audience to seek to understand the existing structures that exclude, and to self-reflect on the ways we participate in these structures and benefit from them. Her call for more diversity in the translation profession and allyship in creating routes into the industry echoed Chantal Wright’s earlier presentation.

Wright, co-ordinator of the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation, speaking in the session on WIT-promoting initiatives, made a very salient point: modern languages and literary translation are not exclusively for the middle class, and working-class linguists and translators can find another identity for themselves in their other language(s). This reminded me of Kiran’s discussion of Temelkuran who, for political reasons, was not free to write in Turkish and so ‘took shelter in English’. In addition to the lively Q&A sessions and frequent live tweets (under the designated conference hashtag #TWconf19), there were opportunities to connect, to discuss, and to reflect in the breaks and at the evening drinks receptions.

The evening events on both days, featuring authors and translators in conversation, offered fascinating insights into the translation process and different translatorial practices. Tina Kover, for example, began her translation of Négar Djavadi’s Disoriental (Europa Editions) on first reading, encountering the text in the same way as the reader. For Kover, the process is a very private one and so there were no discussions with her author during this phase. In contrast, there was more dialogue between Ariana Harwicz (Die, My Love and Feebleminded, Charco Press) and her translators, who include Annie McDermott and Carolina Orloff, during the translation process. The bilingual readings were a personal highlight of the conference. Powerful and emotional to hear in the source languages, French and Argentinian Spanish, I was in awe of the translators’ renderings into English. Recordings of both evening author-translator events will be available.

Translating Women 2019 was an essential milestone in the ongoing movement for a more equitable, inclusive and diverse world of translation. The conference may be over, but the conversation continues. In a post-conference Twitter thread, Meytal Radzinski expressed a desire to see ‘more voices from around the world taking part’ and a move away from the ‘Anglophone and Euro-Anglophone perspective’. For Rosalind Harvey, it is important that more men are included in future discussions too. There is still work to be done but, in the heartfelt words of Helen Vassallo, curator of the Translating Women blog and Twitter account, ‘We’re not all working alone. We share the same beliefs’. I left London feeling proud to be part of a community that is living, and breathing, languages.

The ‘Translating Women’ conference was organised as part of the AHRC-funded OWRI project ‘Cross-Language Dynamics: Re-shaping Community’ (translingual strand), in conjunction with the Centre for the Study of Contemporary Women’s Writing (CCWW) at the IMLR, and with support from the Cassal Endowment Fund.

Barbara Spicer | Postgraduate Research Student

Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies

The Open University