Living Languages

The blog for the Institute of Modern Languages Research

Archaeology of the Italian Gothic: Sepulchral Literature in Italy in the Late Eighteenth Century

Simona Di Martino (University of Warwick): I am a PhD candidate in Italian Studies at the University of Warwick, funded by the School of Modern Languages and Cultures. I am working on late eighteenth-century sepulchral literature in Italy, advocating the existence of an autochthonous Gothic strain whose origins I am currently investigating.

In 1846, Edgar Allan Poe wrote that “The death of a beautiful woman – is – unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world”, a clear signal that the taste for the macabre, which originated in the Baroque, was still appreciated even centuries later. The Gothic fashion in Europe had already flourished in the eighteenth century, intermingling itself with Romanticism and leaving behind the legacy of the Baroque. According to most critics, the Gothic and its gory themes have never really arrived in Italy. The marginal and short-lasting period called Scapigliatura, which is the most comparable kind of literature to the Gothic novel, appeared quite late in the nineteenth century and has been studied in relation to the ‘fantastic’. However, the whole eighteenth century in Italy is rich in deathly and macabre motifs, both in literature and the visual arts, motifs which cannot be considered entirely an import from foreign models (the British in primis) as generally maintained by scholars.

The depiction of death, and particularly that of a beautiful woman, had already doubtless been the most poetical topic in Italian sepulchral literature of late eighteenth century. Studying this strain, so far neglected by critics, is a very fascinating project to pursue in my opinion, for it allows me to conduct different research focusing on various cultural branches and resulting in composite interdisciplinary work. Furthermore, this kind of investigation would cast a new light on thematical threads across centuries so as to mark a visible continuity between the macabre fashion of the Baroque and Romanticism and reaching to the Italian making of the nation.

I apply the classical canon of beauty, according to which female beauty was traditionally perceived by poets, to the women’s corpses constellating late eighteenth-century works. I follow the short and the long canon described by Giovanni Pozzi (respectively focusing on the face or on the whole body) as well as Massimo Peri’s theory of ‘tetracromatism’ and Elisabeth Bronfen’s theories of the external gaze on dead bodies. My aim is to approach the primary sources by reversing the classical topos of beauty and highlighting the taste of macabre which crosses the centuries. Together with aesthetic reflections on the human body, my study involves the examination of ekphrasis (written description of works of art) emphasising both classical models and medieval themes, such as the visual Dance macabre and the poetical Triumphus mortis. It is important to note that also the Christian world represents a common ground for reflections on the body, portrayals of death and the world of ‘visions’ – particularly relevant in sepulchral literature. Therefore, considering Christian implications is crucial in order to shape a realistic cultural background of that time. Specifically, Philippe Ariès’ Western Attitudes Toward Death from the Middle Ages to the Present constitutes a fundamental work on the changing of funereal practices and grief habits, which finds confirmation in my literary sources.

General overview

My project investigates the rise and the evolution of the sepulchral theme in Italian literature from the late eighteenth century to the first ten years of the nineteenth century, tracing meaningful topoi as core parts of pre-gothic motifs. My study begins with the analysis of Alfonso Varano’s Visioni sacre e morali, completed in 1766 and posthumously published in 1789, and focuses on its reception by successive authors. I employ a thematic, lexicographic, and reception-oriented approach with the aim of tracing the circulation of specific motifs across a determined time-span, bringing together relatively neglected authors of the pre-revolutionary era (not only Alfonso Varano but also Salomone Fiorentino, Aurelio de’ Giorgi Bertola and Ippolito Pindemonte) and canonised protagonists of Italy’s later literary history, such as Ugo Foscolo and, partly, Giacomo Leopardi and Alessandro Manzoni.

My final aim is to reconstruct a sepulchral literary strain at the dawn of Italy’s literary modernity, which supplies later nineteenth-century popular literature with a set of motifs that contribute to the creation of a ‘Gothic’ atmosphere, beyond any strict division into compartments of genre. As Fred Botting argues, the ‘Gothic’ is not strictly a genre, but rather a mode underlying different literary experiences of the modern and contemporary age (from the 1760s onwards), which can be recognised by a combination of coexisting elements: excess, transgression, and self-awareness of their own textual component.[1] For this reason, my project represents a contribution towards an ‘archaeology’ of the Italian Gothic, meaning by this term a historical and thematic reconstruction of the ways Italian culture incorporates and/or autonomously re-elaborates the ‘writing of excess’ informing Western literature at the turn of the nineteenth century. I employ an ‘archaeological’ perspective in order to trace the ‘prehistory’ of the Italian Gothic as it would later emerge in nineteenth-century popular literature. Following Foucault’s statement in Archéologie du savoir, to adopt an archaeological approach means describing discourses in their emergence and transformation, regardless of later canonizations and cultural hierarchies.

Traditionally perceived as marginal within the geographies of European Gothic literature, the Italian domain offers instead, and particularly within the auroral moment I cover, a remarkably fertile field. Sepulchral literature in particular is a very promising field of study. In the past, scholarship has primarily focused on the influence of British ‘graveyard poetry’ on Italian literature, thereby underestimating the largely autochthonous roots of Italian sepulchral poetry of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – including Dante, moral Christian poetry of the Baroque, and the Classical eulogy. At the same time, focusing on foreign models’ reception scholars had not considered the specificity of the ways Italian literature, from a Catholic and Classicist standpoint, deals with the ‘abjection’ of death. Investigating the ‘Gothic’ also enables me to detach my approach from distinctions that have informed criticism on the subject for a long time: eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, pre- and post-revolutionary, pre-Romantic and Romantic, ‘Italian’ and ‘foreign’, realism and the fantastic, literature and para-literature, and ‘high-brow’ and ‘low-brow’ culture. My work, therefore, inserts itself in the recent critical vogue reinstating the ‘Gothic’ as a powerful notion for re-interpreting specific phenomena of Italy’s modern and contemporary literary history: the historical novel in the mode of Walter Scott, mid-nineteenth-century narratives employing gory themes in order to focus on social issues, paranormal-related fiction in magazines at the end of the century, and the occult revival in the 1960s.[2]

Areas of investigations

In terms of theory and methodology, as stated above, I will adopt a threefold approach: thematic (A), lexicographical (B), and reception-oriented (C). This perspective will allow me to investigate phenomena of thematical continuity, from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth century and afterwards, through verifiable data such as semantic fields and word-clouds, as well as publication data testifying to the circulation of a corpus of texts (both poetry and prose). The joint analysis of prose and poetry is indeed one of the characterising features of my approach, in that it enables me to focus on how themes and motifs spread across different genres and writing practices, reinforcing the aforementioned argument about the Gothic being more of a ‘mode’ crossing different forms of writing than a fixed genre.

(A) My thematic approach allows me to trace the evolution of sepulchral themes on the base of specific and recurrent topoi which will become largely popular in later literature, such as: macabre depiction of corpses and ekphrastic representations of death and tombs. An interesting debated topic to this end, which emerges from my study, is the portrayal of Death in terms of gender, which contrasts the male representation of the Biblical Angle of Death and the female Donna in Petrarch’s Triumphs. Recalling Botting’s definition of ‘gothic’, which he relates to the idea of excess, the traditional canon of ‘beauty’ as outlined by Pozzi could be a valuable tool to measure both the presence and the absence of beauty – its percentage of excess – in Varano’s visionary work. Moreover, physical beauty is based on two standards, exemplified as ‘the long canon’ and ‘the short canon’, as mentioned before. The former is related to the body as a whole, in all its parts, colours, shapes and proportions, while the latter focuses on the face and mainly emphasises the colours. These two canons will be the guidelines for my analysis as far as the body is concerned. The constellation of words from Varano’s Visioni to be examined within this cluster necessarily includes the word ‘corpo’ and its plural ‘corpi’, together with its cognates that are all to be found in the text, namely: ‘cadavere’, ‘cadaveri’, ‘frale’, ‘salma’, ‘salme’, and, as a sineddoche, the word ‘ossa’. In opposition to the materiality of the body, I will also consider the word ‘alma’ and its plural ‘alme’, and the Roman concept of ‘larva’ and its plural ‘larve’. These words, in turn, will require the analysis of other terms, which will be examined accordingly.

(B) My work employs both historical and etymological dictionaries, and it makes use of repertoires and lexicons that could have been used by authors in their own times. Among the main sources, my examination considers the fourth edition of the Vocabolario degli Academici della Crusca or Dictionary of the Accademici della Crusca (1729-38), available online, whose historical innovation lies in its methodology, unprecedented in the Italian lexicographical tradition.[3] Moreover, I employ the Grande dizionario della lingua italiana (GDLI), published from 1961 onwards, whose final volume was issued in 2002 and which is considered the largest and most important historical dictionary of the Italian language.[4] The quality of this work makes it a reference point for any scholar of Italian language and literature. The GDLI represents an excellent tool for properly understanding the cultural implications of language in its historical evolution. Moreover, it provides a large wealth of examples from the Italian literary tradition, from the fourteenth century to the early twentieth century. GDLI also organises meanings and acceptations of words by using ‘currency’ as a guiding principle. As for the etymological derivation, an indispensable source is constituted by Cortelazzo and Zolli’s Italian etymological dictionary, the DELI.[5] By so doing, my analysis attempts to provide a quantifiable, evidence-based, and archaeological outline of the presence of sepulchral themes in the Italian literary corpus. During the progress of my study, key terms will be discussed in their historical construction, forming semantic ‘clouds’ through which phenomena of thematical pervasiveness can be investigated. Such research will not be disjointed, of course, from literary-historical and, more broadly, historical contextualisation, as outlined above.

(C) My third theoretical approach relies on Harold Bloom’s idea that every new composition is an adoption, manipulation, alteration or assimilation from literary predecessors in certain aspects of the content, literary style or form of a certain work.[6] This is the basis of the concept of ‘literary influence’. However, the study of ‘influence’ has been gradually replaced by the concept of ‘reception’, centering instead on reaction, opinion, orientation and critique, thus shifting from being author-centric to reader-centric.[7] By re-appropriating Jauss’s paradigm of reception, which refers to a historical application of the reader response theory, I will read some of my primary sources (the latest of which will probably be Ugo Foscolo’s Ultime lettere di Jacopo Ortis) as a reader’s response to older texts (in this case those by Varano and Fiorentino), while at the same time charting the circulation and popularity of the latter across the decades in question.[8] In this way, I will analyse sepulchral literature as the combined product of the reader’s own horizon of expectations and the actual reception (confirmations, disappointments, refutations and reformulations) of these expectations. Therefore, if interpreted through this theoretical lens, sepulchral literary stream acquires the status of a cultural product revealing the attitudes with which the Italian writers of the early nineteenth century perceived and interpreted previous literary models in their own historical age. My semantic and lexicographical analysis will support the study of the linguistic and aesthetic expectations of the readers, which change over the course of the time together with the biopolitical organisation of the dead and the institutionalisation of cemeteries in the Italian context.

Background

Scholarship has traditionally considered sepulchral Italian poetry as:

a) a minor stream of eighteenth-century literary taste;

b) an Italian appendix deriving from a broader sepulchral and Ossianic fashion which originated in the British context;

c) an isolated presence within the historical framework of Italy’s literary tradition, marginally influencing works such as Foscolo’s Dei Sepolcri and Leopardi’s ‘canzoni sepolcrali’.

Such marginalisation was also part of the broader, ideological refusal of ‘excess’ – and, therefore, of the Gothic – characterising Italian culture since the early nineteenth-century, whose biases were incorporated by Italian Studies in the very vocabulary of the discipline.[9] As Fabio Camilletti maintains, the alleged ‘absence’ of an Italian Gothic tradition stems from a long-lasting cultural prejudice against the ‘horror’ as a form of aesthetic excess.[10] In other words, representations of death can be accepted in Italian literature only if they do not involve their aspect as abjection, namely – to borrow Foucault’s terms from Naissance de la clinique – the macabre and the morbid.[11] This explains the presence in Italian cultural imagery of typical representations of a monumental and titanic but always measured and decorous death, as portrayed in Neoclassical statuary.

Given this general context, my thesis pivots on three main arguments:

a) Italian sepulchral poetry is rooted in eighteenth-century Italian literature;

b) although influenced by foreign (i.e. Anglo-Saxon) models, it also possessed autochthonous origins;

c) it influenced later literary experiences in a more intense and ramified way than commonly acknowledged.

The main primary source

I take as my starting point the Visioni sacre e morali, completed in 1766 by Alfonso Varano, a fairly successful author in his own age, but largely neglected in later decades (although he would be one of Leopardi’s models in composing Appressamento della morte). Varano heralds several of the features characterising sepulchral-related literature in late eighteenth-century Italy, such as a strong relationship with literary tradition (in particular Dante) and a substantial independence from non-Italian models, contrary to one of the main assumptions of scholarship working on Italian ‘graveyard poetry’. Visioni sacre e morali, is a collection of twelve lyrical compositions, correlated one with another, which were composed between 1749 and 1766. I chose this work primarily as it demonstrates my idea about Italian sepulchral literature as an autochthonous phenomenon, not uniquely derived from Anglo-Saxon sources. This hypothesis, which gives a new dignity and a new important role to Varano’s work, has already been maintained by several scholars, including Binni, Cerruti, Mazziotti and Verzini, but has never been fully developed or taken as a starting point for a critical reappreciation of the sepulchral theme in the Italian canon.[12] The role of Visioni sacre e morali as a source for later literary works has been recognised by Binni, Verzini, Spaggiari, and Penso who have remarked how excerpts from Varano’s work are included by Leopardi in his Crestomazia italiana[13] and have stressed his influence on Foscolo’s and Monti’s poetry.[14] Furthermore, the novelty of Varano’s poetry, re-negotiating Catholic ethics through the re-appropriation of the medieval genre of visio, forms an important source for Leopardi in composing his Appressamento della morte, one of the works reintroducing Dante’s terza rima as a model for nineteenth-century religious-inspired poetry.[15] Several scholars have discussed both Varano’s fortune in his own time, as is confirmed by the numerous editions of Visioni in the late eighteenth century, and his decline in later decades, which confined him to the ‘minor’ authors of the Italian eighteenth century’.[16]

My corpus also includes other texts belonging to the genre of Italian graveyard poetry. Among these, I will analyse excerpts from Salomone Fiorentino’s highly popular Elegie in morte di Laura sua moglie. Like Varano’s work, selections from Fiorentino’s Elegie are included in Leopardi’s Crestomazia. Moreover, the closeness, in thematic terms, between Fiorentino’s work and Varano’s Visione X invites one to read them in parallel. Indeed, Fiorentino seems to be a good example of an author who has been influenced by Varano, contributing to the popularisation of visio as a genre throughout the late eighteenth century.

Simona Di Martino, PhD student in Italian Studies, University of Warwick

[1] Fred Botting, Gothic (London: Routledge, 1996).

[2] The notion of ‘Gothic’ is a recent import in Italian Studies. As Stefano Lazzarin has demonstrated, the critical debate on Italian fantasy literature has been largely monopolized by the notion of the ‘fantastic’ coined by Tzvetan Todorov, and only in recent times have scholars tried to expand their corpus through an intentionally broad understanding of the ‘Gothic’ (Stefano Lazzarin et al. (eds.), Il fantastico italiano: bilancio critico e bibliografia commentata (dal 1980 a oggi) (Florence: Le Monnier, 2016)). These include, from different perspectives: Francesca Billiani and Gigliola Sulis (eds.), The Italian Gothic and Fantastic: Encounters and Rewritings of Narrative Traditions (Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007); Fabrizio Foni, Alla fiera dei mostri: Racconti pulp, orrori e arcane fantasticherie nelle riviste italiane 1899-1932 (Latina: Tunué, 2007); Fabio Camilletti, ‘“Timore” e “terrore” nella polemica classico-romantica: l’Italia e il ripudio del gotico’, Italian Studies, 69.2 (2014), 231–45, p. 244 and Italia lunare. Gli anni Sessanta e l’occulto (Bern: Peter Lang, 2018).

[3] Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca, Quarta edizione 1729-38 (Firenze: presso Domenico Maria Manni).

[4] GDLI: Grande dizionario della lingua italiana, ed. by Salvatore Battaglia (Torino: UTET, 1961-2002). The critical opinion has been expressed in Pietro G. Beltrami and Simone Fornara, ‘Italian Historical Dictionaries: From the Accademia Della Crusca to the Web’, International Journal of Lexicography, 17 (2004), pp. 357–84.

[5] DELI: Dizionario etimologico della lingua italiana, ed. by Manlio Cortelazzo and Paolo Zolli (Bologna: Zanichelli, 1979-1988).

[6] Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973).

[7] Robert C. Holub, Reception theory: a critical introduction (Methuen, 1984); see also: M. A. R. Habib, Modern literary criticism and theory: a history (Wiley-Blackwell, 2008).

[8] Hans Robert Jauss, Toward an Aesthetic of Reception (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982).

[9] Aloisi and Camilletti, ‘Introduction’, in Archaeology of the Unconscious, pp. 1-12, p. 5.

[10] Camilletti, ‘“Timore” e “terrore” nella polemica classico-romantica’; see also Maria Antonietta Frangipani, Motivi del romanzo nero nella narrativa lombarda (Rome: Elia, 1981) pp. 8-9.

[11] Michel Foucault, Naissance de la clinique: une archéologie du regard médical (1963), transl. by A. M. Sheridan Smith, The Birth of the Clinic: an Archaeology of Medical Perception (New York: Vintage Books, 1994).

[12] Walter Binni, Preromanticismo italiano (Napoli: Edizioni Scientifiche italiane, 1947); Marco Cerruti, Storia della civiltà letteraria italiana Vol. V (Turin: UTET, 1992); Anna Maria Mazziotti, ‘Per una rilettura delle “Visioni” di Alfonso Varano’, La Rassegna della Letteratura Italiana, LXXXV (1981), 114–30; Riccardo Verzini, ‘Introduzione’, in Visioni sacre e morali (Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, 2003), pp. 9–37.

[13] Giacomo Leopardi, Crestomazia italiana poetica, cioè scelta di luoghi in verso italiano insigni o per sentimento o per locuzione, raccolti, e distribuiti secondo i tempi degli autori, dal conte Giacomo Leopardi (Milan: Stella, 1828) pp. 284-326; Giacomo Leopardi, Crestomazia italiana. La poesia, ed. by Giuseppe Savoca (Turin: Einaudi, 1968) pp. 234-268.

[14] Walter Binni, ‘Leopardi e la poesia del secondo Settecento’, La Rassegna della Letteratura Italiana, LXVI.3 (1962), 389–435; Walter Binni, ‘L’esperienza leopardiana tra fanciullezza e adolescenza, fra educazione cattolica, attrazioni della Restaurazione e sviluppi storico-personali’, in La protesta di Leopardi (Florence: Sansoni, 1980), pp. 25–36; Verzini, pp. 9-37; William Spaggiari, ‘Monti, Minzoni, Varano: gli esordi poetici’, in Monti nella cultura italiana I, ed. by Gennaro Barbarisi (Milan: Cisalpino, 2005-2006), pp. 27–28; William Spaggiari, Geografie letterarie. Da Dante a Tabucchi (Milan: LED Edizioni Universitarie, 2015) pp. 27-28; Andrea Penso, Un libero di Pindo abitator. Stile e linguaggio poetico del giovane Vincenzo Monti (Rome: Aracne editrice, 2018) pp. 16, 34, 39, 42, 46, 49, 50, 64–70, 91, 95, 104, 108–110, 113, 116, 126, 192, 200, 202, 241, 251.

[15] Giacomo Leopardi, Appressamento della morte, ed. by Christian Genetelli and Sabrina Delcò Toschini (Rome: Antenore, 2002).

[16] See for example: Terenzio Mamiani, ‘Poeti italiani dell’età media ossia scelta e saggi di poesie dai tempi del Boccaccio al cadere del secolo XVIII’, in Parnaso italiano (Paris: Baudrij, 1848); Mario Fubini, ‘Introduzione’, in Lirici del settecento, ed. by Bruno Maier (Verona: Riccardo Ricciardi Editore, 1959) pp. XLVII-LII. Lirici del secolo XVIII con cenni biografici (Milano: Sonzogno, 1877), pp. 69-73; Poesia del Settecento, 2 voll., edited by Carlo Muscetta e Maria Rosa Massei, (Turin: Einaudi, 1967) see vol. II, pp. 1849-1872; Antologia della letteratura italiana, edited by Maurizio Vitale, (Milan: Rizzoli, 1967) see vol. IV Il Settecento e l’Ottocento, pp. 389-394; Poesia italiana del Settecento, edited by Giovanna Gronda, (Milan: Garzanti, 1978) pp. 195-198.

Change Is On Its Way

Marc Olivier (Ulster University): My research mainly focuses on the syntax of Romance languages, with a particular interest for the Middle Ages. My doctoral thesis investigates the evolution of clitic placement in a corpus of French legal texts dating from the twelfth century to the nineteenth century. I analyse the development of French and compare it with the syntactic evolution of other Romance languages.

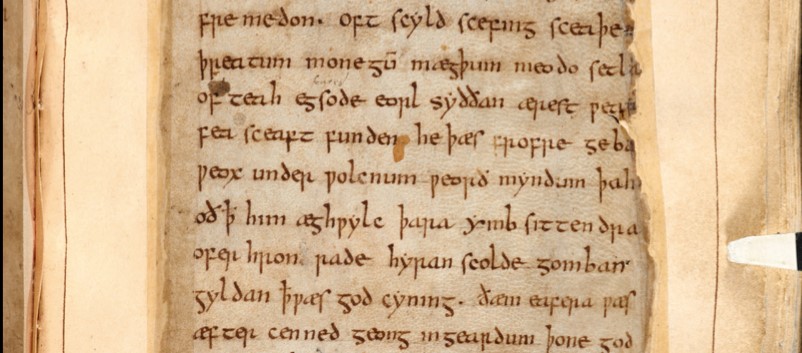

Ne hyrde ic cymlicor ceol gegyrwan hildewæpnum ond heaðowædum billum ond byrnum (Beowulf, 38-40). Unless you are familiar with the English language as it was written at the turn of the second millennium, this article probably starts with some gibberish to you. Beowulf, probably the most-known poem that was ever written in Old English, has become a window to the past. If one could travel back in time and ask the poet what language he wrote his verses in, he would probably answer with a shrug, “English”; and it would be absurd for him to say, “Old English”. Jumping back to 2020: our everyday speech is the same as our parents’ (although one might use some fashionable expressions that belong to their age category), and we also are able to communicate with our grandparents without having to Google translate every phone call they give us. Similarly, they would communicate with their parents and their grandparents, for they all spoke the same language, and so on. Should this actually be true, we would go back in time to our poet speaking a fairly identical English to the one I am using here. The solution to this issue lies in every speaker: new generations of speakers constantly bring in new alterations to the language, sometimes almost imperceptibly. During the last thousand years, it never happened that one day, English speakers went to bed uttering sentences like “ne hyrde ic cymlicor…” and woke up the next day speaking “Modern” English. In a thousand years’ time, 2020 English will probably be qualified as ancient too.

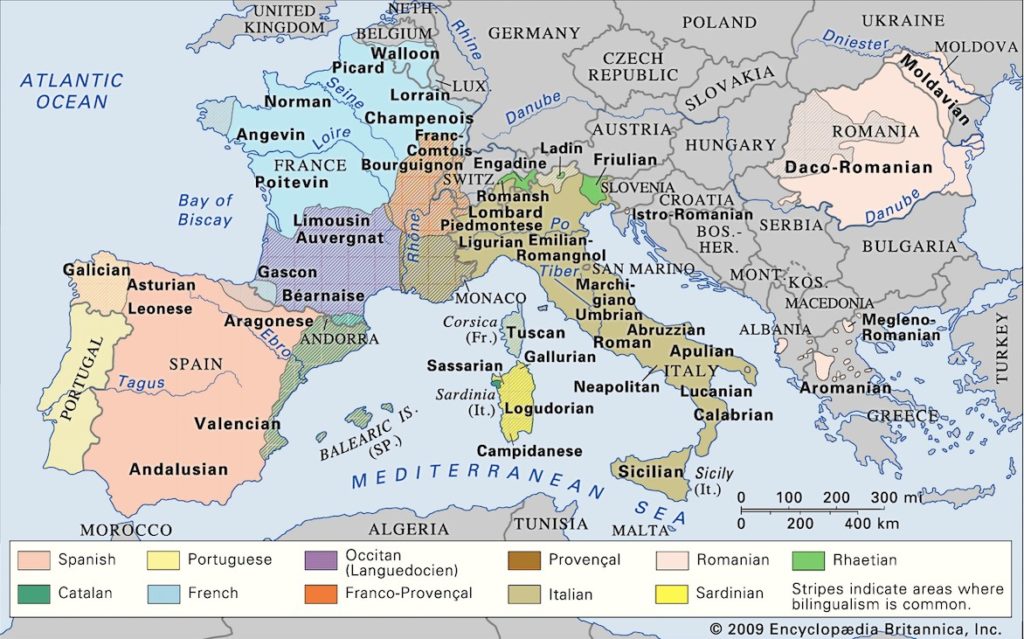

There is a subfield in linguistics that is dedicated to the study of language change: diachrony. My research focuses on Romance languages: at the fall of the Roman Empire, Latin was spoken in a great many places in Europe. Fifteen hundred years later, Latin is not gone: it has slowly evolved into Portuguese, Ladino, Occitan, French, Rumanian, Spanish, Romansh, etc. The Romance family counts many languages and dialects that emerged from Vulgar Latin.

Incidentally, many of them have developed a similar pronominal system, with the use of clitics: le, li, a, la, lo, o, me, mi, te, etc. Clitics are short pronouns that need to be ‘hosted’ by a word that is ‘stronger’, i.e. with full prosodic stress. In the Romance languages that have clitics, the host often is a verb: et veig, achète-le, la voglio, comerlo, etc. There is a quite well-established paradigm with clitics preceding conjugated verbs and following infinitives: this can be attested in Catalan, Italian, Spanish and others. Moreover, languages that follow the aforementioned paradigm have the option to remove the clitic from its infinitival host and place it before the conjugated verb. This can be illustrated in Italian “I can cook it”; posso cucinarlo – lo posso cucinare. However, French behaves otherwise. It allows clitics to precede the infinitive and forbids them from following it; it also lacks the possibility to allow a clitic to climb from its infinitival host to get hosted by a conjugated one.In order to understand why French is different, I have collected sentences with clitics from the earliest period that has available written material, i.e. the 12th century, until the modern pattern is established. Preliminary analysis suggests that Old French obeyed the paradigm and then drifted apart from its sisters. Change does not occur overnight, therefore my thesis covers seven centuries to understand and explain how change takes place, and why the structure of languages evolves.

Marc Olivier, PhD researcher in historical linguistics at Ulster University, Belfast.

Translating Shakespeare into French

Professor Jean-Michel Gouvard reflects on the challenges of translating Shakespeare into French

During the lockdown in France, it has been impossible to buy or borrow a book. So to help pass the time, I reread some of Shakespeare’s plays I had on my bookshelf. I do not work on Shakespeare or on Elizabethan theatre, but I really think he is one of the greatest writers of all time, and so thought he would be a pleasant companion for fleeing far away from the pandemic. Having said that, I also perceived an analogy between the changing and unstable world of the 16th century and the strange times we are going through now. Anyway, delighted as I was by many plays, scenes and lines, and wanting to share my love for Shakespeare with my (French) family, I tried to translate the Jaques’ famous “All the world’s a stage” speech from As you like it (2.7., 139–166). I soon discovered that, while reading Shakespeare had allowed me to escape Covid-19, translating him was a much more challenging proposition.

Let’s begin with the first sentence, “All the world’s a stage / And all men and women merely players”. I cannot render “all the world” by “tout le monde”, because “tout le monde” in French means “everybody”. A better translation might be “le monde entier” (“the entire world”). But, by doing this, I slow down the rhythm of the original: with Shakespeare’s sentence, we have only monosyllables, a verb reduced to a single consonant, “’s”, and a striking parallelism between the two nouns, “the world”/“a stage”. Perhaps it might be better to put “entier” to one side for now and to say “le monde est une scène/un théâtre” (see below for the translation of “stage”).

By losing the “all”, however, I lose another poetic effect: the parallelism between the two lines, “All the world” and “And all men and women”, which reinforces the shape of the sentence. Moreover, in this second line, “And all men and women merely players”, “all” remains a problem. “Et tous les hommes et femmes simplement des acteurs” would be awful, if not wrong, because in French we have a gender agreement: we must say “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes”. But a translation like “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes simplement des acteurs” still sounds weird. Such a sentence means something like “all men and women (are) just/simply players”, but it does not fit with the specific meaning of “merely”. To render it more effectively into French, we have to use a negative form, “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont que des acteurs”, or, with more emphasis: “tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont rien d’autre que des acteurs”.

Coming now to the word “stage”, this can be translated into French by “scène”, “plateau”, “planches” (“board”), and sometimes by “décor” (“setting”). But what Shakespeare means is that the world is like a theatre, like a play that we, human beings, are all playing – a commonplace in European Renaissance literature. So, the most faithful translation seems to be “le monde (entier) est un théâtre”… but then I encounter a problem because of what the Duke Senior said just before that:

DUKE SENIOR

This wide and universal theatre

Presents more woeful pageants than the scene

Wherein we play in.

JAQUES

All the world’s a stage,

And all men and women merely players.

“Theatre”, “scene”, “pageants”, “(to) play”/“players”, and “stage”: within a few lines Shakespeare uses several more or less synonymous words to refer to the same thing. For “theatre” in “This wide and universal theatre”, I cannot think of a better word in French for this than “théâtre”, the same word I used to translate “stage” in “the world’s a stage”. Perhaps, then, in order to avoid the repetition or the elision of what appear to be different meanings, instead of “le monde (entier) est un théâtre”, I have to say “le monde (entier) est une scène” or “un décor” (“a setting”) or, why not, “une comédie” (“a comedy”). It is less faithful, but I can then avoid repeating a word that is not in the original.

Regarding the lexicon, I encountered some other problems. “Woeful”, a very Shakespearean word, could be translated by “triste” (“sad”) but also by “malheureux” (“sad”, “wretched”), “affligeant” (“distressing”, “grieving”) or “navrant” (“distressing”, “heartbreaking”), and I wonder if “tristes spectacles” is strong enough to render “woeful pageants”? Moreover, the French noun “acteurs” I used until now does not express the “old-fashioned” style we have in “players”. In France, during the Shakespearian period, we used the word “comédien” to refer to an actor; according to the Trésor de la langue française, “acteur” doesn’t appear with the meaning it has today prior to the 17th century (http://atilf.atilf.fr/). It might therefore be better to say “ne sont que des comédiens” instead of “ne sont que des acteurs”.

In the end, the whole section could be translated more or less faithfully by:

LE DUC: Cet immense théâtre universel offre plus de tristes spectacles que les planches sur lesquelles nous jouons.

JAQUES: Le monde entier est une scène, et tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont (rien d’autre) que des comédiens.

If we want to use “comédie” instead of “scène” (although Shakespeare said “stage” and not “comedy”), Jaques’ part could be rendered: “Le monde entier est une comédie, et tous les hommes et toutes les femmes ne sont (rien d’autre) que des histrions.” This would avoid the repetition of “comédie/comédiens”: “histrion” is also an old French word, like “comédien”, that refers to a bad actor who exaggerates his performance (we can see this meaning in the English adjective “histrionic”.)

And you might ask: what of the poetry? And you would not be wrong to do so. This is what I asked myself too: by rendering Shakespeare’s text in simple prose, we miss something. I recommence my translation and try to put it in alexandrines, the “great French verse”, with its twelve syllables and its caesura after the sixth. In the end, I come up with the following lines:

LE DUC

Ce si vaste univers, cet immense théâtre,

Offre de plus navrants spectacles que les planches

Sur lesquelles nous jouons.

JAQUES

Le monde est une scène,

Hommes et femmes, tous ne sont que des histrions.

It is not a word-for-word translation, but we have now the rhythm of the alexandrine, “tatatatatata-stop-tatatatatata”, parallelisms (although they are not those of the original), and sentences with much expressive power. That is the version I prefer, although I really do not know if it sounds good or bad, or not too bad but not too good for English ears. But there is one thing I am sure of, it is that translation is indeed a very good hobby for lockdown times.

Professor Jean-Michel Gouvard, Université de Bordeaux Montaigne, France

Lorena Wolffer’s ‘Evidencias’. Objects as Testimonies

Natalia Stengel Peña is a Mexican sociologist with an MA in Modern and Contemporary Art. After researching topics such as human trafficking and feminicides, she is trying to fight against gender violence from a perspective that merges art and activism. Stengel is a PhD researcher in Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at King’s College London. Her research project explores the rhizomatic effect of Mexican feminist artivism and how it may help to stop gender violence in Mexico. For her research, she is analysing artwork by Lorena Wolffer, Cerrucha, Teresa Margolles, Adriana Calatayud, Juana López and Elina Chauvet.

In Mexico, 66.1% of women have suffered some form of violence (INEGI, 2016). The high percentages of violence against women cannot be attributed to a lack of legal framework or proper mechanisms. As of 2007, Mexico has one of the best laws in the world to protect women: the Ley General de Acceso de las Mujeres a una Vida Libre de Violencia [General Law for Women to Access a Life Free of Violence]. It was a substantial feminist triumph as many of the feminists were involved in the project). It defines violence taking into account international treaties such as CEDAW, and it also settles the mechanisms to guarantee safety for women. Therefore, it could be argued that the problem resides in weak enforcement of the law and a lack of access to justice for victims. With this in mind, the Mexican artivist Lorena Wolffer (Mexico City, 1971) proposed a platform to deal with violence in an alternative way.

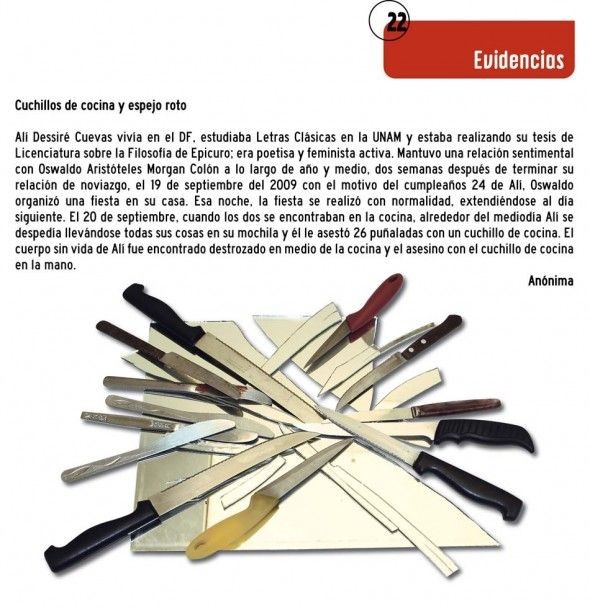

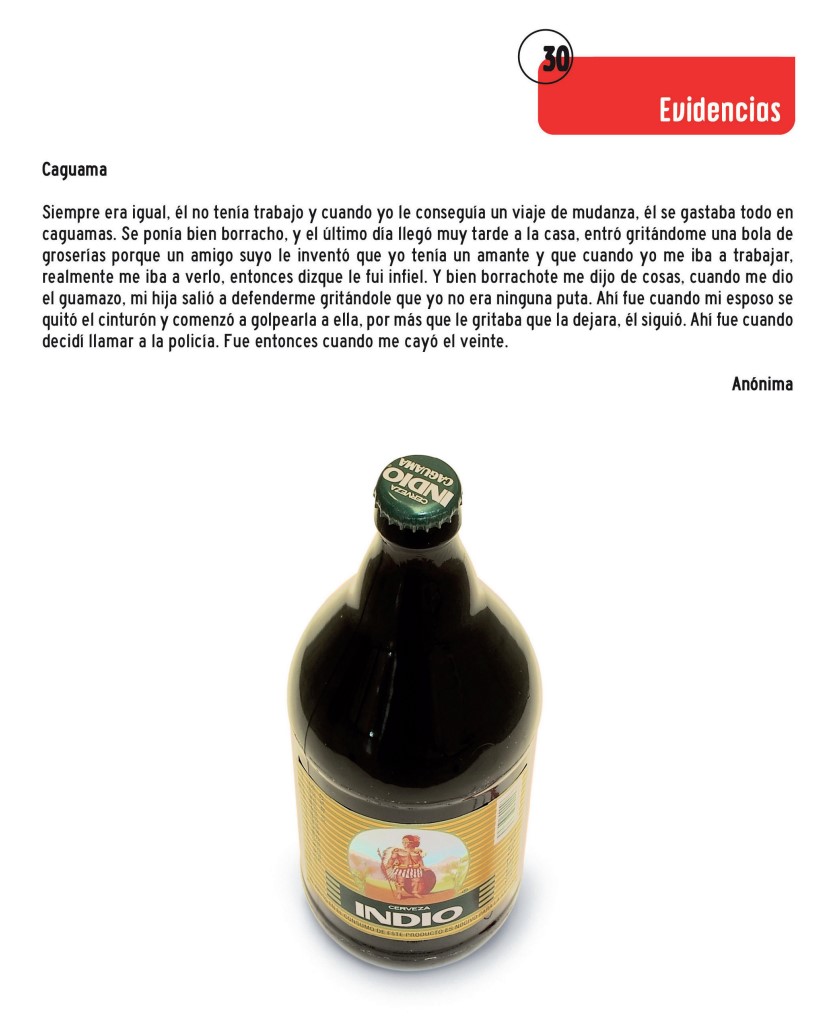

Evidencias [Evidences] (2010-2016) was an installation exhibited in different cities of Mexico that offered a new format to denounce and speak about violence. Lorena Wolffer coordinated the artistic installation, but she was not really in charge. She called for women to donate the objects used to harm them accompanied by a testimony; women arrived at the museum and placed the object how and where they liked. By the time of her last exhibition, Wolffer had 237 objects each one of them revealing a problem that may clarify why violence against women in Mexico persists.

Wolffer exhibited the installation in several Mexican States: Mexico City, Querétaro, Baja California and Jalisco; that way, she was able to reach a bigger audience. However, Wolffer’s objective public was not the spectators but the women donating the pieces of evidence of violence. Though Wolffer has expressed her refusal of being categorised as an artivist since she wants to modify the culture outside the artistic institutions; her cultural intervention projects have some similarities with what artivism looks for: creating a platform for those living in liminality (the margins of the system). Consequently, Evidencias was created for women denouncing, and it is their reaction during the donation what concerned Wolffer. She observed how, by sharing their testimonies and meeting other women who suffered from similar crimes, it was cathartic and promoted a form of sisterhood as a pact among equal women.

In conclusion, Evidencias provides some answers to why the mechanisms available to stop gender violence in Mexico have not been efficient. The exhibition questioned the idea of the family as a strong institution that protects women as most of the testimonies accused the partners or parents as the main perpetrators. Those who did denounce the crimes to the police also testified that it was inefficient and never led them to justice. Though Evidencias did not lead the victims to access justice, it gave them agency when promoting for the victims to take control of what happened to them.

Natalia Stengel Peña, PhD student, Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at King’s College London

WORKS CITED

INEGI, ENDIREH (Mexico City: INEGI, 2016).

México, Ley General de Acceso de las Mujeres a una Vida Libre de Violencia 2007, <http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGAMVLV_130418.pdf>

Museo Malba, Lorena Wolffer — Entrevista con María Laura Rosa, online video recording, YouTube, 2 August 2018 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QXpFZs2qMgM> [accessed 28 May 2019]

Stories from the Exile Archives: Paul Bondy in Internment

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of the mass internment of refugees from Nazi Germany by the British government in May and June 1940, archivist Clare George will highlight over the next few weeks some of the stories of internment from the IMLR’s exile archives.

At the beginning of the Second World War, all Germans and Austrians in the UK were required to attend so-called enemy alien tribunals to determine the security risk they were thought to pose. The tribunals classified the 73,000 who attended into three categories, A to C, depending on the perceived level of their trustworthiness and loyalty to the UK. Fewer than 600 were classed as Category A, those posing a high potential security risk, who were then interned immediately. The majority, around 55,000, were classed as Category C, presenting no security risk; roughly the same number were also recognised officially by the tribunals as refugees from Nazi oppression.

During the spring of 1940, a press campaign against the refugees led by papers such as the Sunday Express and Daily Telegraph began to stir up public fears of foreigners as spies and fifth columnists. With Britain’s position in the war deteriorating and the imminent threat of a German invasion, popular support for the policy of mass internment grew. Under pressure from the military authorities, the government began the wholesale internment of nearly 30,000 Germans and Austrians, starting with Category B men and women in May 1940 and Category C men from 22 June.

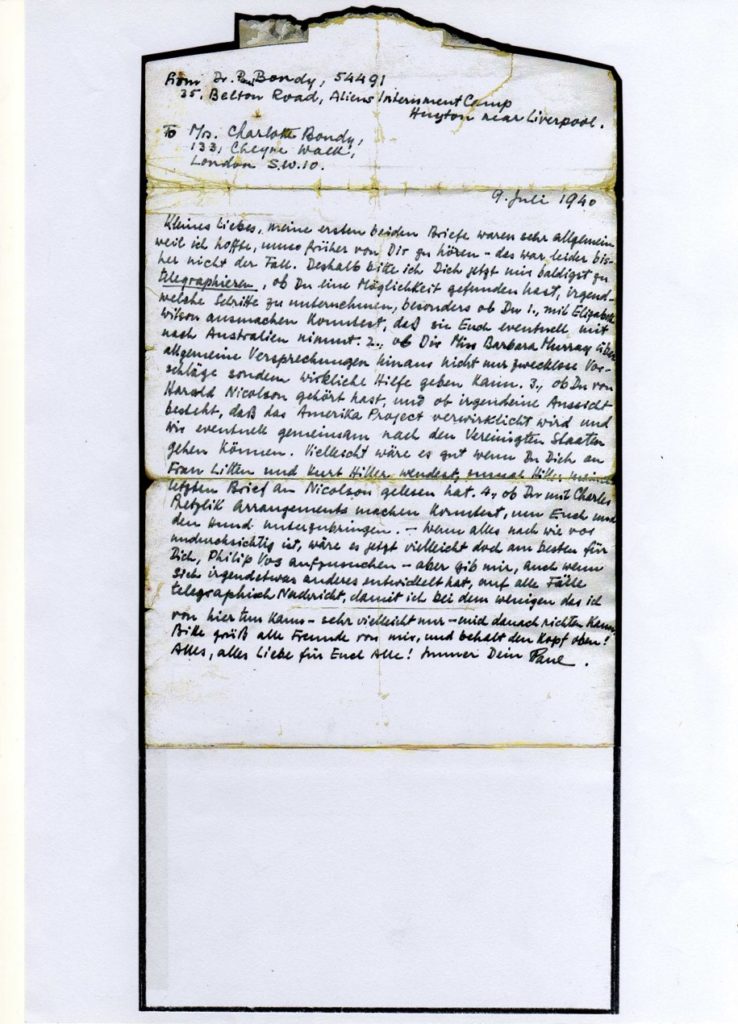

One of the latter group was Paul Bondy, a Jewish aluminium exports manager and trade unionist from Germany. Bondy came to the UK in 1935, followed by his non-Jewish girlfriend Charlotte Schmidt in 1936, to evade the Gestapo. Bondy had been involved in the anti-Nazi underground movement in Bremen, and both Bondy and Schmidt had been arrested and imprisoned in 1935 for contravening the Nuremberg Race Law. Soon after their arrival in the UK they were married, and their daughter, Jo Bondy, was born in 1937.

In the UK Bondy initially managed to find temporary work through his business contacts, but at the start of the war he lost his job, and the family went through several years of severe economic hardship. At his tribunal in October 1939 he was recognised as a Category ‘C’ refugee from Nazi oppression, but eight months later, on 26 June 1940, he was arrested and taken to Chelsea Police Station.

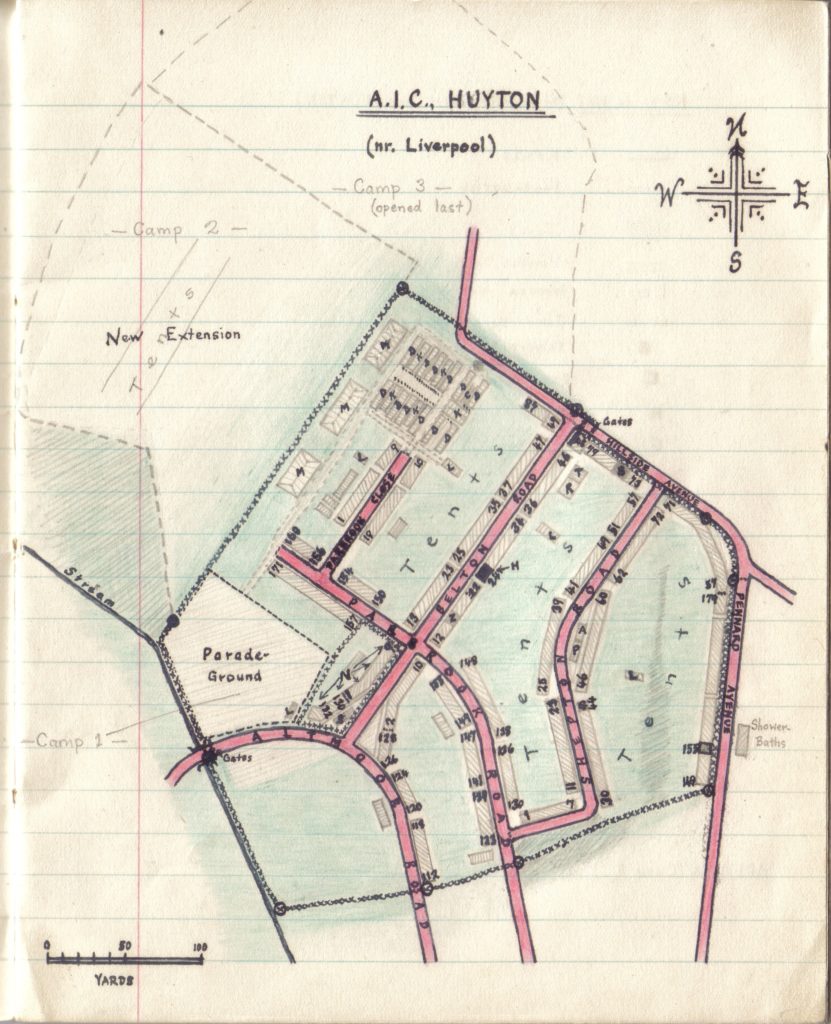

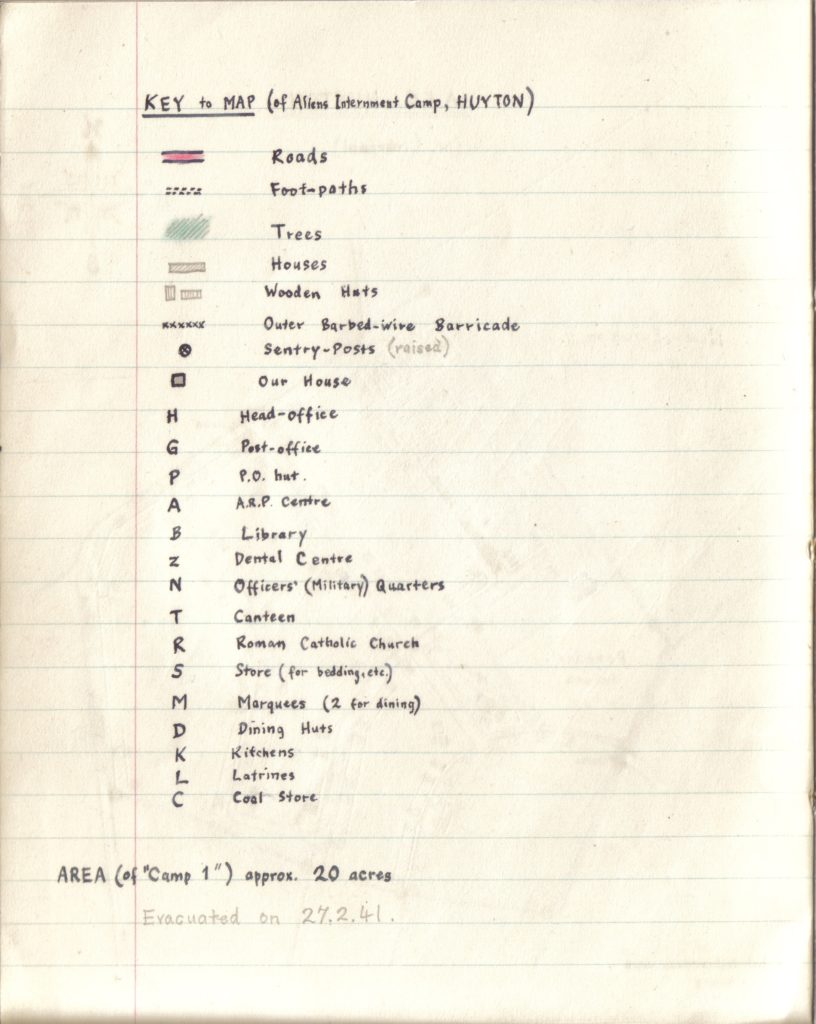

Bondy’s diary records in detail his arrest, detention at Kempton Park, and five-month detention at Huyton Aliens Internment Camp near Liverpool, the largest civilian internment camp on the British mainland. It includes notes on many of his fellow internees, like the Viennese art historian Otto Pächt and the trade unionist Hans Gottfurcht, and details of his and other socialists’ attempts to continue their political work despite their imprisonment. Other records give a fascinating insight into daily life and routine in the camp, including notices of meal and leisure arrangements, a notebook with the names of internees in each hut, and a hand-drawn plan showing the dining areas, the library and the post office. Extensive correspondence between Paul and Charlotte Bondy during his internment is dominated by their discussions about how to secure his release, which did not come until 6 December 1940, despite his application in August based on his status as a recognised opponent of Hitler.

After his return to London, Bondy campaigned for the release of other anti-Nazi activists still interned, including Gottfurcht, Eugen Brehm, Hans Ebeling and Kurt Hiller. He also continued his political work, writing a book detailing the opposition to Hitler in Germany in the 1930s, for which he sadly found no publisher. However, he had no steady paid work and the family lived in poverty, at times effectively homeless and reliant on the kindness of friends and refugee charities, until late 1941, when he finally found steady employment as a radio monitor with British United Press.

The Bondys’ archive, consisting of eight boxes covering the period 1917-1961, was generously added to the IMLR’s exile archives in 2017 by Rosalind Henderson; the donation was kindly arranged by Dr Jennifer Taylor of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, who worked with Jo Bondy on the archive. We are grateful to Dr Taylor for providing the digital images used in this blog post and for her help with interpreting some of the records.

The archive is in the process of being catalogued and a listing will be made available online by the end of 2020. Please note that the reference codes for the images given here are temporary – codes will only be finalised when the catalogue is published online.

Dr Clare George, Archivist (Martin Miller and Hannah Norbert-Miller Trust), Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, IMLR